It's a conundrum: "By 2035, the number of surgeries performed in the United States is expected to double, yet our country already faces a major surgeon shortage," mechanical engineer Axel Krieger said at the Johns Hopkins Data Science and AI Institute's fall symposium. "If we don't do something about it, then 10 years from now, every surgeon will need to perform double the number of surgeries they're already performing.

"This is a crisis," he stressed.

Krieger, a member of the Data Science and AI Institute and an associate professor at JHU's Whiting School of Engineering, is among the many engineers, computer and data scientists, medical researchers, and clinicians at Johns Hopkins leading the charge to ensure that crises like this don't come to fruition. And at DSAI's fall symposium, AI in Daily Life, held Sept. 16 on the Homewood campus and open to the public, he and others presented what they're doing to contend with the surgeon shortage and other pressing health-system challenges.

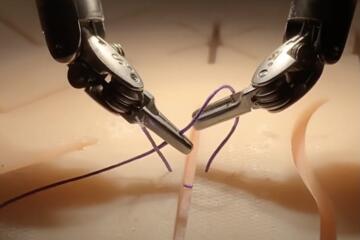

A builder of robots, Krieger and his colleagues are using artificial intelligence to develop "mechanical surgeons" that assist with and perform surgery, first on animals and lifelike artificial patients but eventually, his team anticipates, humans. His Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot, STAR, performed a laparoscopic surgery on a pig in 2022, in what was the world's first autonomous robotic surgery on a live animal. Then, this past July, Krieger's hierarchical surgical robot transformer, SRT-H, performed a lengthy and unprecedented 17-minute segment of a gallbladder removal surgery on a lifelike patient.

By design, the surgery involved spur-of-the-moment hitches in the operating room that mimicked real-life medical emergencies, Krieger said. But SRT-H rose to the challenge, responding flawlessly to voice commands and feedback delivered by humans, correcting itself, and adapting to the twists and turns that surgeons tend to encounter in the OR.

To train SRT-H, the robot watched videos of expert-level surgeons performing their complex trade. "And through that process, SRT-H demonstrated an ability to learn, grow, and self-correct in response to knowledge and information," Krieger said about the federally funded project. "This is a huge step in robotic surgery."

It will take time for robots (with guidance and assistance from humans) to perform surgeries across the country and around the world, but we're on that trajectory, Krieger said.

Image caption: Mathias Unberath, left, and Axel Krieger

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Also presenting at the symposium was Mathias Unberath, director of research, interactive, and embodied AI at the Data Science and AI Institute and an associate professor of computer science at Johns Hopkins with joint appointments in ophthalmology and otolaryngology at the School of Medicine.

"Seeking medical care [in the U.S.] usually comes with a ton of frustration," Unberath told the crowd. "You don't get the care where you need it—in your home—and you have to [make arrangements] to secure child care and travel to your doctor's office, assuming your provider even has an open appointment."

Unberath described the common scenario of waking up with a sore throat—and not knowing whether it was strep, the contagious bacterial infection treated with antibiotics, or something like a seasonal cold that needed to run its course and would likely resolve on its own. "You wouldn't want to spread strep at work or school," he said. "And you'd want to feel better, so you'd need to know."

To help, Unberath and his colleagues worked with Therese Canares, Bus '21 (MBA), a pediatric emergency physician and entrepreneur, to develop a mobile app that serves as a strep-throat screening tool. Users simply upload a photo of their throat. The app then compares the photo to AI images—and determines the likelihood of strep or not in a matter of seconds, while offering guidance on self-care strategies and whether to see a doctor.

Dubbed CurieDx, the app is named after the two-time Nobel Prize-winning Polish-French scientist Marie Curie—a decision made by Canares, who put her clinical work on hold to bring the app to market and add more screening capabilities, say, for rashes and eye infections. Currently, doctors and nurses can use CurieDx in the clinic and via telehealth to help diagnose strep throat, and people everywhere will soon be able to use it at home or on the go, Unberath said.

According to Unberath, AI-based tools like this hold the potential to transform the medical system—in particular, by easing the burden on the health system at a time when chronic illnesses are rising, our population is aging, and physician and nurse shortages are leaving patients without the care they need, he said. Specialists like neurologists, psychiatrists, cardiologists, ophthalmologists, and others are especially in short supply, with patients sometimes waiting more than a year for an appointment, Unberath told the audience.

AI can help, he and others contended. For example, another AI-based device Unberath is developing equips general eye-care providers with the training and tools they need to detect glaucoma, a progressive condition and a leading cause of blindness. Typically, ophthalmologists who specialize in glaucoma make the diagnosis, but securing an appointment often involves a long wait time. With this new AI tool, general eye doctors will be able to spot glaucoma, gauge the severity, and start or manage a treatment regimen, while referring patients with fast-progressing or severe conditions to a specialist.

As Unberath and others develop health-related AI tools, countless more scientists and researchers are creating ways for AI to aid real life—and have been doing so for decades, Rama Chellappa, interim director of DSAI, said. "From work and education to the services we rely on in homes, AI has rapidly become a ubiquitous part of our everyday lives," Chellappa said during his opening remarks. "It's everywhere." And for many years already, he said, we've used AI in our cars to navigate from one place to another and in our homes to ask for weather reports. Now we can add generative-AI chatbots to the mix, and the stream of information they can offer on home repairs, parenting dilemmas, pet training—the list goes on.

Image caption: Alexis Daniels of JHU's Center for Educational Outreach gives a lightning talk about bridging the AI literacy gap in schools

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Alongside presentations and a panel discussion on AI's positive impacts on health care, the symposium featured speakers covering the ethical implications of deploying AI to bolster the workforce, sustainable approaches to AI, and a series of lightning talks including machine learning and climate science, autonomous vehicles and smart infrastructure, and bridging the AI literacy gap in schools.

Benjamin Lee, a professor of electrical and systems engineering and computer and information science at the University of Pennsylvania, discussed another side of AI: the huge amounts of energy and water it requires and the challenge of building sustainable data centers. "Since generative AI came along, we've seen massive growth in the electricity needed to power it," Lee said. "There's a lot of uncertainty in projections [of how much energy and water] data centers will use. ... But we're working on sustainable solutions, and our goal is net zero."

John Tasioulas, a professor of ethics and legal philosophy at the University of Oxford, presented a pre-recorded video on a topic that weighs heavily on the public: the potential of AI to displace workers by putting humans out of jobs. "Engagement in work fosters a sense of achievement, which fosters a sense of self-worth," Tasioulas said. "The rise of AI threatens to undermine this"—a scenario that might be met with difficulty, given that "we've been trained for too long to strive [and be productive]," rather than to "enjoy" life.

In closing, Tasioulas asked the audience to contemplate what would happen if we replaced work with pursuits like playing games, cultivating friendships, following our curiosity, learning about the world, and nurturing our health and spirituality. He posed the question: "Does a healthy democratic ethos rely on most citizens working?"

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged artificial intelligence