Who was Gertrude Stein? Should she be remembered as a pioneering writer? An early and insightful collector of modern art? A den mother to a 1920s cohort of creatives—Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Joyce—for whom she coined the term the "Lost Generation"? A woman who made little effort to hide her longtime lesbian relationship decades before the LGTBQ+ rights movement began?

Yes. All of this and more. Free and open to the public, the exhibition Gertrude Stein in Circles: Spheres of Life and Writing is on display in the George Peabody Library's exhibit gallery through March 2, 2025. It aims to capture many aspects of this cultural figure, from her days as a Johns Hopkins medical student though her celebrated Parisian salon and on into her still-evolving posthumous legacy.

"For most people, if they know anything about her, it's a vague sense that she was an eccentric writer and art collector during a revolutionary period of the arts, and a queer forerunner," says exhibit curator Gabrielle Dean, curator of rare books and manuscripts for the Sheridan Libraries and an adjunct faculty member in the Krieger School. "But I am hoping to give people more ways to appreciate her. Maybe most importantly, to understand that she was not some strange, solitary genius but someone whose interests and writing and life events developed in relationship with many others." "Circles" in the title refers to just that: her social, artistic, and writing circles, and her other professional and personal spheres that often connected and overlapped.

The exhibition draws mainly from the vast Robert A. Wilson Collection of Gertrude Stein materials the Sheridan Libraries acquired in 2017. Baltimore-born Wilson, A&S '43, ran a Greenwich Village bookshop for nearly 30 years and was an ardent collector of Stein materials. He amassed her artifacts with the eye of an astute dealer in rare books and the passion of a fanboy. Additional objects are sourced from the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives, the Institute for the History of Medicine of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, and the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

