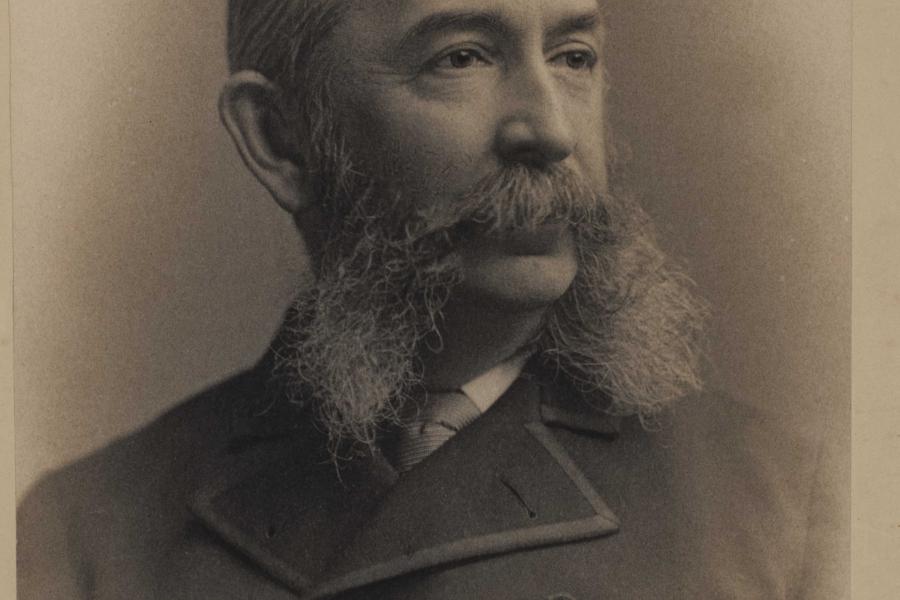

The namesake of Homewood's iconic clock-towered building, Daniel Coit Gilman essentially created the modern American research university when he led Johns Hopkins for its first 25 years. Biographer Michael T. Benson brings this bewhiskered giant and his collegiate contributions to life in a new work from Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gilman spent nearly 50 years in academia, from assistant librarian at his alma mater Yale in 1856 to founding president of today's Carnegie Institution for Science in 1901, with a stint as president of an emerging University of California in between. But, of course, he is best known for being president of Johns Hopkins University, a role he assumed at the school's founding in 1876 and left in 1901. He died in 1908, and in May 1915 the university in his honor formally inaugurated Gilman Hall, the first academic building on the new Homewood campus.

Benson, president of Coastal Carolina University and a professor of history, has long been fascinated by Johns Hopkins. "Places such as Harvard had a 240-year head start, but Hopkins was able to quickly punch above its weight class," Benson says.

Hopkins' success as scholastic upstart can largely be attributed to Gilman's pioneering ideas, motivational oratory, and dogged recruiting, as Benson explores in Daniel Coit Gilman and the Birth of the American Research University, the first biography of this giant of academia in some 50 years. It is also the first to make extensive use of Gilman's expansive trove of personal papers and correspondence. Readers get a glimpse of the man behind the imposing muttonchop whiskers.

The Hub connected with Benson to discuss his book, released by JHU Press in October.

What inspired you to write this biography?

I had read Gilman's inaugural address from 1876, which is probably the gold standard of presidential inaugurals. In the spring of 2017, a colleague and I were visiting the Johns Hopkins campus. We were in the little bookshop inside the Homewood Museum and I asked if I could purchase a biography of Gilman. There was an archivist there who said, "Well, no one's really written anything about him for the last 50 years." I thought that was a tremendous disservice, not only to him but more importantly, to higher education writ large given how remarkable the American research university is. So, they said, "Hey, why don't you take a shot at writing it?" I submitted a proposal to the Hopkins Press (which Gilman helped to found in 1878) and was delighted when they accepted it. That I was able to tie the book project into earning a Master of Liberal Arts at Hopkins during the process was an added bonus.

What did your research process look like?

