- Name

- Jill Rosen

- jrosen@jhu.edu

- Office phone

- 443-997-9906

- Cell phone

- 443-547-8805

If pictures could talk, SHAN Wallace's The Oldest and the Middle would utter, I've got you.

The photo depicts a brother and sister wrapped in each other's arms on North Avenue in Baltimore.

"When I asked to take their photograph, they said, 'Let's show the world how much we love each other,'" says Wallace, the Baltimore-based photographer and mixed-media artist whose work is among nine new contemporary art pieces acquired recently by Johns Hopkins University.

Wallace's photograph is part of a new university commitment to select artists and artwork representing a broad range of perspectives, with many pieces created by local artists of burgeoning acclaim and reflecting some aspect of Baltimore. The effort, which involved an initial investment of $500,000 over two years and includes plans for future acquisitions, is an outgrowth of the university's Diverse Names and Narratives Project. A committee made up of faculty, staff, students, alumni, and trustee representatives selected artwork for purchase and installation.

The pieces will make their way to JHU campuses this spring and be positioned in places where both the public and the Johns Hopkins community can access and enjoy them, with the precise locations to be announced later. Planning is underway for several installation events to celebrate each artist, inviting them to campus to take part in community conversations inspired by their work. Johns Hopkins University President Ron Daniels, members of the art selection committee, and the artists will participate.

"Art is an invaluable conduit for contemplating new possibilities within our society, for reflecting upon our history, and for recognizing our shared humanity," Daniels says. "It's an honor to bring these powerful and thought-provoking pieces to our campuses and to celebrate the breadth of artistic talent across Baltimore, a city Johns Hopkins is deeply proud to call home."

In addition to Wallace, the roster of artists includes painter and printmaker LaToya Hobbs, painters Linling Lu and Ernest Shaw Jr., sculptor Sebastian Martorana, and photographer Elena Volkova. All based in Baltimore, they collectively represent a diverse group of visionary artists working at the forefront of their fields, helping to create a new visual narrative for a city steeped in challenges yet teeming with positivity.

Hobbs explores themes like motherhood and spirituality through her larger-than-life portraits of Black women, while Lu works in the realm of the abstract, painting concentric circles in effervescent colors. Martorana culls pieces from Baltimore's discarded (yet historical) architecture, and Volkova depicts people on thin sheets of metal, reviving a Victorian-era form of photography, tintypes. Shaw, meanwhile, is a portrait painter striving to humanize and shed light on the Black experience.

"When I moved here four years ago, I was blown away by the abundance of artists and their immense motivation to create," says Jessica Bell Brown, the curator and department head of contemporary art at the Baltimore Museum of Art, which owns pieces by Wallace, Volkova, Lu, Shaw, and Hobbs. "Economically, the city has become a reprieve from the exorbitant expenses of L.A. and New York. That factor, combined with the incredible intellectual life and many colleges in Baltimore, has created alchemy."

Daniel Weiss, a humanities professor at the Johns Hopkins Krieger School of Arts and Sciences and former president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, agrees. "Baltimore has attracted artists for a long time," he says. "Artists come from all over to attend MICA, the art school at the center of Baltimore's art scene, and other outstanding universities in the area. Many end up staying because of the city's amazing vitality, its rich history and character, and its affordable studio spaces."

Yet artists attempting to make it internationally can struggle to find options to exhibit locally, instead booking shows in global art meccas like New York, Los Angeles, Mexico City, London, Paris, Seoul, and Tokyo. This is where "Johns Hopkins can make a difference, supporting artists as they grow their careers, while stimulating the local arts ecosystem," says Cara Ober, the editor-in-chief and publisher of the independent art magazine BmoreArt, who curated a portfolio of artists for consideration by the Johns Hopkins committee to help select the chosen pieces.

Ober says she believes the investment will benefit not just artists and those who see their work, but also the larger university. Savvy art collectors buy from flourishing artists who haven't yet achieved wide notoriety, Ober suggests. "Etta and Claribel Cone weren't collecting famous artists at the time," Ober says of the sisters who amassed and bequeathed more than 3,000 art objects—many by Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso—to the BMA. "They were collecting artists they believed in … [and] saw value in, when others did not."

