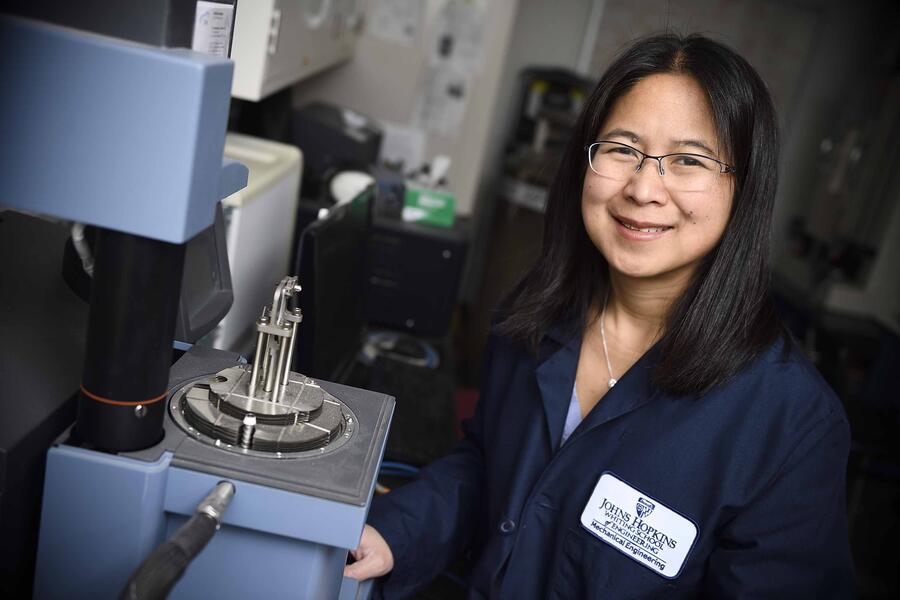

Glaucoma, caused by high pressure within the eye, affects some 2.5 million Americans and is the nation's second leading cause of blindness. Optometrists screen for it during routine eye exams, often with the familiar puff of air against the cornea. But once diagnosed, how does glaucoma progress? That is the question Vicky Nguyen, professor at Johns Hopkins University's Whiting School of Engineering, has spent 15 years trying to answer.

Supported primarily by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Nguyen's team has partnered with Harry Quigley, a professor of ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, to investigate the mechanics behind the disease. They are studying how the eye's tissues respond to pressure changes to identify key factors driving vision loss and enable more effective sight-saving treatments.

"Understanding how the condition progresses is critical to developing better treatments and preserving patients' vision long-term," said Nguyen, who is also co-deputy director of the Hopkins Extreme Materials Institute. "Millions of Americans lose their sight each year to glaucoma, and research funding is essential for helping us find effective ways to change that."

Even with treatment, about 15% of people with glaucoma continue to experience some vision loss, and about 5% go blind in both eyes. Currently, there are no proven biomarkers that can predict which patients will experience a more rapid progression of the disease, so patients are treated with a one-size-fits-all approach. Nguyen's team is working to change that by studying how strain in the optic nerve of glaucoma patients affects their sight.

Recent studies involved patients starting new glaucoma medications and patients who had surgery to lower their eye pressure. The researchers then measured how the tissues of their optic nerve heads (the place where the optic nerves exit the eye) responded to these pressure changes.

So far, Nguyen's team has found that strain within the optic nerves predicts the stages of vision loss in patients with mild, moderate, and severe cases of glaucoma. Their study also demonstrated that these strain measurements can predict how much the structure within the optic nerve head changes a year or more after pressure-lowering treatment.

Lowering eye pressure halts the progression of glaucoma damage for many patients; however, this approach may only provide short-term relief or prove ineffective for others. With support from the NIH, Nguyen's team is monitoring patients who have received this surgery to see who improves or worsens, aiming to clarify whether invasive treatment is truly necessary or beneficial to some patients.

"We will monitor patients in our study for the next four years and repeat these measurements every six months," Nguyen said. "Understanding strain as a predictor of vision worsening will allow us to more effectively screen patients with bad strains for additional treatment or more frequent monitoring, and we can develop new therapies that either stiffen or soften the tissues to slow or halt progression."

Nguyen and her team are not solely focused on identifying which patients using medications face a higher risk of their disease worsening. They are also studying how patients respond to surgical intervention over a long-term period. Their findings related to glaucoma could have implications for other kinds of vision loss caused by intraocular pressure, including the common affliction of myopia—nearsightedness.

"We have learned a lot, but we need more time to find answers," Nguyen said. "NIH support has been crucial and without it, we would have to scale back or stop our patient testing entirely—jeopardizing both the study and the progress patients have made in patient care."

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged mechanical engineering, nih funding