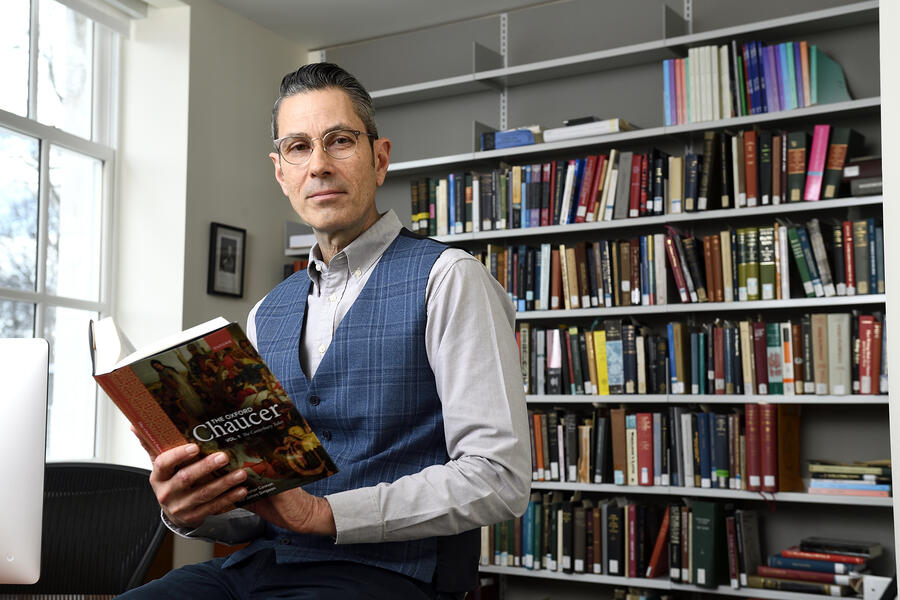

One of the most exciting moments in a professor's life must be unpacking the first print copies of their latest book. As the author of four works, Christopher Cannon, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of English and Classics at Johns Hopkins University, knows this feeling well.

But when recently opening the box from Oxford University Press containing his fifth book, he was both proud of his achievement and daunted by the size of his literary offering. "It was bigger than I imagined," Cannon says. "The weight shows up on the invoice, and if I remember correctly, it's something like five pounds."

The hefty work in question is his two-volume The Oxford Chaucer, released Dec. 17 as the first critical edition of all of Geoffrey Chaucer's works since the 1980s and the only one currently in print. Co-edited with Harvard English professor James Simpson, its more than 1,500 pages offer one-stop shopping for anyone wanting to read and understand the 14th century "father of English poetry," from undergrads to advanced scholars.

Work began on the project a dozen years ago after Oxford University Press, unable to secure digital rights to a competitor's out-of-print version of Chaucer's complete works, tapped Cannon to create one anew. Mindful of the enormity of the task, Cannon partnered with Simpson, a fellow medievalist he met when they both taught at the University of Cambridge. "He was the ideal collaborator because he is brilliant and works very fast," Cannon says.

Anyone reflecting on their first encounter with Chaucer in lit class will likely remember that a principal challenge to reading and comprehending his works is that they are written in Middle English, an early form of English that looks and sounds different from our modern tongue. "To make this more accessible to students, all the hard words are glossed at the bottom of the page," Cannon says of the new Oxford Chaucer. "There are also historical, contextual, and cultural notes that make our edition as rich an experience as possible for undergraduates."

One of the great mysteries surrounding Chaucer is why he decided to write in English at all, seeing how in his day, French was the language of the nobility and prestige literature. However, literacy in English was on the rise among an emerging merchant class. "One of the chicken and egg questions about Chaucer is whether he chose to write in English because it was newly fashionable or whether he actually created the audience for English literature of this kind," Cannon says.

Another challenge scholars face when editing Chaucer is sorting through an array of texts in different manuscripts, each slightly different from the other, trying to work out what Chaucer actually wrote. There were no printing presses in England until almost a century after Chaucer's death, so every copy of his poetry and prose had to be handwritten by a scribe. "These manuscripts vary so much because none survive that were written in Chaucer's lifetime," Cannon says. The sorting of variants also requires that as in mathematics, editors are obliged to "show your work." The Oxford Chaucer is so big in part because it shows more of that work than any edition of Chaucer has before.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Take his most famous work, The Canterbury Tales, a collection of two dozen stories told by an eclectic group of pilgrims en route from London to Canterbury Cathedral. More than 50 manuscripts of the work exist, but most "aren't useful" Cannon says because they are so full of obvious errors. "The Canterbury Tales is particularly challenging because even the order of the tales can vary in different handwritten copies, and Chaucer did not provide a definitive guide because the tales are unfinished," Cannon says. "It has a beginning and an ending, but also all kinds of gaps in the middle that can't be resolved because of inconsistencies."

Scholars even debate the meter Chaucer used because the manuscript paper trail is so full of bumpy lines. "One of the things that we did that other editions haven't is assume that Chaucer wrote regular meter," or poetry written in a consistent pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables, Cannon says. "We feel a lot of previous editors were wrong to think that Chaucer accepted these faults and so accepted many scribal errors as if they were intentional. In the Oxford Chaucer we edited out these variants."

Readers who take the time to work through the archaic language are rewarded with writing that is complex, entertaining, insightful, and even raunchily funny at times. (Canterbury's bawdy "Miller's Tale," replete with a fart joke, comes to mind.) There is a reason Chaucer's works have never fallen out of favor and have been consistently read and argued over for centuries.

Though he died over 600 years ago, there's a whiff of modernity to his writing. "For one thing, Chaucer tried to understand the human suffering through the difficult position of medieval women," Cannon says. "It's fair to call him a feminist in that he not only was thinking about the ways that women's lives were blighted because they were women but he insisted on counting the costs of such oppression." And in an age of strict social hierarchies, Chaucer was adept at seeing the world from multiple perspectives. He was an early diversity champion, while not of race just yet, but of gender and class. Even his more unsavory characters, such as Canterbury's Pardoner, are not one-dimensional villains. "He's the worst sort of person but Chaucer fleshes him out," Cannon says.

"When I teach Chaucer, I like to say he was profoundly humane because he extended his imagination and sympathy to the great variety of ways we are human," Cannon says.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged classics, english, bloomberg distinguished professors