This article appears in the Spring 2022 issue of Arts & Sciences Magazine. Black Beyond Data is part of an occasional series that highlights Johns Hopkins faculty whose work examines issues around racial inequity, discrimination, and structural racism.

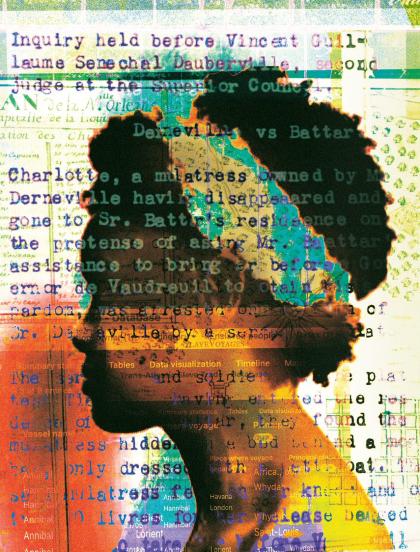

On a spring day in 1751, Charlotte, an enslaved teenage girl, went on a quest to petition the wife of the governor of Louisiana to grant her freedom. Charlotte had become acquainted with a ship captain recently arrived from Martinique, Sieur Pierre Louis Batard. He had promised to help Charlotte arrange an audience with the governor's wife, Madame de Vaudreuil.

On this May morning, Batard sent word to Charlotte that de Vaudreuil was willing to meet. Charlotte hurried to Batard's home, but he was not there. She spent the day awaiting his arrival in his house. But as evening arrived, so did a group of soldiers sent by Sr. d'Erneville, the man who both had fathered her and owned her. Charlotte hid under some mosquito netting in Batard's bedroom. When the soldiers discovered her, she asked them to look at the situation from her perspective; she just needed to wait a little longer for Batard to return. Charlotte explained that if they returned her to d'Erneville, he "would have her whipped unmercifully." She even offered them a sum of cash, 100 livres, that she had carried with her.

"Charlotte did more than run away from her father and owner," Jessica Marie Johnson writes in her book, Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World. The book won the 2021 Wesley-Logan Prize from the American Historical Association. It also won the 2020 Kemper and Leila Williams Prize in Louisiana History, among other accolades. "She combined flight, appeal, allyship, and willfulness in her defiant bid to escape bondage. She demanded to be heard."

Telling Black stories

Johnson is an assistant professor in the Department of History at Johns Hopkins and a non-resident fellow at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University. She discovered Charlotte's story buried in the Records of the French Superior Council of Louisiana and the Louisiana Historical Center. Charlotte's bravery, quick thinking, and confidence emerge from these records, much as the courageous young woman emerged from her hiding place in the ship captain's room.

This is one of Johnson's passions as a historian. To tell the stories of Black people—particularly Black women—in the Atlantic African diaspora during the centuries of slavery. She highlights the relationships, warmth, and intimacy they created despite the harshest of circumstances, as well as the ways in which they wielded intelligence, creativity, and interpersonal skills to strive for freedom.

But Johnson is equally committed to opening access to the myriad amounts of data that contain information about Black life and Black people, both historical and contemporary. Databases that contain information drawn from records as disparate as the manifest of slave ships, court records, and African American newspapers. She presides over and consults on numerous research projects in which other scholars are mining data sets. Their goal: to discover the lives of Black people who would otherwise be lost to time.

Image caption: Jessica Marie Johnson

"It is shocking and so exciting to read these stories, and I say that as a woman of African descent. It's incredibly validating," says Johnson. "Even just knowing the names of people who lived once upon a time and knowing that they existed and that they fought and they lived. This is the kind of information that really reshapes how you orient to the world if you are a person of African descent. You understand yourself as a part of a longer tradition of fighting to live, fighting to survive, but also successful subterfuge, successful defiance, and humanity. It's about people who lived and had ideas and opinions and emotion. They weren't all nice. They weren't all good or benevolent. That's not the point. The point is they were whole people."

As Johnson speaks, her eyes flash behind tortoiseshell glasses. Each digital humanities project she mentions prompts her to think of another, until she has woven a web of interconnected scholars, each peering into a universe of data to uncover truths about Black lives. The effect is similar to exploring a gallery covered by mirrored mosaics: shimmering and complex and transformed by each change in perspective.

Centering the experiences of Black people

In February, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation awarded a $2 million grant to the Diaspora Solidarities Lab. The lab is a Black feminist digital humanities project that Johnson leads along with Michigan State University professor Yomaira Figueroa-Vásquez. The team is creating a virtual laboratory that spans multiple universities to explore new ways to conduct archival research. They also want to bring these practices to the wider community.

