Axolotls have terrible eyesight. Nocturnal and sensitive to light, the Mexican salamander relies largely on smell and water movement to hunt in the wild. It's ironic, then, that these little critters might hold the key to restoring human vision.

Although modern surgeons have had success with cornea transplants, whole-eye transplants have never restored a patient's vision because of an inability to regenerate the optic nerve. The surgery can be successful, but without a way for the eye to communicate with the brain, any information it might collect goes nowhere.

Axolotls, however, can regenerate almost any part of their body, including their optic nerves, retinas, and parts of their brain.

"This is something that no mammals are able to do," explains Johns Hopkins University student researcher Ted Chor, a senior studying philosophy and neuroscience.

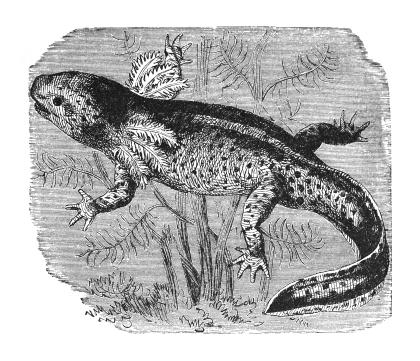

Image caption: An illustration of an axolotl

Image credit: Getty Images

Chor has been interested in regeneration for years, and now, as a recipient of a Provost's Undergraduate Research Award (PURA) and a student researcher in Professor Seth Blackshaw's lab, he is able to learn something truly new. The Blackshaw Lab investigates different questions surrounding the development and regeneration of the central nervous system. Different groups research various aspects of sleep, brain and retina development, and tissue regeneration.

For Chor and postdoc Jared Tangeman, this means studying salamanders. Little is currently known about the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie an axolotl's regenerative abilities.

"We're hoping that by looking at the axolotl, we will be able to uncover new genes," Chor says. "There are obviously many different types of cells in the [eye], so we're trying to see what types of cells the axolotl is regenerating ... to understand how we might be able to take a different approach to stimulating regeneration in mammalian models."

After an eye transplant, axolotls can significantly regenerate their optic nerve in only a month. It's a marvel for Chor to see proof of this under a microscope, even if it raises more questions.

"I remember seeing the optic nerve for the first time," he recalls. "That was so exciting. I had only ever seen pictures of the optic nerve in my neuroscience classes. And this wasn't just any optic nerve, it was a regenerated optic nerve."

Chor received a Provost's Undergraduate Research Award last spring for his work. According to Tangeman, it was a well-deserved honor.

"Ted is a highly skilled scientist who is directly gathering data and producing results," Tangeman says. "He works on everything from experimental design to handling animals, microscopy, data analysis, and more. He is very passionate about the research he does and is frequently bringing forward new insights that he draws from his classes and reading."

After graduating, Chor hopes to attend medical school and become a physician. In the meantime, he's enjoying his time as a researcher, encouraging his classmates to do the same. The Blackshaw Lab is Chor's second lab since starting at Hopkins.

"I'm confident that all students can find a research space that can be an intellectual and scientific home to them," Chor says. "Science often moves at an incremental pace, but every so often it's punctuated by these 'aha' moments of brilliance. It's a moment of just pure awe and wonder when you realize like that, out of the mundanity ... something new arises and you get to be the first person that's ever seen that."

Posted in Science+Technology, Student Life

Tagged undergraduate research, transplants