"Baltimore is sinking, and the sea is rising," Benjamin Zaitchik pronounced on a drizzly, late-summer day in his office at Johns Hopkins University. A professor of Earth and planetary sciences, Zaitchik's brow furrowed as he talked about the state of environmental health research in an era of extreme weather. In a nutshell: It's not good.

"In Baltimore, excessive rainwater pours into an aging infrastructure and underground water-flow channels that are, in many cases, unknown and complicated," he continued. "The soil doesn't stay frozen as long in January, and it rains much more than it snows." These conditions beget floods. And floods beget sewage backups and mold, which beget health problems, home-repair expenses, decreased property values, and stress.

But Baltimore faces additional challenges—many of them representative of those seen in dozens of other midsized industrial cities in the United States, Zaitchik said. Among the challenges: a stagnant population, rising temperatures and heat, and water and air pollution.

Remedies exist for these problems, and Zaitchik and his colleagues want to help devise solutions. They applied for and won a five-year, $25 million grant through the Department of Energy, one for which they teamed up with universities, utility companies, city agencies, and community organizations across the mid-Atlantic region to determine the best path forward. This past March, however, in the fourth year of their work, the federal government pulled back the funding.

Video credit: Aubrey Morse / Johns Hopkins University

Like hundreds of environmental scientists across the United States, Zaitchik received news from the DOE that his grant had been defunded—a brief phone call to say his work no longer aligned with the DOE's mission. The news didn't surprise him, considering the number of grants being canceled around him. "But it enraged me [to see] the disrespect for our work, the loss of opportunity for our students, and, most importantly, the signal that these communities shouldn't have the science they need to thrive," Zaitchik said.

A troubling trend

Zaitchik's project is one of countless federally funded environmental health research projects across the country that have been terminated or scaled back over the past nine months. Federal actions have also reversed a number of climate-related policies and programs created to protect the public from environmental health hazards. According to Columbia University's Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, which tracks such efforts, this includes:

- Putting out of commission (and no longer updating) several long-established data-gathering systems related to extreme weather, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's tracker of billion-dollar disasters

- Issuing an executive order directing the attorney general to prevent states from enforcing policies that address extreme weather, environmental justice, pollution, and related topics

- Rescinding policies that encourage the development of renewable energies like wind and solar

- Exempting coal-fired power plants, chemical manufacturing plants, commercial sterilization facilities using ethylene oxide (a toxin linked to neurological and respiratory symptoms and cancer), and certain iron-ore processing sources from national emission standards for hazardous air pollutants for two years

The administration has also proposed canceling the finding that greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane harm human health—the so-called "endangerment finding" (2009) that enables the Environmental Protection Agency to regulate pollution from power plants, factories, oil and gas companies, cars, and other sources. If this finding were to be reversed—a move that requires approval from Congress—companies would be able to pollute as much as they want, without fear of fines and penalties. A move like this, scientists say, would increase the public's risk of heart and lung disease, as well as other ailments caused by pollutants.

Moreover, these changes disproportionately affect people living in low-income areas, who are more likely to live near major roadways, ports, and factories, Zaitchik said.

The trickle-down effect puts the entire field of environmental science at stake, with a legion of scientists being forced to eliminate post-doctoral positions and reduce graduate student enrollment. Zaitchik said many grants have been canceled simply because they included words or language previously mandated by federal diversity requirements.

"Give me the chance, and I will write those words out of our project descriptions," he said. "But allow us to train the next generation of scientists and continue work already underway."

'A big unknown'

How extreme weather affects urban areas "is currently a big unknown," said Zaitchik, principal investigator of the now-defunded DOE research project known as the Baltimore Social-Environmental Collaborative. Part of the DOE's Urban Integrated Field Lab, the overarching five-year project aimed to determine how extreme weather not just in Baltimore but also in Chicago; Beaumont-Port Arthur, Texas; and Phoenix affects each region's energy, water, and economics sectors. These cities already experience pressing challenges and ensuing costs and health risks from extreme weather, and multidisciplinary teams were put in place to gather data and use what they learn to protect each region's communities.

