Sarah was 6 when her father brought her into the ER. Scared and short of breath, she had low blood pressure and a rash covering her torso. "I can't breathe," she wheezed, and her dad, verging on panic, reported that he'd rushed Sarah to the hospital after giving her "a tablet" for an ear infection.

"It was an anaphylaxis scenario, an allergic reaction to the medicine," recalls Melissa Boggan, a Doctor of Nursing Practice student at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. "So I had to do an epi."

An "epi" is a shot of epinephrine used to counteract the swelling of airways caused by certain allergens. "When a patient reacts that way to medicine, the turnaround time before cardiac arrest could be as little as five minutes," says Kristen Brown, advanced practice simulation coordinator at the School of Nursing. "Anybody in nursing needs to know how to handle an anaphylactic reaction."

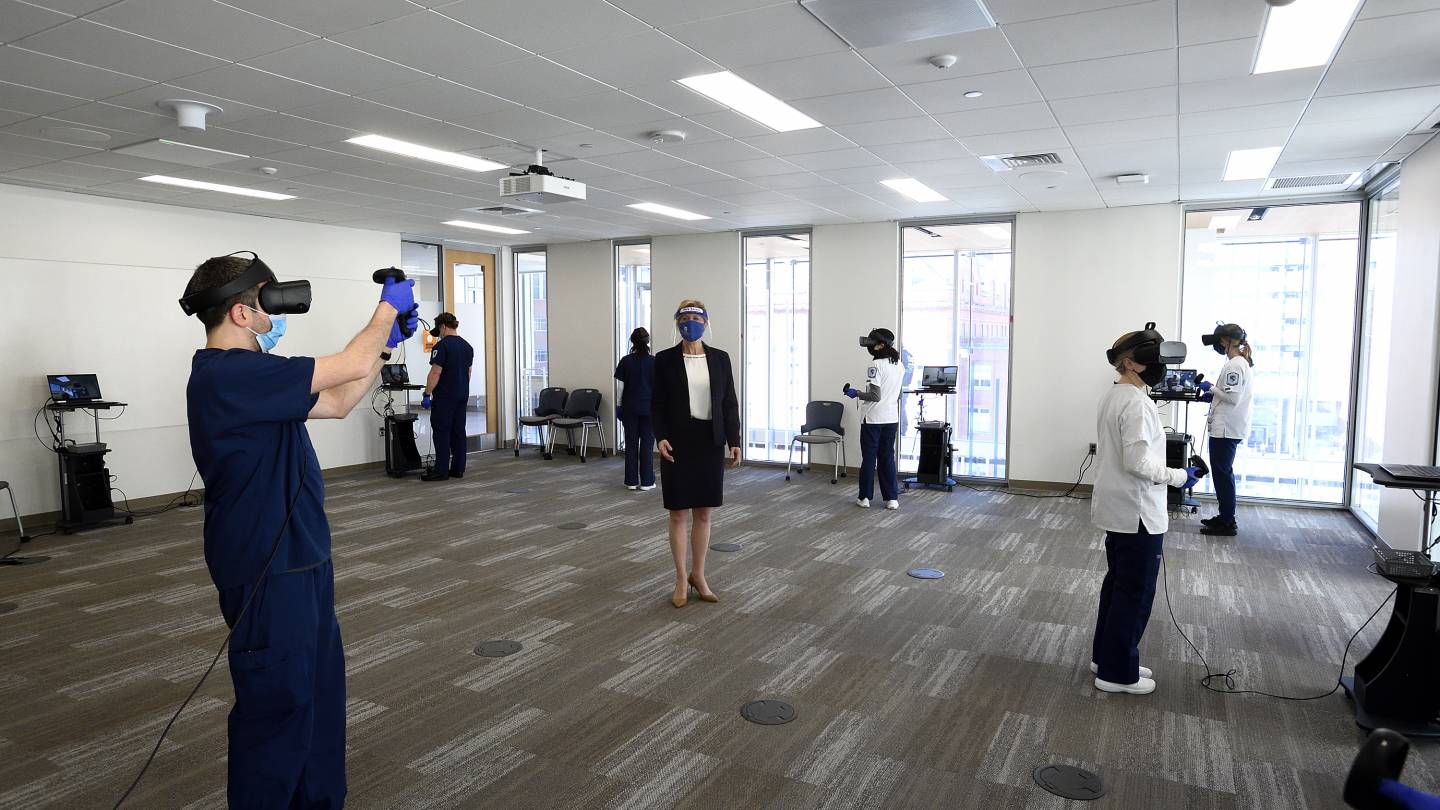

The operative word in Brown's title is "simulation." Sarah, it turns out, was not a real patient. She's an avatar in a virtual reality scenario, one of several used for training by both pre-licensure and advanced practice students at the school. "We rolled out the virtual simulation platform over the summer, during COVID, and were able to train about 400 students in a short time frame," Brown says.

The platform is VR software designed by Oxford Medical Simulation, a Boston-based company vetted by Brown and her team during a search for VR technology, a growing trend in nurse training, prior to the pandemic. The spread of coronavirus "put steam behind moving the project forward," says Nancy Sullivan, clinical simulation director at the school. The software provides two forms of VR—on-screen, conducted via computer at home, and "immersive," which, with the use of an Oculus headset, provides a video game–like experience.

"I first used the on-screen version last semester," recalls Kristin White, a pre-licensure student who graduates from the MSN: Entry into Nursing Practice program in May. "It was an asthma patient. We practiced at home and had to score 80% on different tasks. Then we got to do it with the headset on campus, which was great, almost like real life."

The VR program is part of simulation training, which includes manikins and live actors and complements clinical visits with hospital patients, which have been curtailed during the pandemic. And while the manikins, hooked up to medical equipment, are incredibly lifelike, they're also expensive and take up a lot of space.

