- Name

- Johns Hopkins Media Relations

- jhunews@jhu.edu

- Office phone

- 443-997-9009

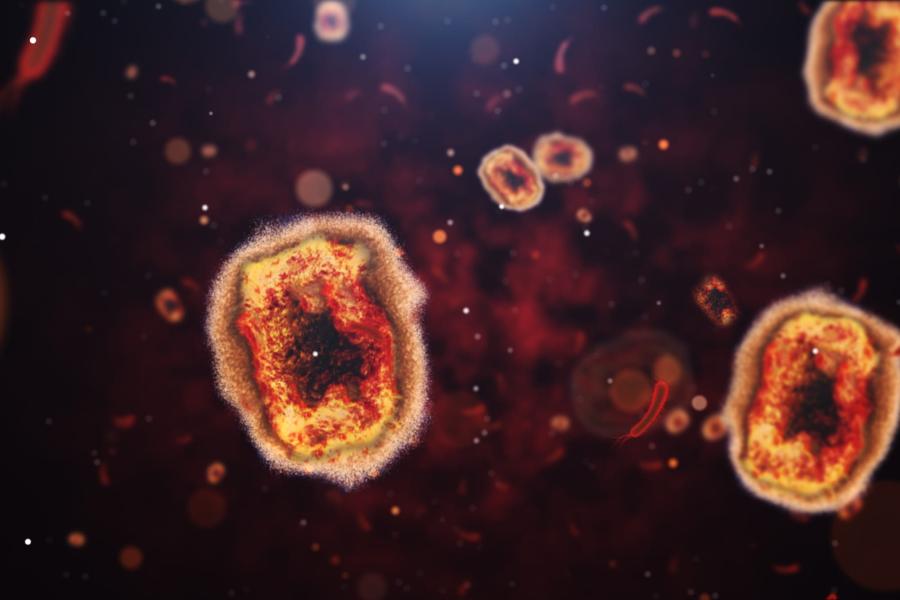

In the middle of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, we're facing a second global, viral crisis: monkeypox.

On Thursday, the Biden administration declared monkeypox a public health emergency in the United States. Is the United States ready to deal with the possibility of twin pandemics? COVID-19 exposed the shortcomings in our national health care infrastructure, from health equity issues to our vulnerability to supply chain hang-ups. Has our experience with COVID-19 given us a roadmap for doing a better job managing monkeypox, or have we been caught on our heels once again?

The Hub reached out to experts from across Johns Hopkins University for their thoughts on those questions and for suggestions on how the country might get ahead of the monkeypox outbreak.

We're unprepared for this emergency—and the next

Amesh Adalja, assistant professor, Bloomberg School of Public Health, and senior scholar, Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security

The most striking aspect of the U.S. response to monkeypox is how flawed it has been and how mistakes characteristic of the COVID-19 response were repeated. For example: Exclusive reliance on CDC-affiliated labs for initial testing hampered the ability to identify cases, onerous paperwork to administer antiviral treatment disincentives its use, and bureaucratic artificial constraints left vaccine in Denmark for far too long. What unites these failures is the lack of a proactive stance that is able to rapidly rise to the occasion; instead an overly bureaucratic stammering seems to be the best the government can muster. This does not bode well for the next infectious disease emergency, let alone the next pandemic.

Strategic shortfalls challenge our public health response

Tinglong Dai, professor of operations management and business analytics, Johns Hopkins Carey Business School

From a logistics standpoint, I've observed that the U.S.'s monkeypox response has fallen short in at least three crucial areas.

First, inventory planning. In May, President Biden said that our strategic national stockpile housed enough monkeypox vaccine for everyone. That has not proven to be the case, as the stockpile contains 100 million doses of an older vaccine (ACAM2000), which has rare but severe side effects, but only 2,400 doses of a newer and safer vaccine, Jynneos. This is akin to a newsstand stocked with yesterday's newspapers.

Second, urgency and agency. Since 2020, a Danish company, Bavarian Nordic, has been producing millions of doses of Jynneo. The facility had to pass an FDA inspection before the doses could be shipped. Notably, the facility had passed inspection by the FDA's European counterpart, the European Medicines Agency, but it still took two months for the FDA to complete the inspection. Every day was a missed opportunity given the disease's rapid spread.

Third, rollout strategy. Jynneos comes in two doses. We learned from the COVID-19 vaccine rollout that when two-dose vaccine supplies are limited, prioritizing first doses is a rational strategy. In fact, despite their more limited supply, countries using this "first dose first" strategy, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, were able to vaccinate their citizens faster than the U.S. This time, local public health agencies across the nation have been applying the same strategy, but the FDA has been opposed to it, citing the need to adhere to product labeling.

The nation's big test is still ongoing, and I remain hopeful that its logistics and supply chain aspects can be improved. If we fail to contain monkeypox this time because of poor logistics, we will have no excuses.

The window of opportunity to act is starting to close.

Tom Carpino, doctoral student, Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Bloomberg School of Public Health

The emergence of monkeypox virus (MPV) is a global threat that must be taken seriously by all. In a span of only a few months, this pandemic has infected more than 25,000 globally and is circulating amongst networks in 75 countries including the US. Now a public health emergency according to WHO, states of emergency have been declared in three U.S. states. While intense pain, lesions, permanent scarring, and at least 10 deaths are associated with this specific strain of MPV, asymptomatic cases have been identified. We also know the predominate mode of transmission is physical contact, which can affect anyone.

Also see

Experts and advocates across the country have been promoting government agencies to act more quickly to control this outbreak, yet the rapid global increase in cases suggest we may have missed the opportunity for containment. Additionally, the disproportionate global allocation of vaccines has resulted in many cities, states, and countries yet to open vaccine sites and leaves many high-risk communities vulnerable. For the highest risk individuals without access to treatment or paid sick leave, isolation for three weeks through the course of infection will be impossible. We need a public health infrastructure and resources to support the isolation and treatment of individuals experiencing MPV. Since it is highly possible for MPV to spread in the general population, we must act now before this becomes endemic. We must act swiftly, together, and without fear, misinformation, or stigma to abate this public health emergency.

Just how worried do we need to be?

Jason Farley, infectious disease epidemiologist and ID nurse practitioner, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing

Mortality is low, typically less than 3%. That said, monkeypox infection may cause painful, disfiguring symptoms and lead to significant time away from family, friends, and time off work. Once infected, a person can transmit by any form of human-to-human and human-to-animal contact. This includes through respiratory droplets, touching objects, and physical contact. I believe everyone should have an appropriate level of concern about this illness. Anyone can acquire monkeypox with the right exposure. This is not limited to gay men and historically has had a major impact on men, women, and children throughout the world.

This outbreak highlights so many challenges with health equity. African scientists have warned us about this possibility and this is certainly not the first time we have seen monkeypox cases in the United States or in the UK. I think this outbreak again asks resource-rich nations to consider how globalization, deforestation, climate change, and travel will continue to impact disease spread and how we must strengthen our resolve to address global health challenges. An infectious disease in any location in the world can be in our backyard in the blink of an eye.

Posted in Health, Voices+Opinion

Tagged public health, pandemics, monkeypox