Shortly before joining a group of Johns Hopkins students for a conversation on Wednesday, disability rights advocate Emily Ladau had a medical appointment she described as a "complete revelation."

It turned out her nurse practitioner was a bilateral amputee, and immediately she and Ladau, who has used a wheelchair her entire life, could break down barriers. "I have never had a health care provider who in any way felt representative of me, my experience. And suddenly here I had a health care provider come in who was visibly disabled, who immediately jumped into conversation with me about it," Ladau said. "I didn't realize until this exact moment … what a relief it was to not feel like I needed to explain myself when I was receiving health care, because that explanation was already understood. I didn't feel like I had to justify certain parts of myself."

Image credit: Twitter

As part of Disability Pride Month—and as the 32nd anniversary of the signing of the American with Disabilities Act approaches on July 26—Ladau took part in a virtual discussion with Hopkins students with disabilities. The event was sponsored by Equal Access in Science and Medicine, the SGA Disability Caucus, Student Disability Services, and the Office of Diversity and Inclusion.

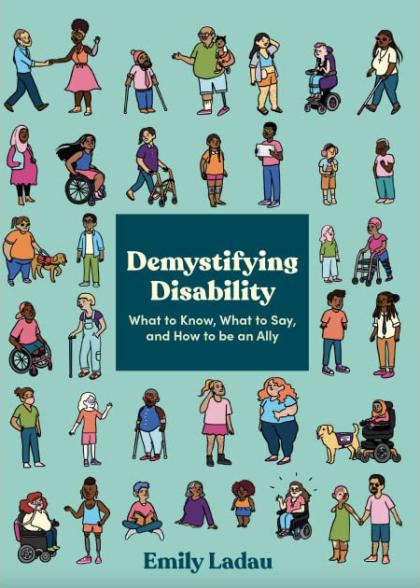

Born with Larsen syndrome, a genetic physical disability, Ladau first ventured into advocacy at a young age as a guest on Sesame Street. Today she is an activist, speaker, and co-host of the Accessible Stall podcast. Her book, Demystifying Disability, was called "a fantastic primer for improving your understanding of disability and ableism" by NPR.

During Wednesday's event, Ladau explained that even as her career and advocacy has evolved, so too has her view of herself.

"When I was younger, the biggest compliment that you could pay me was to say that you didn't think of me as having a disability or to say that you forgot that I used a wheelchair. It wasn't until I got older that I began to realize that when someone would say that to me, it wasn't a compliment," she said. "They were really telling me that they needed to erase a part of me in order to see me as a whole human being. And I no longer wanted to feel that way, because I am proud of who am.

"There is struggle in who I am, there is celebration in who I am, and it's a very nuanced and complex experience," she continued. "I'm deeply human like anybody else, and disability is part of that experience."

She explained that part of her experience includes facing challenges in systems that are not designed to accommodate her. Transportation, for example, is a significant challenge for Ladau, who resides in New York City, where less than a quarter of the city's subway stations are fully or partially accessible for people who use wheelchairs.

"That has ramifications not just for people who are trying to access transportation, but for people who would need [transportation] to access education, health care, employment, socialization, being able to get out to get groceries," Ladau said. "When one system isn't accessible, it then shuts us out from all other systems."

Image credit: Penguin Random House

And yet, Ladau says, there are many people who want to be better allies to people who have disabilities. In some cases, better allyship includes paying closer attention to the language used to describe people with disabilities.

"The first thing that I remind people is that disability itself is not a bad word," Ladau said. "We are so afraid to even use the word that we often relegate disability to the margins of marginalization."

Better allyship also means closely examining—and correcting—ableism, which Ladau described as "attitudes, actions, and circumstances that devalue someone on the basis of them having a disability or based on the assumption that they have a disability." And better allyship requires having challenging conversations about the needs, rights, and experiences of people with disabilities.

"It's about conversation, community collaboration, and constantly being willing to engage," Ladau said.

Ladau was invited to speak at Hopkins by a grassroots group of students, faculty, and staff who organized programming for Disability Pride Month. In addition to the talk, the group is handing out pins supporting disability pride at some of the university's campuses to celebrate and recognize the contributions of people with disabilities. They are also partnering with Kennedy Krieger to host adaptive sports that are inclusive of people with disabilities.

Posted in Voices+Opinion

Tagged disability