Built into the VR scenarios, however, is artificial intelligence, which enables the avatars—stand-ins for patients, for example—to alter their behavior. "Depending on when you do something, the physiological response of the patient changes," Brown explains. "When I put the oxygen on, or how much oxygen I give, changes the scenario. It adjusts to the learner."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Whether on-screen or via Oculus, each scenario places the student in an ER setting with a nursing assistant who introduces a patient facing a particular dilemma. Ray, for instance, a 42-year-old who's had a kidney transplant, is complaining of severe chest pain. Deepak, 64, has been vomiting blood. Boris, 40, is suffering from tremors and appears to be suicidal.

The student has 20 minutes, tracked by a digital clock, to diagnose and treat the illness by running through a series of tasks. Using a mouse or Oculus controllers (one for each hand), the student hovers over the patient's head and body to ask questions and perform exams, respectively, and has 360-degree access to medical equipment, a phone to call doctors, and a cabinet of drugs to prescribe.

Once a scenario's completed, the student is presented with a checklist of analytics—what was done correctly and incorrectly—accompanied by a percentage score. Students scoring 80 and above go to the school's brand-new Virtual Reality Lab, where COVID-19 safety protocols enable them to use the Oculus for the fully immersive experience.

"It's amazing," Boggan says. "You feel like you're in a whole other world."

Even better, for Brown and Sullivan, is the debrief that takes place after the Oculus sessions. A handful of students gather, at a safe distance, with the instructor to review each other's performances. "They do the talking," Sullivan says. "The instructor asks questions, and students discuss while we guide them. So they come out of the room with answers."

They then repeat the scenarios while improving their performance and reducing the emotional stressors that can derail ER procedures. "And they don't run the risk of hurting anyone," Brown says. "They learn critical thinking skills while being exposed to high-risk situations not seen very often. It's great preparation."

It's also the subject of a study Brown and Sullivan are conducting to determine how VR compares with other simulation methods and clinical practice. Early results show that "users rate it very high in terms of usability and the scenario debriefing," Brown says. "And when comparing it to traditional sim and clinical, they either rated it 'similar' or 'higher.'"

This relatively "new tool in the sim toolbox," as Sullivan puts it, could benefit the nursing profession in many ways. "It has implications on enrollment and increased delivery of online programs, allowing nurses to remain in the workforce while advancing education," Brown says. "More education rooted in experiential learning will produce a better-prepared workforce improving patient care."

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged virtual reality, school of nursing