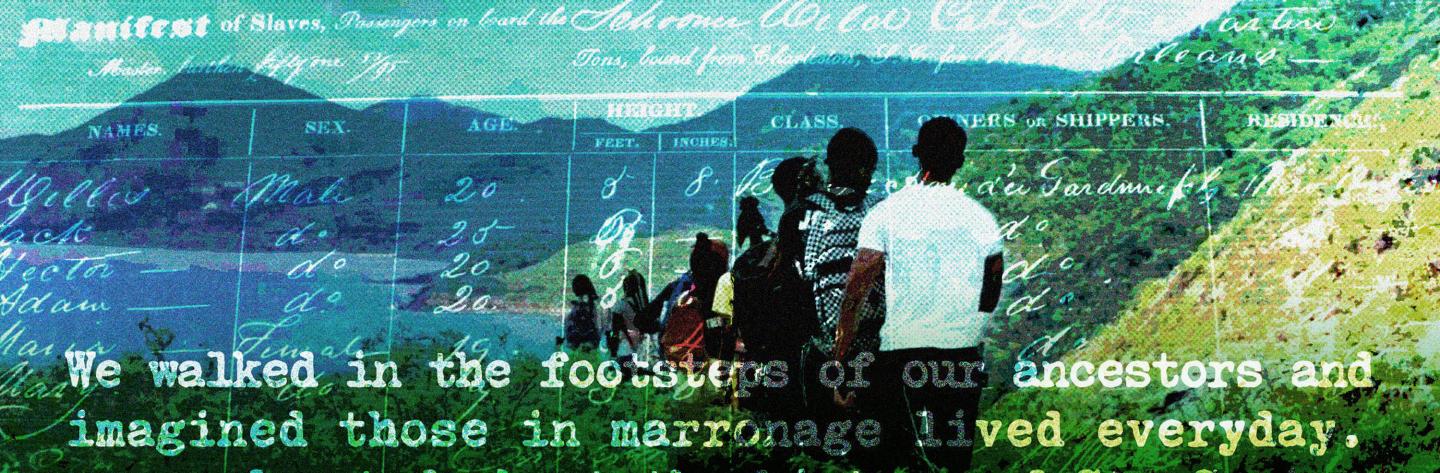

As part of the project, Johnson is creating the Community Knowledge Lab at Hopkins. It will support micro labs including Taller Entre Aguas, which focuses on Black Puerto Ricans; Archipelagos of Marronage, which creates maps depicting where enslaved Black people were surveilled and persecuted; and the Southern Digital Culture Lab, which uses online tools to excavate and share Black history.

Image credit: Collage image sources: National Archives; New Generations Scholars video, “TOUCHING THE EARTH: A Journey to St. Croix.”

Johnson is also one of the leaders of Black Beyond Data: Computational Humanities and Social Sciences Laboratory for Black Digital Humanities. It was also awarded a $300,000 planning grant from the Mellon Foundation. This project comprises three Hopkins-based research projects that use large databases to understand Black life. The Black Press Research Collective is a database of Black newspapers from the United States, African countries, and the African diaspora.

Life x Code: Digital Humanities Against Enclosure is an award-winning initiative created by Johnson and Christina Thomas, a doctoral candidate in history at JHU, that serves as an incubator for several antiracist research projects and practices. Finally, the Risk and Racism project examines how racist assumptions influence diagnoses.

Humanistic methods from a data perspective

Sayeed Choudhury, Hopkins' associate dean for research data management at the Sheridan Libraries, describes Johnson as brilliant, creative, and compelling. "She has this amazing ability to understand humanistic methods even in the absence of data. But with data, she starts seeing all these new perspectives when she thinks about the humanities from a data or infrastructure perspective," he says. "What is even more remarkable is her emphasis on working directly with the community."

The amount of data housed at Hopkins is measured in petabytes—more than a quadrillion bytes of data, Choudhury says. This includes information gleaned from space telescopes, medical studies, and myriad labs. The Black Beyond Data projects are unique in that all revolve around centering the experiences of Black people. "Data are not without biases, without value, without assertions," says Choudhury. "We have to uncover the motives, the biases, and the assertions that led to those interpretations and outcomes."

Johnson's passion for data grew in parallel with her work as a historian. She received her doctorate in history from the University of Maryland, and studied with the renowned scholar of slavery Ira Berlin. However, her work in digital humanities—the use of technology to expand knowledge in history, literature, philosophy, and related fields—grew independently from her academic life.

"I became interested in the digital humanities from the folks who were operating online before Twitter, using blogging, blog rings, online journals, and other online spaces in order to create connections around Black feminist thought," she says. "This was in the early 2000s, and that community, in my opinion, were really some of the first digital humanists to reshape the field. That digital space has been one to share ideas, to organize, and make connections with communities and grassroots organizers."

As Johnson burrowed deeper in her work as a historian, delving into the lives of enslaved and free Black people in New Orleans, the connections she made with other digital humanists took on new resonance.

"A lot of people were organizers, writers, photographers, and artists, creating radical media around issues of social justice," she says. "For me, finding and engaging in that community of folks was incredibly important for the work I was doing around the history of slavery. At the end of the day, I think history is actually about social justice; learning about it, understanding it, and correcting the record that what many people in the U.S. are told about slavery is wrong. And correcting the record is really important."