The six artists selected by Johns Hopkins "are all on the cusp of national and international acclaim, exhibiting their work regularly outside of Baltimore and selling pieces to collections across the country," Ober adds.

Here's a look at their practice and work.

SHAN Wallace

A native of East Baltimore, Wallace says her hometown gets a bad rap. "People know Baltimore from the flood of media surrounding the Freddie Gray riots in 2015," she says. "They know it for the gang violence in The Wire." Thus, she strives to document and humanize a place that many only see through the fog of stereotypes.

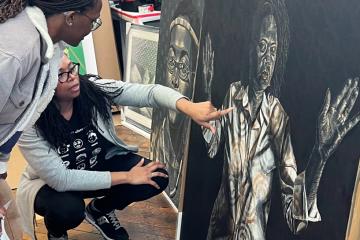

Image caption: SHAN Wallace

Image credit: Nayquan Shuler

As a photographer who studied journalism at Bowie State University, Wallace depicts a different side of her hometown—one that looks beyond crime and poverty to reveal the human side of individual residents. "Plenty of images exist of Black people in defiance or resistance of something, but I focus on the quiet moments of everyday life," Wallace says. Even still, her work doesn't shy away from social issues like inequity and poverty. For instance, in a photo series for The Washington Post, Wallace presents Baltimore residents waiting for the bus—a seemingly mundane act that "raises questions about race and socioeconomics in our city," she says. Likewise, her photo series of Lexington Market documents the bustling gathering space known not just for its crabcakes but also its drug trade. Yet Wallace focuses on the positive, documenting the food vendors and people who made the market a neighborhood hub before it was torn down and redeveloped in 2022.

Another photograph by Wallace purchased by Johns Hopkins, Young Boxer, features a pre-teen in training at Upton Boxing Center in West Baltimore's Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood—ground zero for the 2015 riots and where Gray lived and died. Standing in a fight stance, the adolescent stares into the camera with a look of both innocence and intent, partaking in an activity deemed unsuitable for kids his age by the American Academy of Pediatrics but popular in his community.

"Growing up, activities like boxing, jujutsu, and especially basketball let me be part of a team and see places beyond my own neighborhood," says Wallace, who played basketball at Bowie State. "I attribute those activities to my success today."

Though Wallace has evolved from pure photography to large-scale collages and art installations, she considers photography core to her mission. "People here distrust cameras because the media took so many photos during the riots but gave nothing in return," Wallace says. "People feel used, and I'm trying to change that." Often, Wallace invites subjects to weigh in on how they want to be portrayed; she gives them prints to hang in their homes. "I tell them, 'We made this together. I have a copy, and this your copy,'" she says.

Ernest Shaw Jr.

Painter Ernest Shaw Jr. says art can open minds and transform perceptions—or at least jump-start the process by exposing people to the unknown. "Change starts with getting out of our silos," he says. "You can't automatically alter someone's perception, but it can happen bit by bit through exposure."

Image caption: Ernest Shaw Jr.