The teams span multiple institutions and organizations. In Baltimore, for instance, scientists and public health scholars from Johns Hopkins formed partnerships with teams from Morgan State University, Pennsylvania State University, Baltimore Gas and Electric, and the Baltimore City Office of Public Utilities—plus other agencies and community organizations. In other regions, partners ranged from Chicago State University, the University of Illinois–Urbana-Champaign, and Northwestern University to North Carolina A&T University, the University of Texas at Austin, Texas A&M University, Arizona State University, and the University of Arizona, along with an assortment of utility companies, city agencies, and community organizations.

For the projects in all four cities, the DOE defunded 75% of the grant's fourth year and 100% of its fifth year, essentially halting support for the work after investing in and putting in place the equipment, teams of people, and infrastructure to make it happen, Zaitchik said.

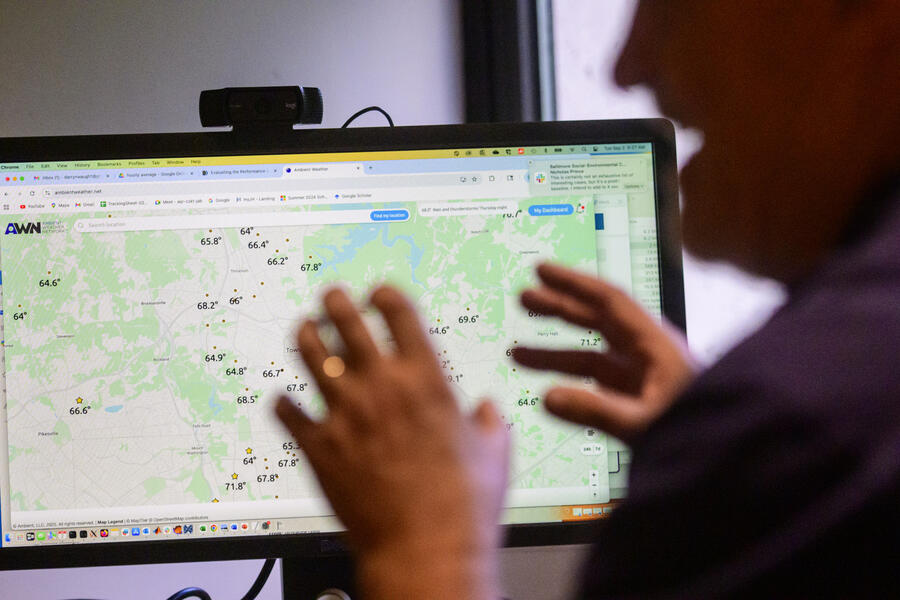

Darryn Waugh, professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Johns Hopkins, works on the project with Zaitchik. He ventured across Baltimore talking to community members and installing and maintaining weather-monitoring stations at churches, recreation centers, schools, and other public places. His goal: collect data on everything from temperature and humidity to wind, precipitation, and pollution—and use it to learn how extreme weather and air quality affect the region's health, economics, and energy supply. Previously, only one weather-monitoring station existed in Baltimore, at the Inner Harbor, and "you cannot tell how heat and rainfall vary across the city from a single station," Waugh said.

Without data to paint a clear picture of what's happening, cities can't prepare for the powerful hurricanes and storms, extensive rainfall and droughts, wildfires, and other weather-related events that are already upon us, Waugh and Zaitchik said. They can't conduct financial analyses to determine the most cost-efficient remedies, and they can't predict the energy demands that are already shifting in what science confirms to be an era of extreme weather.

"Cities and states have budgets and can't fix everything," Zaitchik said. "They have to prioritize, and that can't happen in the dark."

Image caption: Darryn Waugh, Johns Hopkins professor of Earth and planetary sciences, installs a weather monitoring station in a Baltimore neighborhood

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Waugh also serves as principal investigator of a three-year, $1.5 million NASA grant to study air pollution in Baltimore neighborhoods with heavy traffic. These neighborhoods tend to be low-income areas where residents neither own cars nor contribute to the pollution—but nevertheless can suffer the health-related consequences, Waugh said.

