They are fugitives, the keepers of this online space. They are also historians, women of color, graduate students, and daughters. But here they are fugitives, in the sense that to be authentically Black in American academe requires one to live in a state of fugitivity.

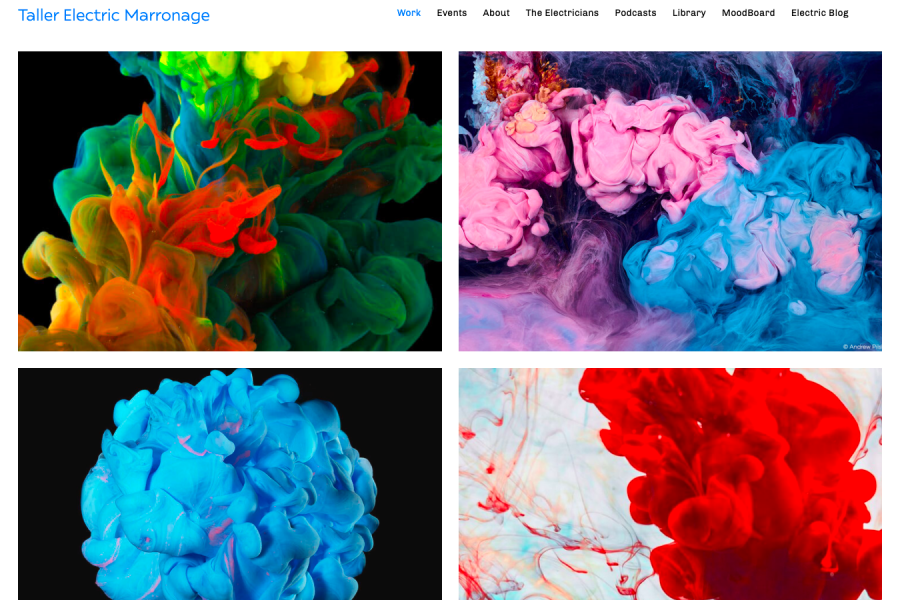

The space: Electric Marronage. It defies the usual bounds of description. Its creators and caretakers—the electricians—sometimes call it a digital collective, a workshop, or a fugitive underground, when pressed to define it. Physically, it's a multi-layered website that houses the scholarly and creative means to break through various types of confinement—physical and otherwise—and also the creations produced by doing so, in the form of photos, videos, paintings, blogs, poems, narratives, journal entries, podcasts, quotes, galleries, and workshops.

Electric Marronage, or EM, is designed to bring together scholars, writers, artists, and thinkers in a space free from the dictates and conventions of academia, to explore and express and celebrate. "EM's goal is to build a wide community that takes seriously the key tenets of what it means to be thinking about freedom and escaping the enclosure of academia, of whatever space you come into EM at, and trying to build something beyond that," says Kelsey Moore, who is starting her third year in the Department of History's doctoral program and serves as one of EM's assistant editors.

The collective was born just over a year ago and is now a project of LifexCode: Digital Humanities Against Enclosure, a research project that Department of History Assistant Professor Jessica Marie Johnson created to help students practice using new technologies to mine historical data. Johnson serves as a curator of EM, along with Yomaira Figueroa-Vásquez, associate professor of Afro-diaspora studies in the Department of English at Michigan State University.

What is fugitivity, the guiding principle of EM? It's resistance. It's a moment of joy snatched during tedium or hardship, a colorful turn of phrase defying the grayscale of prescribed language, a wayward action that swims upstream for a moment, a year, a life. Wayward is a word the electricians often use to describe their work—as in unruly, as in un-ruled.

Fugitivity has four rules of its own: "How do you escape? How do you steal? What does it feel like? Whatever." The rules are inspired by the history of marronage—the tradition of the Maroons who escaped enslavement in Jamaica and formed communities outside the mainstream. According to the EM Fugitive Handbook, the Maroon, "through acts of subversion, mapping routes of escape and plotting land—claimed place, and reclaimed their bodies as sites for the construction of alternative visions of freedom." The handbook adds, "Using marronage as its organizing praxis, this forum seeks to offer a historical genealogy of Black resistance grounded in a Black diasporic framework."

"It's thinking about the academy as a way that doesn't always allow for Black thought and Black ways of knowing and knowledge, and how we continue to create spaces for ourselves, fugitive modes of being, about writing and the certain methods that we have to stick to," says lead editor Halle-Mackenzie Ashby, who is also entering her third year as a doctoral student of history at Hopkins. "So we use Electric Marronage as a platform to write the way we want to, kind of un-ruled. And another way of expressing ourselves that doesn't have the dictates and boundaries of the traditional academy."

Ashby led the creation of the Fugitive Handbook, which delved into the four rules in a four-day forum last year exploring Black diasporic resistance. Like the other electricians, Ashby organizes events and fora for EM, curates content, and adds her own.

"Another big component of the site is the blog posting," says Christina Thomas, former lead editor and a fifth-year doctoral student in the Department of History. "How we are personally thinking about not just themes of marronage or fugitivity, but thinking about family and kinship, and then writing the blog and sharing them on different platforms like Twitter, and then seeing the perception from other people. Kelsey and I both wrote about our grandmothers and what have our grandmothers taught us, what is family teaching us. Halle did a blog post about family inheritance and thinking about how kinship has shifted during the pandemic."

Another recent event was a collaboration with Tao Leigh Goffe's Dark Laboratory, based at Cornell, in which the EM founders and Dark Lab founders held a conversation about Black feminism, the land, the body, and the archive. "They really used the space to not only talk about Black modes of being and thinking about coloniality, but celebrating each other's work, and it was really nice to see authors that we've read loving on each other's work, and I think that's what EM's impact is: a space to love, and to build community, during peak moments of violence," says Moore, one of the conversation's organizers.

In March, EM and LifexCode were awarded the 2020 Garfinkel Prize in Digital Humanities from the American Studies Association. The award recognizes excellent work at the intersection of American Studies and Digital Humanities. Within a groundbreaking arena, EM is a groundbreaking example. It's a fitting recognition for the electricians' groundbreaking work, Johnson says.

"Electric Marronage is about creating Black and brown femme-centered networks of community, solidarity, and care," Johnson says. "We hope we are mapping a new way of thinking about Black study and accountability that isn't about extracting knowledge or resources or spectacles of violence, and instead honors our whole selves as part of what and how we study and build knowledge in the world."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged history, humanities, jessica marie johnson