Image credit: eshawart.com

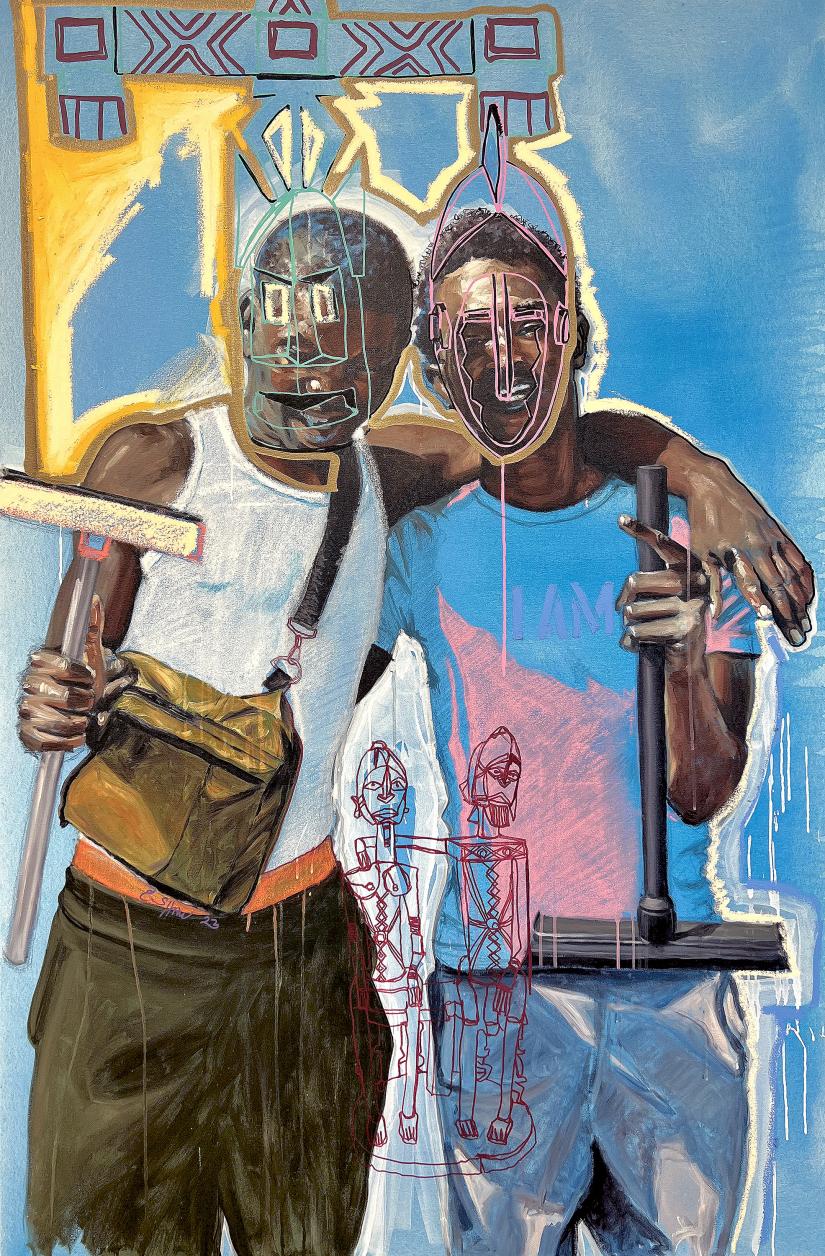

Originally from West Baltimore, Shaw graduated from Baltimore School for the Arts before attending Morgan State University, earning an MFA from Howard University, and devoting his life to the authentic portrayal of Black people "because there is no other subject I find as complex, misrepresented, and misunderstood," he says. His painting acquired by Johns Hopkins, Crossing Godz 5, attempts to reverse negative stereotypes by highlighting the decades-long controversy in Baltimore of young people washing car windows for money.

The painting portrays two teens who cleaned windows on the corner of North and Maryland avenues, near Shaw's studio. "I saw them out squeegeeing in a downpour of rain, and it hit me: These kids aren't out there by choice," he says. "They're out there as a last-ditch effort to salvage their humanity after being part of a failed school system, a failed health care system, a food desert—the list could go on."

In this and other paintings, Shaw integrates African art and iconography to remind viewers of the African roots of many Black people in the United States. Masks from the Dogon ethnic group in Mali (in West Africa) enshrine the teens' faces, while the squeegees call to mind the crooks and flails carried by Egyptian pharaohs. "I'm trying to dispel the myth that everything our enslaved ancestors brought from Africa was erased," Shaw says. "There's too much evidence to suggest that African Americans are still African—and that the history, science, and culture prior to 1619 live on in Baltimore and elsewhere."

Image caption:Crossing Godz 5

Image credit: Ernest Shaw Jr.

Sebastian Martorana

Trained initially as an illustrator, Sebastian Martorana crossed over to sculpting upon studying abroad in Florence, Italy, where he spent months marveling over the stonework of masters like Michelangelo and Bernini. "Making a hard material like marble look malleable and fluid seemed like the ultimate challenge, so I switched gears," Martorana says.

Image caption: Sebastian Martorana

Image credit: sebastianworks.com

But the artist is quick to point out that he prefers the bold, dramatic gestures of Bernini's characteristically Baroque style of sculpting over Michelangelo's more restrained Renaissance style. "People always think I'm on team Michelangelo, but I love the dynamic movement in Bernini," he says, adding: "Put Bernini's David up against Michelangelo's David, and I would choose Bernini hands down."