I spent the bulk of my time in two places. One was the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale, where Gilman was an undergraduate, and is home to a lot of his personal papers and correspondence and journals. And then I just fell in love with the Milton S. Eisenhower Library and its staff. Time spent in the Chesney Medical Archives was also very helpful.

Prior to starting his long tenure at Hopkins, Gilman was president of the University of California. But he served only three years before resigning. What happened out West?

What he ran headlong into were the people—members of a very formidable lobby called the Grange—who really advocated for agricultural and technical education. They felt you couldn't have a university that was focused on both the more traditional liberal arts and technical education. They saw the two as wholly separate. And then they were the ones really advocating for more of the land grant money to go toward farming, the trades, and mechanical education as opposed to Gilman, who really wanted to see a university focused on everything, from soup to nuts in terms of subjects and course offerings.

His whole career had been in private institutions, so now he's kind of thrown into having to lobby, and it was just this persistent struggle with the legislature that questioned everything he was trying to do. When he heard that something was percolating in Baltimore, it was a perfect opportunity for him to come back to his East Coast roots. And in those days, it was easier to get from Baltimore to London than it was from Baltimore to Berkeley.

Image caption: Benson Talks About Daniel Coit Gilman Book

Video credit: Coastal Carolina University

What were his influences as an academic reformer?

After graduating from Yale, he went to Europe for almost three years and had a chance to go and investigate all the great universities of the "Old World." He spent a lot of time in Germany, France, and England. If you wanted to get a PhD in the 1840s and 1850s, you went to Germany. And if you wanted to study medicine, you went to Germany. It's an immutable fact that in terms of graduate education, Germany was far ahead of the United States. And so Gilman recognized the German model of emphasis on primary research, and then the British emphasis on the seminar method, with full-time faculty serving in so many ways as mentors. And then he had the idea of melding the two, which had never ever been tried before.

The book recounts a trolley passenger passing the original 1880s Hopkins campus in the Mount Vernon neighborhood and mistaking the university for a piano factory. What's the story there?

There's a quote in the book, I can't recall who said it, along the lines of "Hopkins spent millions for research but not one penny for show." When James Angell, president of the University of Michigan, spoke at the ceremony commemorating Gilman's tenure, he said he was so proud of the fact that Gilman put the money into people as opposed to squares and quads and alumni centers. He didn't use those phrases, but yes, whatever capital they had went directly into hiring the best faculty you could find. These graduate students had attended picturesque campuses in bucolic settings, so the stark contrast with downtown Baltimore was really quite jarring.

There's no other story in all of higher education of a university president going out and recruiting like Gilman. I mean, he went to Europe and all along the Eastern seaboard to hire the six original faculty members. He knew that a great faculty was what was going to attract the talent of the fellows and the graduate students. And that's exactly what happened.

What surprised you about Gilman?

As I got more into his life and into his letters, I learned of all these personal challenges he had. He had a brother who was convicted of embezzlement and went to Sing Sing to serve hard time. Gilman's first wife, Mary Van Winker Ketcham, died, and one of his daughters was quite sick early in life. Gilman's sister came to live with the family and care for her. His youngest daughter, Elisabeth, went on to have quite a career as a politician, running for office many times. She was an amazing advocate for social justice and for immigration at a time when that was not happening in a lot of places, particularly in Baltimore.

What do you hope people learn from this book? What relevance does his life have today?

Gilman was a tremendous visionary and powerful orator and used this phrase in his 1876 inaugural speech when the university was a very modest set of buildings on Little Ross Street: "We launch our bark upon the Patapsco, and send it forth to unknown seas." No one had any idea what Johns Hopkins University would turn into, but Gilman and the trustees—along with the original faculty and the remarkable classes of graduate students—knew that they were part of something unique and transformational. The model of today's modern research university—with the teaching hospitals, billions of dollars of sponsored research, and pathbreaking discoveries—was spawned by Gilman and his colleagues. And we stand as the beneficiaries of that 19th-century temerity and commitment.

Posted in University News

Tagged history