Image credit: Background images sourced from _Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World_, by Jessica Marie Johnson

Johnson believes that one key way to correct the record is to reframe the way in which we examine the Black experience through data. Many historical data sources about Black people, such as bills of sale for enslaved people, were created by the white people who enslaved and dehumanized them. Recent data sets are also tainted by racism, in the way information is collected, analyzed, or interpreted. Johnson seeks to rehumanize Black people through data and to uncover their hidden histories. Much as she did with Charlotte, the young woman who sought her freedom in 1751. (It would take another quarter century for Charlotte, who changed her name to Carlota, to purchase her freedom from her father for 250 pesos.)

"From the very beginning, of course, we think about how to do this in a way so that we are asking questions about Black life and Black humanity," Johnson says. Each project that she works with adopts an ethics code to ensure the work is non-exploitive and accessible to those outside academia.

Alexandre White, an assistant professor in the Krieger School's Department of Sociology and a history of medicine assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, grapples with these questions as he leads the Risk and Racism initiative, part of Black Beyond Data.

"What sort of material do we treat as data? What do we treat as truth? How do those materials participate in the ongoing dehumanization of enslaved people or allow us to pause and think more deeply about what is fundamentally missing?" White says. "And within that, can we uncover stories of resistance, stories of daily life, any sort of experiences that would trouble the narrative that documents speaking from sites of power would have us believe?"

The practice of turning raw records into a database is tedious and time consuming. Researchers must create a system to organize the data, then code and enter each record. Over time, documents are transformed into spreadsheets, which are linked to become databases.

"That process can continue for as long as we're able to keep adding information; that can be kind of an ongoing perpetual process," Johnson says. "With those sheets, with those tables, with that data, we can see all sorts of things. We can create different kinds of visualizations. We can see more clearly the individual stories within a given set of documents. One of the things the runaway slave ad team [part of the Community Knowledge Lab] was able to do was get a better sense of where people were getting captured in the city. That was information we didn't have before. That gives us a sense of the web of surveillance that surrounded enslaved people in New Orleans."

Communities Controlling Their Own Data

Johnson also seeks to provide people outside of academia with the tools, skills, and data access to enable them to conduct their own research. Since 2017, in addition to her teaching, research, and consulting on other projects, Johnson has worked with a grassroots Baltimore program called New Generation Scholars. It teaches teens and young adults about the African diaspora and the history of slavery. The students take part in leadership development training and travel to important sites in the African diaspora, including Ghana, St. Lucia, Puerto Rico, and New Orleans.

Black Beyond Data also includes a partnership with the St. Francis Neighborhood Center, Baltimore's oldest continually operating community center, which serves people on the city's west side. The center's mission is to eliminate generational poverty, says Lauren Rubin, St. Francis's senior policy strategist. The center organizes an afterschool youth program, health care services, internships, and job training programs. In recent years, the organization has been working to breach the digital divide. St. Francis's staff worked with Comcast to ensure that the families they serve have access to internet. The organization gave away 128 computers at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Then it obtained grants to purchase more computers for families who need them.

Kim Gallon, a visiting associate professor of history of medicine at Hopkins' School of Medicine, has been leading a series of workshops at St. Francis to teach community members how to access and manage the data that is available about them online. The center also hosts a virtual discussion related to Black Beyond Data on the last Friday of each month.

Through the Mellon grant, the center is working to revolutionize the way data is collected and interpreted in the surrounding community. "Oftentimes, when a media outlet or other nonprofits or the government is reporting on statistics gathered about our neighborhood, the takeaways are that this is a neighborhood full of crime, there's a lot of addiction, the kids don't do well in school. That narrative is extremely stigmatizing and further marginalizing," Rubin says. "We've been trying to flip that on its head and allow the community to take control of their own data."

To that end, the organization has created an online community needs assessment that offers participants a wide variety of responses to each question. Many of which focus on their strengths. For example, one question asks what participants do to take care of their health and offers more than a dozen possible responses, including "go to the park" and "avoid tobacco products." Another asks if they have ever been discriminated against while seeking a job. "We tried to be non-extractive, equitable, informational, non-paternalistic, validating, and fair," says Rubin. Participants receive gift cards for completing the survey. The data compiled will be shared with community members, who will be invited to upload photos, videos, and stories to the database to make more complete portraits of their lives. Eventually, the center hopes to train and pay data stewards who will share their knowledge and expertise with others in the community.

Johnson acknowledges that it is a fraught time to be fighting to tell more complete histories of Black people. And, to empower Black people to take an active role in the creation, propagation, and exploration of data created about them and their ancestors. Conservative activists have been railing in state legislatures and on cable news about critical race theory. Florida recently passed a law that would prohibit schools from teaching anything that could make people feel "discomfort" around race.

"The battle is over how we tell the story of the country. It's about how we tell the story of how we relate to each other, and it's also about how we are laying the foundation for a new generation of activists," she says. "We cannot have a generation ill-informed about the past, but along with that, we can't afford to have a generation that does not see each other in relationship to each other, in community and solidarity with each other."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged race, jessica marie johnson, digital humanities