A native of Manassas, Virginia, Martorana earned a BFA in illustration from Syracuse University and moved back to his hometown to apprentice with a stone carver. From there, he relocated to Baltimore to pursue an MFA in sculpting at MICA while building an independent business in relief carvings, plaques, and other forms of stonework for commercial, private, and government-based clients, including Johns Hopkins. "I've carved cornerstones and donor panels for Hopkins for more than 15 years, but always as a craftsman and never an artist," Martorana says. "It's a real honor to contribute now as an artist."

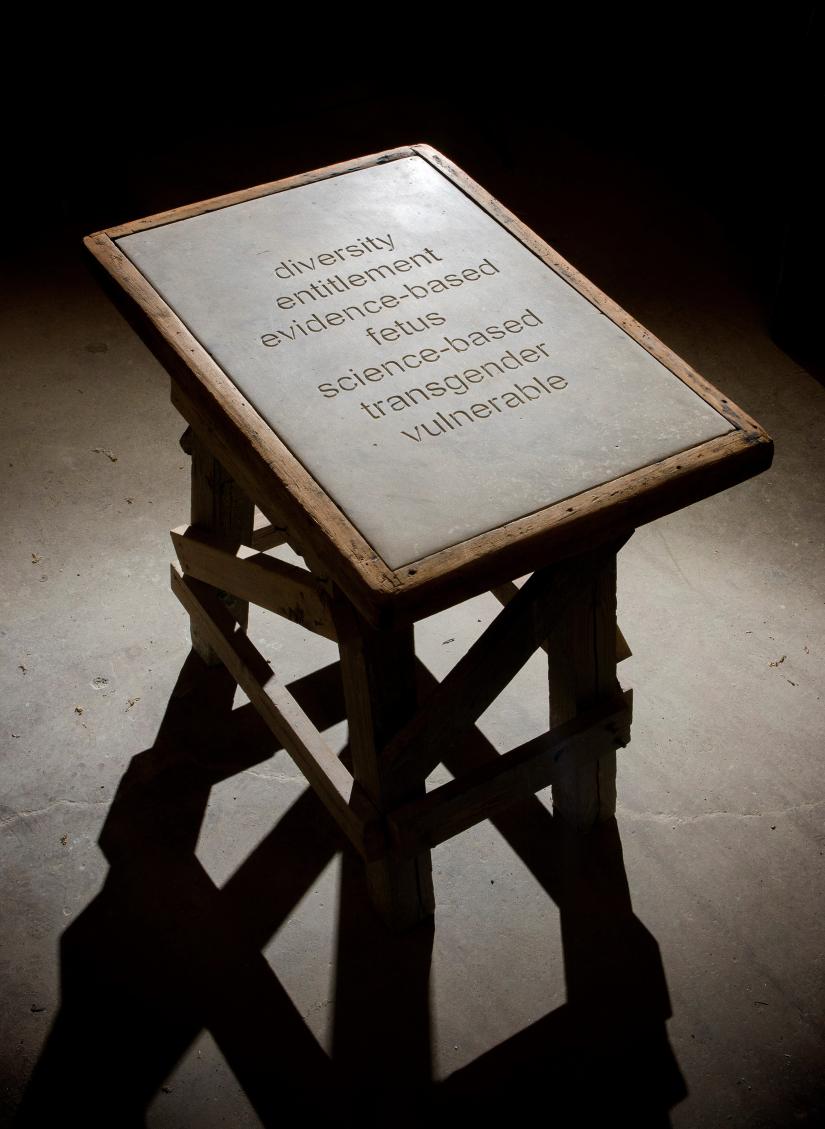

The piece Johns Hopkins acquired from Martorana, Seven Words, differs from the sculptures he typically fashions from salvaged marble—the cushiony pillows, flowing garments, and otherwise soft-looking objects rendered in one of Earth's most durable rocks. Instead, Seven Words features the terms that made headlines in 2018, when the Trump administration advised government employees to avoid using words that include diversity, evidence-based, and science-based to increase their chances of federal funding.

