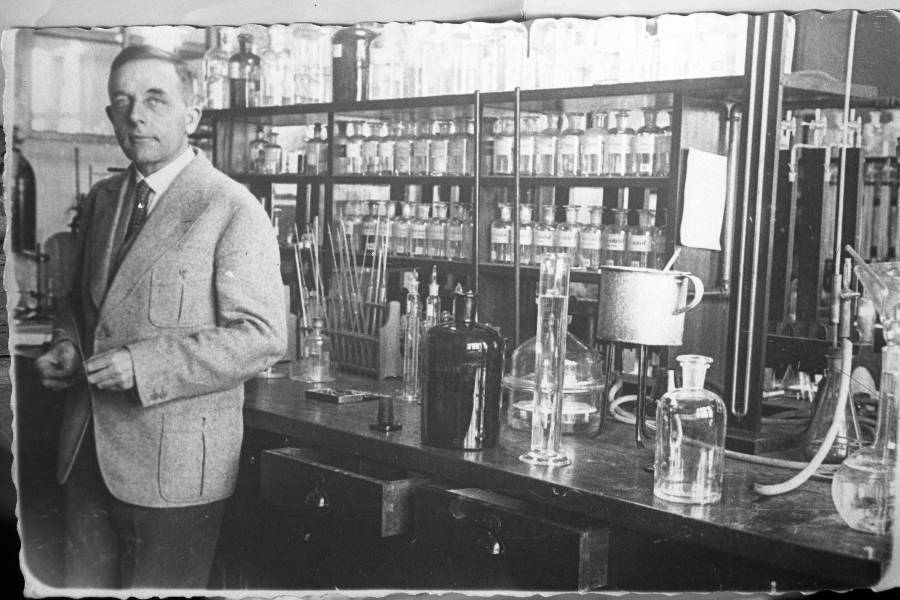

Otto Warburg possessed several traits most despised by the Nazis. He was Jewish and by all accounts gay (although he never admitted it). In 1935, the newly enacted Nuremberg Laws deemed the distinguished biochemist a "first degree Mischling" or "mongrel" because he had two Jewish grandparents.

The "mongrel" label made it even more difficult for Warburg to invite fellow scientists to the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science, the prestigious research institute in Berlin where he worked. Warburg's status as a "half Jew" rendered him a pariah, and his center an object of ridicule in Germany in the late 1930s. Respected foreign scientists stayed away, fearful of losing their academic careers. Others, to be fair, just couldn't stand his gigantic ego.

Despite the discrimination he faced, the ever-resourceful Warburg was aware that he served a special role for the Nazis, who greatly feared cancer and believed the Nobel laureate's research offered hope in curing a disease that Hitler himself was reportedly obsessed with to the point of hypochondria.

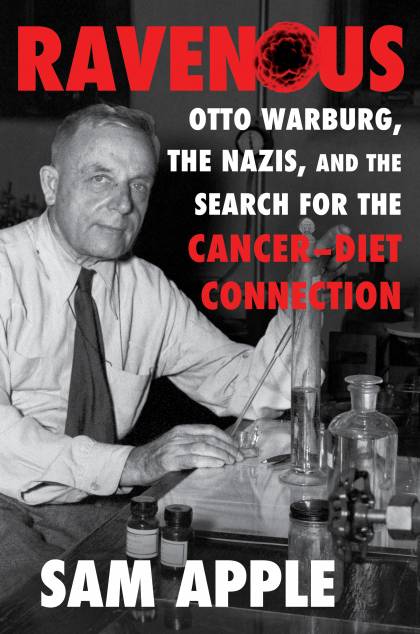

In his new book, Ravenous: Otto Warburg, the Nazis, and the Search for the Cancer-Diet Connection (Liveright, 2021), Johns Hopkins MA in Science Writing program coordinator Sam Apple chronicles the intriguing tale of Warburg, a complex, arrogant, and controversial scientist who survived WWII-era Germany, despite being Jewish and, by some accounts, living an openly gay life with an Aryan German. Ravenous details how Warburg's research on cell metabolism kept him safe during these years, and how the research itself, once disregarded, has undergone a major resurgence among contemporary scientists

Warburg's pioneering work focused on how cells fueled their growth. In studying rat tumor cells in the lab, he found that cancer cells ravenously consume enormous amounts of glucose (a type of sugar) compared to normal cells, which they break down without oxygen via fermentation. The discovery, later named the Warburg effect, is believed to be a hallmark of most cancers—including in humans.

Apple, a science journalist, first wrote about Warburg in a 2016 article published in The New York Times Magazine: "An Old Idea, Revived: Starve Cancer to Death.". Apple says he was fascinated by science suggesting that tumors could consume glucose differently than other cells do.

"I knew that people with obesity were more susceptible to Type 2 diabetes and heart disease," Apple recalls. "What surprised me was the growing body of evidence that cancer had been linked to this same type of underlying metabolic disruption."

After researching the Times article, Apple felt compelled to dig deeper into a man whose life and work had fallen into disrepute in cancer research circles.

"That's when the story all came together and I had the two things I look for in a writing project: the science that fascinates me and the eccentric character to pair it with as my protagonist," Apple says.