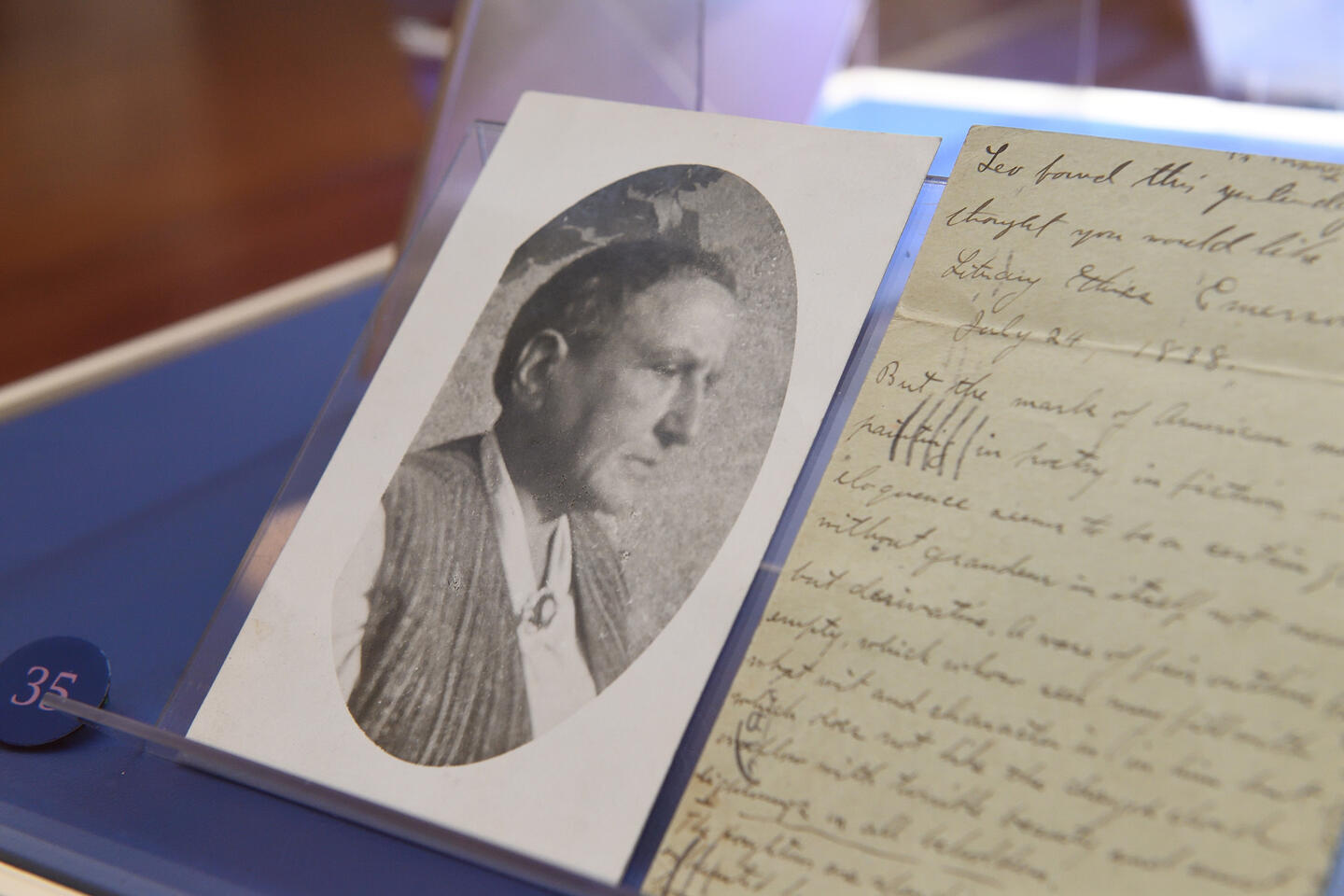

The exhibition is largely arranged chronologically, starting with her first circle in Baltimore. Though Stein was born in Pittsburgh and raised in Oakland, California, she had deep familial roots in Baltimore, where both her parents were born. Stein earned her BA from the all-women Harvard Annex (later known as Radcliffe College) where psychology was a favorite area of study. Then in 1897, she was among the earliest groups of women to be admitted to the 4-year-old Hopkins Medical School and moved in with Baltimore relatives.

Though adept at her studies, Stein quit Hopkins in 1901 just a semester shy of graduation. "She said she was bored," Dean says. "She said she didn't like the clinical rotations, delivering babies in particular. But the evidence suggests there were personal reasons why she didn't continue. Most scholars think it was romantic heartbreak that unsettled what she thought she wanted for her life." Photos show her amid a handful of other women students, their starched white Victorian blouses standing out amongst the coat-clad men. Also on display are some of the textbooks she would have used, as well as the modest, four-page application that got her into Hopkins.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

In 1903, Stein followed her older brother Leo to Paris and never looked back. In a way, her Baltimore circle helped her take up her famous role as linchpin of a Parisian circle of modern artists. In Baltimore, she rubbed shoulders with Claribel Cone and Etta Cone, unmarried art collecting sisters and fellow members of the city's middle class Jewish population. They began buying art from emerging talents in the 1890s, ultimately amassing a large collection of Matisse paintings that now hang in the Baltimore Museum of Art. "The Cone Sisters probably provided a model for the kind of life that [Stein] could imagine for herself," Dean says. Their lives—as educated women traveling around the world and collecting art—were unconventional and independent, and that "must have sounded pretty good" to Stein, Dean adds.