News of the suggestion to exclude these words went viral, with scientists and medical doctors using the hashtag #ScienceNotSilence and calling the measure Orwellian. Around that time, Martorana came across a discarded stone tablet from an abandoned printing press, which had been sitting in a friend's basement. "I decided to use the tablet to make the words permanent, to literally set them in stone," he says.

As part of a printing press, the stone's past life involved disseminating news and information. Martorana tapped into this history, creating a way for audiences to use his art piece to reproduce and disseminate the seven words, rather than having them fade from the lexicon. "The piece is intentionally interactive, inviting viewers to create paper rubbings of the words etched in stone," he says. "In this way, we can preserve the words, propagate them, and learn from this time period in our history."

Image caption:Seven Words

Image credit: Geoff T. Graham

Elena Volkova

Photographer and interdisciplinary artist Elena Volkova uses her camera not as a power-wielding device but as a tool to collaborate on self-expression. Originally from Ukraine, Volkova moved to Baltimore in 1994, at age 18, to escape her war-torn home country, where she and her father used to transform their bathroom into a darkroom on weekends to process pictures. "Photography always appealed to me because it represents truth and fiction at the same time," Volkova says. "Images can hold incredibly deep stories, while inviting imagination and story making."

Image caption: Elena Volkova

Image credit: elenavolkova.com

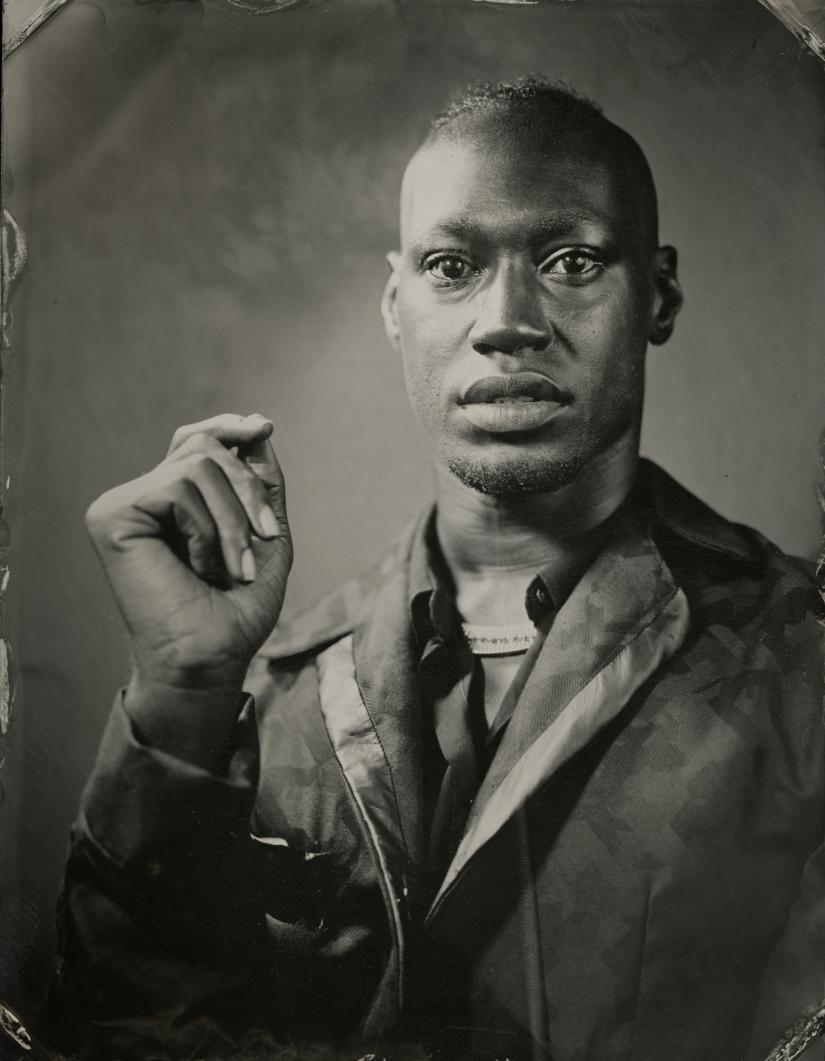

The two photographs Volkova sold to Johns Hopkins stem from her participatory arts project with the Anacostia Arts Center, where she created portraits of people in the historic Anacostia neighborhood in southeast Washington, D.C. "Anacostia began as a Native American settlement, grew into a center for D.C.'s African American community, and now grapples with the push and pull of gentrification," she says. For the portraits, Volkova turned to a form of photography from the Victorian era—tintypes—that involves printing images on thin sheets of metal. She then reprinted larger versions of the tintypes on rice paper to provide "an interesting physicality of the individual that preserves the tintype's imperfect edges," she says.