Born in 1883, Warburg was destined for a career in science. His father, Emil, was one of Germany's leading physicists, and many of the world's greatest scientists, including Albert Einstein and Max Planck, were close friends of the family. Warburg studied chemistry under Nobel laureate Emil Fischer and later worked with Albrecht Ludolf von Krehl, a renowned German internist and physiologist. He enlisted in the military during World War I and served in the Prussian Horse Guards. Following the war, he was appointed professor at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology, where he began his research career, and by 1931 he had become founding director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Cell Physiology. That same year he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery of a key respiratory enzyme, a protein that catalyzes a reaction necessary for cells to use oxygen.

Image caption: Sam Apple discusses Ravenous with the Johns Hopkins Science Writing Program

During the Nazi regime, Warburg and his partner, Jacob Heiss, lived in a palatial home in Dahlem, a quiet neighborhood of elegant villas in the southwest corner of Berlin where other Nobel Prize winners resided, and where the institute he directed was located. The lavish country manor was built to his detailed instructions to feature 13-foot ceilings, a stone-tiled hallway, and parquet floors. The inveterate equestrian had also designed a stable for his horses and a sizable riding area. Neighbors, who frequently spotted him through the streets in the boots and spurs he had worn during his military service, referred to him as "the Emperor of Dahlem."

Warburg told his sister Lotte of his suspicions that Hitler's lackeys had placed a note next to his name that read, "retain for another 10 years for foreign propaganda." By choosing to remain in his native Germany for so long, especially when so many other Jewish scientists, including Einstein, had fled the country, he feared he had made a "Devil's pact" with the Nazis.

Those choices, as Apple insightfully examines in Ravenous, would haunt Warburg and hamper his scientific advances in cancer research.

"Part of the assumption is that if Warburg stayed in Nazi Germany that he was pro-Nazi in some way, which isn't true," says Apple, who is Jewish and wrote about the Holocaust in his book Schlepping Through the Alps: My Search for Austria's Jewish Past with Its Last Wandering Shepherd (Ballantine Books, 2005). "He certainly made many poor decisions, but he hated the Nazis as much as anyone, so he got a bad rap in some ways." They harassed Warburg relentlessly, from pressing him to sign a "declaration of Aryan descent" to constantly urging him to respond to the Nazi salute, a gesture he never made.

Despite his belief that he was perfect, Warburg had faults of his own. Self-important and narcissistic, he regularly picked fights with other scientists and made extreme claims about cancer. He once told a gathering of Nobel laureates that his cancer research was all they needed to know and everything else was "garbage." One of his colleagues, Apple writes, said that if measuring arrogance on a scale from 1 to 10, "Warburg rated 20."

In Ravenous, Apple describes how Warburg's research fell out of fashion not long after WWII, overshadowed by a rise in excitement and curiosity about genetic science and DNA mapping. In the decades that followed, scientists regarded cancer as a disease governed by mutated genes. Warburg's discoveries became nothing more than "housekeeping enzymes" that were necessary to keep a cell alive but unimportant in the realms of cancer research.

That is until cancer researchers like Chi Van Dang began to rediscover the importance of Warburg's work. In 1997, while at Johns Hopkins, Dang was tracing the influence of MYC—a so-called regulator gene that has the potential to cause cancer—on cells. He demonstrated that MYC directly targets an enzyme that can turn on the Warburg effect. Building on previous work, Dang and others came to the realization that cancer cells are addicted to nutrients, and unlike healthy cells, lack the internal messaging to conserve resources when food isn't available. Without their source of energy, they can die.

Image credit: University of Illinois Archives

Dang reconnected his research to Warburg's early studies of enzymes and the role cell metabolism could have in causing cancer. He began to investigate the late German biochemist's work more closely, reading as much about metabolic enzymes as possible, and published a paper in the journal Cancer Research regarding Warburg's impact on the field.

"This whole idea of diet and metabolism influencing cancer has been around for a long time," says Dang, now scientific director of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research in Philadelphia. "Although it's seen through different lenses, we now better understand the basic science, meaning that how the nutrients affect the actual cancer cells and immune cells is much better understood."

As much a biography of Warburg as a history of medicine, Ravenous chronicles the evolution of cancer research from the 19th century to the present, with particular focus on its resurgence as a metabolic disease. Recognizing the important role of metabolism has led scientists to consider the role that increased consumption of glucose and glutamine (amino acids) plays in growing tumors.

Metabolism-centered therapies, Apple says, have shown promise. Some researchers have focused on dietary cancer treatments such as feeding mice low-calorie diets or low-carbohydrate diets since carbohydrates break down to glucose. "These diets are not cures but have been shown to limit the growth of various cancers in rodents," Apple says. "We still don't know if they are helpful for humans."

The book's final chapter highlights the much-debated role of Western diets as a significant contributor to cancer cases worldwide. According to Apple, understanding sugar and taking precautions to limit it in our diet have become analogous to tobacco and the protracted period of time it took for people to believe that smoking had deadly effects.

"I can't even convince anyone in my own family to stop eating sugar," Apple laments. "It's just so surprising that science was pointed in that direction, and we still can't find a way to do anything about it. I hope my book will change some minds."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged cancer, nonfiction, metabolism