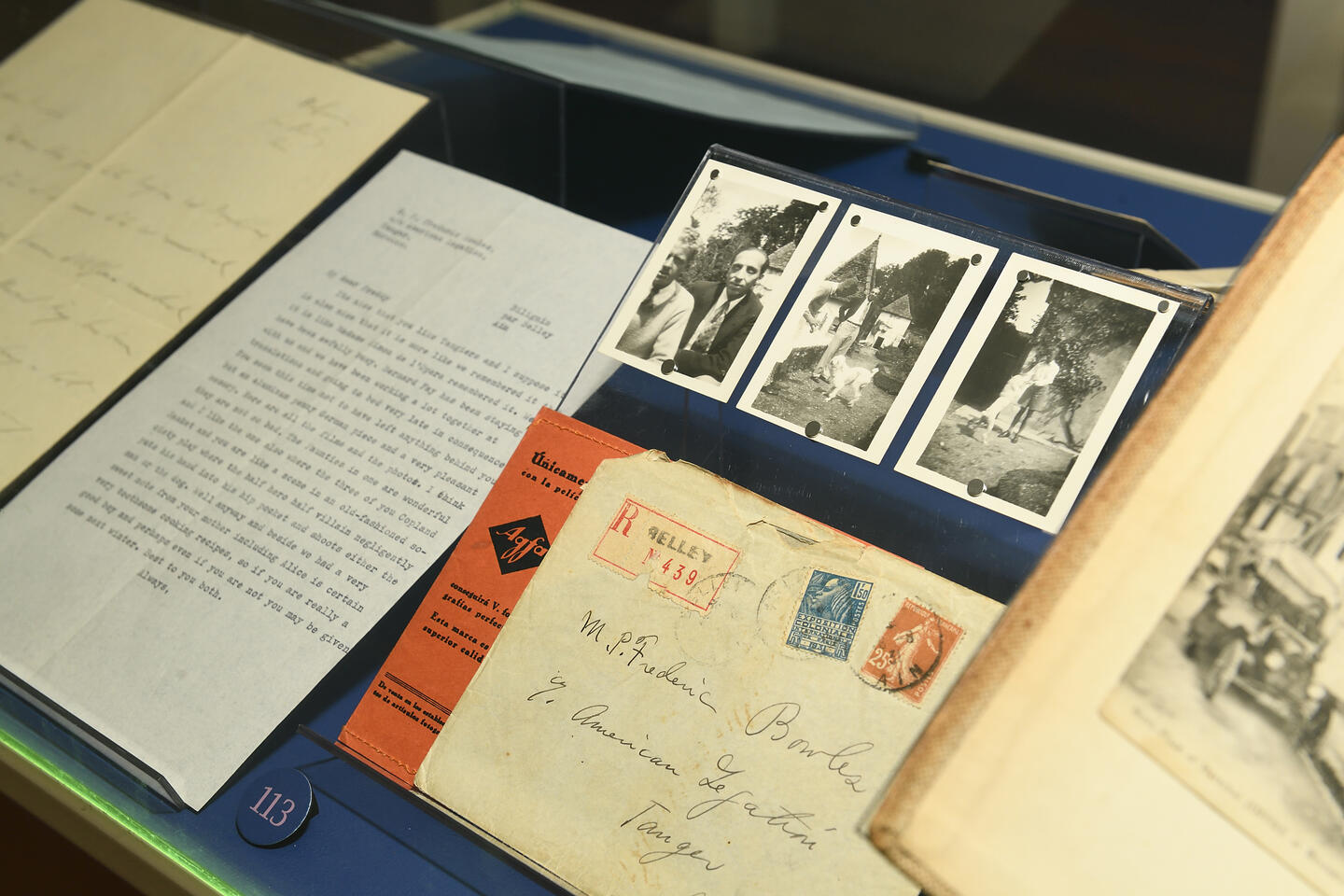

The exhibition includes a letter Stein wrote to Claribel Cone in 1914 announcing the publication of her book of poetry, Tender Buttons. Included in the envelope was a small printed notice from a New York gallery selling the book for $1, along with similar notices about artworks for sale in the same gallery. "One of the little announcements advertises prints by Picasso," Dean says, "which you could get for $15."