Although Volkova typically makes conceptual art inspired by theories or ideas, she took a step back for her Anacostia series, allowing the collaborative aspects to drive the process. One of her photographs features an adolescent girl, Vera, whose mom works in a floral shop in Anacostia. "Vera wanted to make her image stoic and grand, without laughter or frills," Volkova says. In another photograph, Volkova says her subject took the opposite approach. "Lake Rose is a drag queen who came to the studio wearing a tuxedo jacket and wanting to show themselves gesturing with their hands," she says. "So that's what we did."

"Ultimately, the Anacostia project is about documenting a part of town that isn't properly represented in the archives or in our culture," Volkova explains. "People need to see themselves in archives, in news stories, and in the art of institutions, but in many instances, whole communities have been overlooked."

Image caption:Lake Rose

Image credit: Elena Volkova

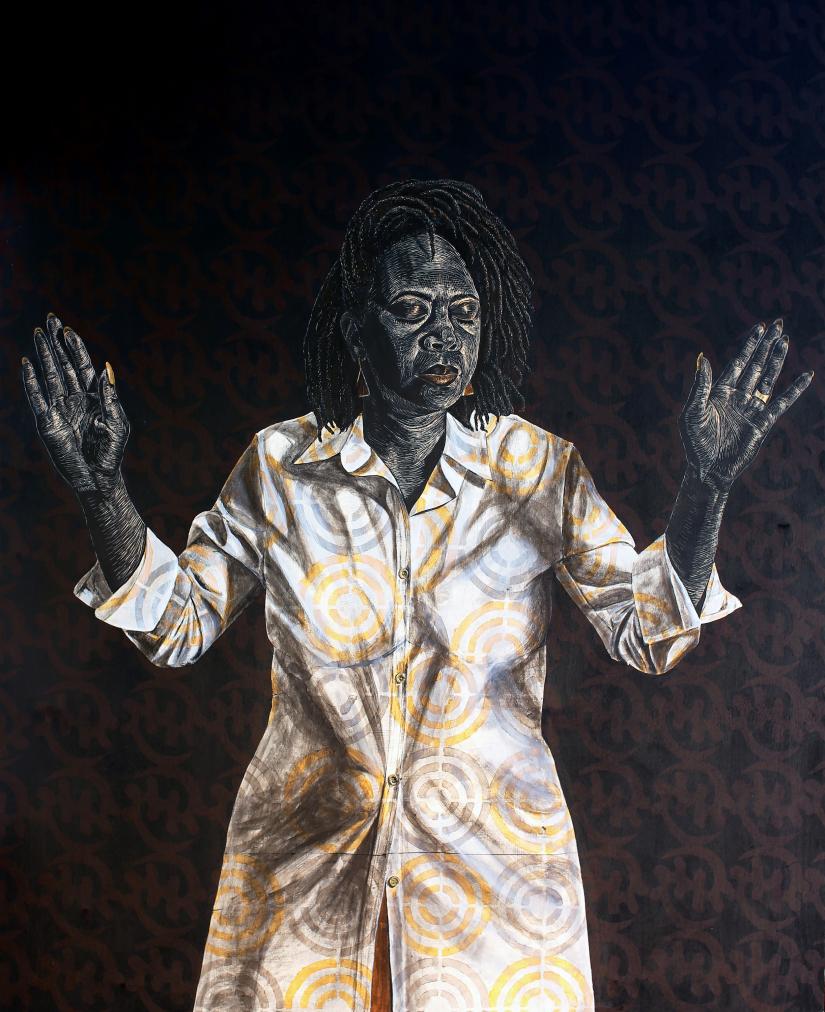

LaToya Hobbs

Painter and printmaker LaToya Hobbs focuses on the Black female experience. Attempting to make up for the dearth of Black women represented in Western art history, Hobbs creates imagery that dismantles stereotypes and captures women on their own terms. "I tap into their presence and power as individuals, beyond the veil of double consciousness that many Black people experience of being visible and invisible at the same time," she says, referring to the term coined by sociologist W.E.B. DuBois in his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk.