Unlike the DOE grant, which was defunded but not completely terminated, "we received a stop-work notice on the NASA grant because it involved an environmental justice angle to help communities of color and communities in need," he explained, referring to the federal government's executive order issued this past January to cease all environmental-justice-related work across the United States, regardless of the specifics.

"We spent years planning the steps, building the systems and teams, and doing the rigorous work it takes to apply for and receive funding, only to have support for our grants up and ended, with no explanation or discussion," Waugh said. "I've worked at Hopkins for 27 years and never seen anything like this."

A series of setbacks

Cancelled grants at Johns Hopkins also include a three-year Environmental Protection Agency award for work to identify the components of biosolids— essentially "sewage sludge"—used to fertilize crops across the country.

"Biosolids are processed human sewage sludge, and they've been contentious forever because of the potential health risks," Keeve Nachman, a professor in environmental health and engineering in the university's Bloomberg School of Public Health, said. "Many of the chemicals in biosolids are both unknown and unregulated, and there are concerns that people being exposed to those chemicals are possibly getting sick."

Also see

Workers who transport biosolids from wastewater treatment plants and spread them on farms experience the most exposure, Nachman said. But given that biosolids are used to fertilize the food we eat, and the food animals eat, and given that runoff from farms can get into our drinking water, most people are exposed at some level, he explained. And the risks and consequences remain unknown.

Carsten Prasse, the grant's principal investigator and an associate professor of environmental health and engineering at JHU's Whiting School of Engineering, worked with Nachman and Sara Lupolt, an assistant scientist in environmental health and engineering, to interview employees of farms that use biosolids. Their biggest finding: Workers face a potentially high level of exposure to toxic chemicals through biosolids, but the EPA doesn't know how much—and hasn't factored workers into their risk assessments and safety guidelines on biosolids. This means, for instance, that farm workers use personal protective equipment inconsistently. And when the machines they use to spread biosolids get clogged with sewage sludge and break down (which happens routinely), they often resort to cleaning the equipment by hand—and risk direct exposure to harmful chemicals.

Prasse and his team, including post-doctoral fellows, doctoral candidates, and other students in his lab, conducted a simulated experiment that involved growing crops on a plot of land and applying biosolids as a fertilizer. Next, they collected samples to determine the chemical makeup and conducted controlled studies to investigate the exposure level to biosolids on crops and workers. Funding for the work was terminated, however, right as Prasse started to identify and analyze the chemicals—in other words, right as his team inched toward their first results.

"We use around 80,000 chemicals in our homes in household products—detergents, cosmetics, personal care products, pharmaceuticals," Prasse said. "All of these things go down the drain, and most aren't really removed in wastewater." In the case of biosolids, he continued, "they contain not just bacteria but everything flushed down the toilet like prescription drugs, pesticides, and industrial chemicals like PFAS" that are known to cause health problems. "All of this sticks to the organic material of biosolids."

The halt in funding is unfortunate for many reasons, Prasse said, including his team's unique ability to identify the array of chemicals—and the quantity of each chemical—in soil and plant samples. In his lab, Prasse uses high-resolution mass spectrometry, a state-of-the-art analytical chemistry technique, to measure the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions with utmost precision and zero in on the elemental composition of compounds. Now, however, his use of the tool is being cut short, owing to the EPA's decision to stop funding the grant.

Both Prasse and Nachman have had other environmental health-related grants descoped or terminated this past year, despite findings that their research can lead to cost-cutting measures and public health safety. "In the case of air pollution, every dollar spent on the Clean Air Act results in a $25 to $30 return on investment in terms of health preventions or in terms of disease avoidance," Nachman said. "I mean, that's stunning. How many programs do we have where we get that kind of return on investment?

"This isn't money thrown away," he continued. "It's money that has high return and tremendous societal benefit."

Zaitchik and Waugh shared similar sentiments, struggling to comprehend the rationale. After all, the grant cancelations and scaled-back funding coincide with a clear uptick in extreme weather, meaning that time is of the essence to gather the data and do the work needed to prepare, they explained.

"It's strange to be rushing head on into these hazards and say, 'Well, we're just going to close our eyes [to extreme weather] and not try to get ready,'" Zaitchik said. "This will only hurt and cost more in the long run."

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged climate change, environmental engineering, environmental health