Image caption: Curator Gabrielle Dean speaks at the opening celebration for the exhibition. She'll host a conversation with Gertrude Stein scholar and distant cousin Phoebe Stein on Nov. 20 at 6 p.m. EST in the Peabody Library.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Stein started writing in earnest after medical school, adopting a modern style influenced by goings-on in the art world and her studies in psychology. Stream-of-consciousness writing was but one approach she helped pioneer. "She was in search of a language that would convey more immediately what a person's essential qualities were—instead of describing a person, she wanted to capture the subject's character as if it were speaking directly," Dean says. "One of her earliest genres was the word portrait. She was stimulated by the artists around her, especially the artists whose works were hanging on her walls at home, like Cezanne, Matisse, and Picasso. And they were all trying out different visual techniques to convey experience more directly. She herself had her portrait painted by Picasso, which meant she was right there in the room while he tried to portray her in a way that wasn't just about outward appearance. She must have felt what a powerful artistic struggle it was, and similar to her own struggle trying to express a personality in words."

The exhibit includes a copy of that 1905–06 painting, in which Picasso captured Stein with stern intensity (the original hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art). Also on exhibit is her "word portrait" of the Spanish painter that ran in Vanity Fair, rife with repetitions of words and phrases. "Scholars suspect that she wanted to be known as the 'word cubist,' in a way," Dean says. "Picasso was the 'picture cubist'; she would be his counterpart in the medium of language. Each of her word repetitions is like a little touch of paint, and no two are quite the same."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