Image caption: LaToya Hobbs

Image credit: latoyamhobbs.com

In this seminal collection of essays, DuBois describes the dual experience of individuals from marginalized groups knowing both who they are on the inside and how they're viewed by the dominant culture. Double consciousness, DuBois writes, is the "sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity."

Originally from Little Rock, Arkansas, Hobbs moved to Baltimore a decade ago to take a teaching position with MICA after completing an MFA program at Purdue University. Johns Hopkins acquired two of her large-scale portraits, How Johnetta Taught Us to Pray II and Sistership.

In How Johnetta Taught Us to Pray II, the artist combines both painting and relief carving on wood to create a self-portrait that pays tribute to her grandmother Johnetta. "The piece represents the spirituality and traditions my grandmother passed down throughout my family," Hobbs says. Indentations from the artist's etching form the folds of her skin, while painted elements highlight the yellow swirls of her button-down tunic and the deep-red tones of her lips and fingernails.

To create art like this, Hobbs carves marks, shapes, shadows, and textures into wood, which she then paints (and sometimes collages) to bring figures and scenes to life. Her process is time-consuming and tedious, much like the process of Black women discarding negative beliefs and uncovering their inner truths, Hobbs says. The result is "art unlike anything I've ever seen before, not in scale and not in its complex [way of] moving between positive and negative space," says Bell Brown of the BMA, which exhibited Hobbs's largest and most ambitious undertaking to date, Carving Out Time, a collection of 15 larger-than-life woodblock print panels chronicling a single day in her life as an artist and mother of two boys. "I expect this will become one of the greatest works in art history for generations to come."

Image caption:How Johnetta Taught Us to Pray II

Image credit: LaToya Hobbs

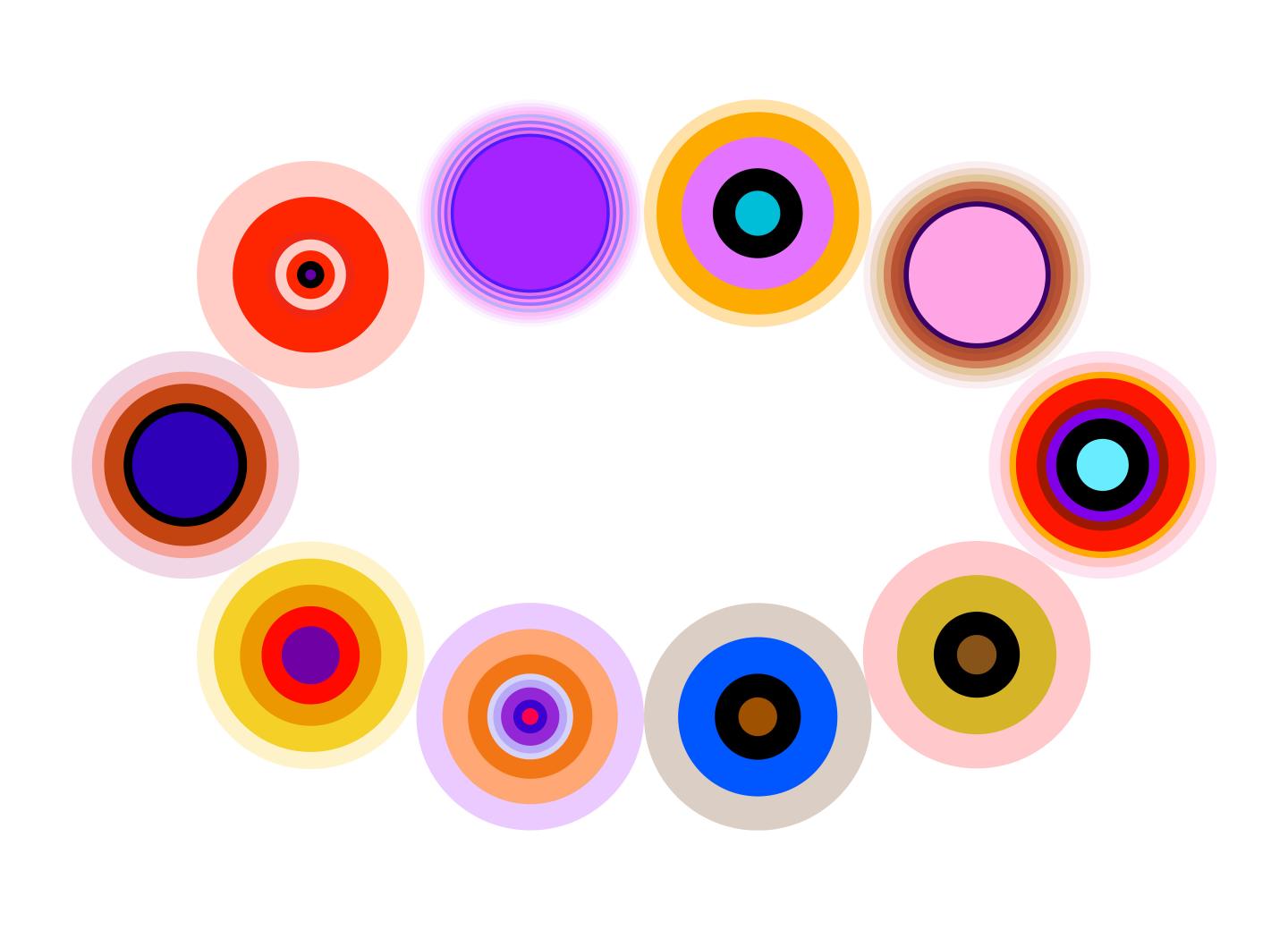

Linling Lu

Abstract painting gained traction in the 20th century as a reaction to artists' longstanding efforts to make two-dimensional surfaces look three-dimensional. In abstract art, the visual language lacks the trappings of reality and consists instead of pure elements like color, line, shape, and form.

Image caption: Linling Lu

Image credit: lulinling.net

Artist Linling Lu communicates largely in this modality, painting circles of vibrant colors that appear to glow and float in space. Her work exhibits a hypnotic quality, enticing viewers to stare at the multi-colored circles for extended time periods, as though in a trance.

In Circle Dance, the metal print set Lu sold to Johns Hopkins, 10 concentric circles reverberate light and energy, representing a rhythmic play of musicality. The connection to music shows up in much of Lu's work, stemming from her years spent studying and playing classical piano in Zunyi, part of the Guizhou province in southern China, where she grew up. Lu moved to Baltimore nearly two decades ago to pursue a BFA, and then an MFA, at MICA.

"Music and nature are important sources of inspiration for me," Lu says. In fact, her attraction to circles comes from her time as a child watching the sun set over the horizon. "The timeless form of the sun and the color transformation of clouds evolved [in my mind] with Chopin's music and [the] solitude [I experienced] as an only child. I tend to forge these meditative memories poetically [in my art] practice today."

"Color plays music for me," Lu adds. "I see art and music as one."

Her luminescent circles harken back to the tondo paintings popular during the Renaissance. Yet instead of featuring figures and scenes from the Bible and Greek and Roman mythology (all popular fodder for Renaissance art), Lu's tondos come across as thoroughly modern and even other-worldly and futuristic. As such, they inspire transcendence to, or perhaps reflection on, a higher realm, beyond the trifles of everyday life.

Image caption:Circle Dance

Image credit: Linling Lu

For Johns Hopkins, the broad range of work by Lu and the five other Baltimore-based artists supports priorities articulated in the university's Ten for One strategic vision, specifically a goal to deepen partnerships and programs that support the aspirations and generate economic opportunities of neighbors across Baltimore and other associated communities.

As the nine art pieces make their way to campuses, artists say they're excited to see Johns Hopkins take this important step.

"I'm thrilled to see a top institution like Hopkins invest in a new visual narrative for Baltimore, and I hope it's the start of a long-term partnership," Wallace says.

Shaw echoes Wallace's sentiment, adding: "The acquisition validates the work I've been doing to overturn negative narratives and illustrate a more complete picture of Baltimore's lived experiences, while celebrating the creative energy of our resilient city."

Posted in Arts+Culture