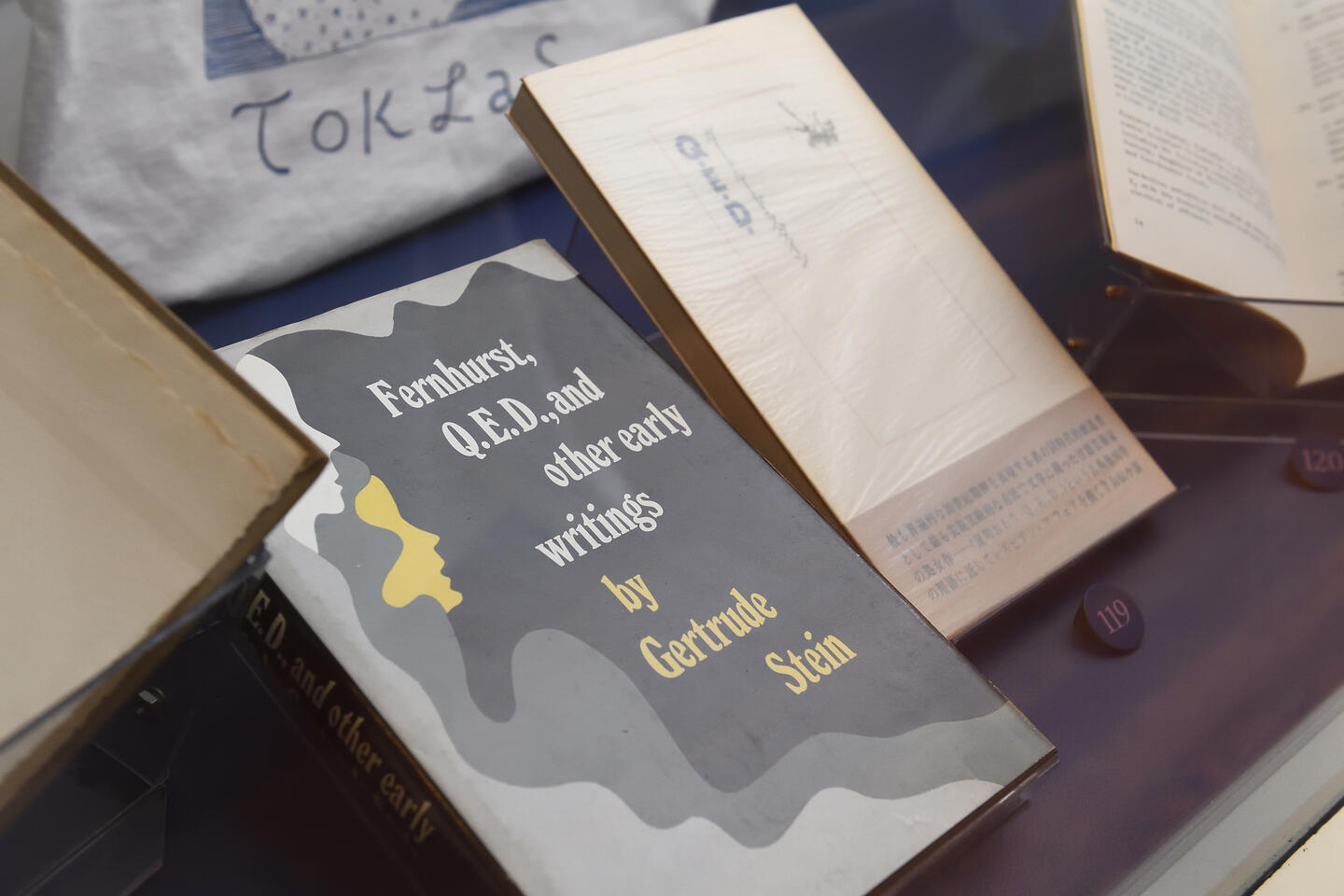

You could say Stein's smallest circle was the one she formed with life-partner Alice B. Toklas, a fellow Jewish American art enthusiast she met in 1907. After years of experimental writing that appealed largely to niche audiences, she wrote The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas in 1933. A first edition of this bestseller is on display, and the gallery guide describes it as "frank, gossipy, and utterly readable." Stein was being playful in titling it as the work of Toklas herself, and she perfectly captured her partner's speaking style.

One of Stein's last works is also on display, 1945's Wars I Have Seen. It describes how she and Toklas drove ambulances to deliver medical supplies to French hospitals in World War I, as well as their experiences in occupied France during the Second World War. It would be hard to find a pair more vulnerable to Nazi persecution: Jewish American lesbians who collected modern art—or "degenerate art," as the Nazis saw it. And yet they survived the war unscathed, their art collection intact. It seems they were protected by a friend who was a ranking member of the collaborationist Vichy government Germany setup in France. The gallery guide says scholars continue to debate this period in Stein's life. They did appear to be "playing both sides" during the conflict, Dean adds, but with the simple enough goal of "trying to survive."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Stein died of cancer in 1946. Toklas outlived her by 21 years and helped keep her memory alive through her own writings, including her 1963 memoir What Is Remembered. After the birth of the LGBTQ+ rights movement in the 1960s, Stein emerged as something of a gay icon. "They didn't dissemble about their relationship and considered themselves married, calling each other Hubby and Wifey," Dean says of Stein and Toklas. "But, obviously in the era in which they lived, their marriage wasn't something they could be explicit about in public." The inseparable pair adopted what could be viewed as a "don't ask, don't tell" approach to their life. This was bold when you consider that in the 1950s and '60s, gay public figures, such as pianist Liberace and Rock Hudson, made a point of keeping public company with members of the opposite sex to avoid raising eyebrows.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Many of Stein's works have since been analyzed for subtle and at times not-so-subtle allusions to homosexuality. On display is one such piece, a short story that ran in Vanity Fair in 1923 called "Miss Furr and Miss Skeene." "She uses the word 'gay' constantly in this piece, so often it's almost funny, and people think this might be the first time that the word 'gay' was used in writing to mean what the word means now," Dean says.

Rounding out the exhibition is a display of Stein items you might not expect to see in such a scholarly context. There is a commercial poster of one of her most famous quotes, "A rose is a rose is a rose," and a range of Stein-emblazoned tchotchkes, including a throw pillow, playing cards, figurines, and even a watch. "What really makes Robert Wilson's collection unique and special is his very meticulous and expansive documentation of her legacy in all kinds of interesting ways," Dean says. "And that includes pop culture items."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Posted in Arts+Culture