The "pipeline" metaphor popular in higher ed STEM fields describes the journey a student interested in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics must take through increasingly specialized studies to become a tenured faculty member.

The pipeline is infamous for its gender inequity: Women make up more than half of biology doctorate earners, but only 21% of full professors in the life sciences, for example. Attention to this inequity usually focuses on the "water" leaking out—women who begin their studies in a STEM field but leave somewhere along the way before reaching a tenured position. Outdated theories rooted in misconceptions about gender hold that women "leak" because the work is too hard, or they can't balance its rigors with family life, leading to ineffective attempts to propel women past these obstacles.

But research makes clear that those aren't the main obstacles at all; the flaws are not in the "water," but in the "pipes." The leakage occurs because the pipeline itself is often so hostile to women that they move on to another field that offers more equitable opportunities.

"If you feel like your contributions are not valued, why would you continue to give them?" asks Karen Fleming, a professor in the Krieger School's Department of Biophysics.

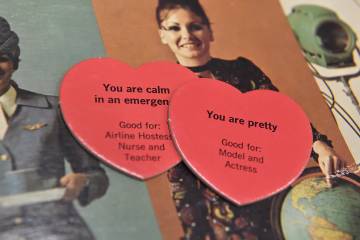

Some of the conditions that create a hostile climate—like sexual assault or quid pro quo arrangements—meet the legal definition of harassment and can be addressed through those channels. More difficult to mitigate are those sometimes called "gender harassment"—nude images posted at work, humiliating put-downs, a bias toward selecting for desirable roles those who most closely resemble a scientist stereotype (usually male and white), or silence following a woman's comment but approval when a man later makes the same point, for example.

"The bias is really small, but you have this death by a thousand paper cuts," Fleming says. "Every day, you have these little tiny cuts."

Essentially, women are being bullied out of STEM career pathways, says Fleming.

At Hopkins, several STEM faculty members have taken it upon themselves to change outcomes for women by repairing the pipeline—making the undergraduate, graduate, postdoctoral, and early faculty years more inclusive of the women whose presence they know will make science better.

"I want a more diverse faculty because I believe that will be more effective and help our departments reach excellence," says Rigoberto Hernandez, a professor of chemistry at the Krieger School. He was tapped in February to serve as a co-chair for the Roadmap 2020 Task Force, a group working to develop the next five-year strategic plan for diversity, equity, and inclusion at Hopkins. The role will allow him to help shape the university's approach. "Emerging data show that a diverse environment leads to more diverse results. Statistically, that means that new discoveries are more likely to be found in a given haystack of results."

Through their years of working to repair the pipelines in their classrooms and labs, departments, and beyond in other universities, Fleming and Hernandez have identified a few practices that seem to make a difference. While each difference may be incremental, they can add up both over time and as increasing numbers of students, faculty, and other leaders implement and model them.

Image caption: Karen Fleming presents her research on ways to improve gender parity in STEM fields at Johns Hopkins Diversity Leadership Council Conference in 2014.

Lifting each other up

Research shows that students are more likely to experience gender harassment from other students than they are from faculty. The offenders have likely picked up cues that the environment is hostile to women, which they may perceive as tacit permission to harass. Faculty members can shift that environment in their classrooms and labs by showing that students aren't only in the pipeline; they're also part of it, Fleming says.

"I can only fix that by pointing out that you are part of the ecosystem, all of you," she says. "When you are sitting in my classroom, you are the STEM pipeline because you are your colleagues in the future, and you must learn at this early age to be good to each other. That's part of how I'm going to run my class: We are going to learn some good science, do some good writing, give each other some good feedback, and be good to each other and lift each other up."

She continues: "I hope the young generation will carry that with them and go on to be leaders that are not only good to each other, but who develop good policy when they mature into leadership positions."

Borrow from social sciences

For the last decade, Hernandez has served as director of OXIDE, Open Chemistry Collaborative in Diversity Equity—a Hopkins-based national group promoting higher ed gender equity through workshops, data, and resources. Hernandez's focus there is steadily changing chemistry's professional culture by guiding department chairs to rethink policies and procedures using techniques from the social sciences to identify and address barriers to equity.

There is some evidence that OXIDE's National Diversity Equity Workshops are having a positive impact on gender demographics of tenure track faculty, he says. "Our success has been noted by the chemical engineering community who now plans to hold a similar event in 2002, and the effort is starting to carry over beyond these disciplines. It's a systemic way of creating change from the top down," Hernandez says.

Normalize the conversation

"If we can normalize [conversations about diversity], this can become part of our everyday conversation, and the gift we will get from that is a greater understanding of how different people interpret communication directed toward them. We need more of this in our community at Hopkins," Fleming says.

Conversations about difference, bias, and inequity are unfamiliar to most and can feel awkward and uncomfortable, but avoiding them won't change anything Fleming says. She intentionally builds them into her lab and classrooms.

Consistently raising issues in those spaces has led to ongoing dialogues in which issues can be addressed without them escalating, she says. One way she's created such dialogues has been to hold weekly journal clubs for the group to read and discuss scientific papers, and to include papers on equity or climate. Another way might be to borrow the concept of the "safety moment" familiar to most labs, holding a "diversity moment" every time the lab meets.

Sailing over milestones

While modifying the pipeline is the top priority, rigorous and equitable preparation of the "water" can't be overlooked, Hernandez says. Most programs use tutoring and mentoring to prepare students to meet each milestone along their educational pathway, but they should also provide experiences that ensure students are prepared to stand out.

"We want them not to just reach the next milestone, but to sail over it to the ones after that," he says.

Know your biases

Biases: everyone has them. They're not personal failings, but products of growing up in a society where certain biases are perpetuated. So instead of pretending they don't exist, and worrying constantly about making mistakes, Fleming recommends learning about them to better understand ourselves and our blind spots. Harvard University's online Project Implicit tests, which identify thoughts and feelings outside of our conscious control, are one way to learn what biases we carry in areas ranging from race and gender to health to social groups.

"I'm disappointed with how I test every single time, but I also realize it's a gift, because I need to be on guard," Fleming says.

Transparency

Hernandez says the biggest challenge to inclusivity is that not everyone feels they are invited because they don't know, transparently, what the situation will be like or that all will receive equal respect. Details that may seem obvious to members of what is effectively the in-group may feel like giant questions marks to those in the out-group.

Stanford psychologist Claude Steele coined the term "stereotype threat" to describe what can happen in situations where negative stereotypes exist about a minority identity. When members of a minority group believe their counterparts may stereotype them, they often experience so much anxiety and cognitive stress that it can affect their performance and lower their achievement, even when they are equally prepared. Steele points to women in STEM and African American students as two examples of groups that frequently experience stereotype threat.

Transparency should be used to erase the separation between those in the loop and those on the outside, Hernandez says. "In events that I host and events that my colleagues host, we're increasingly looking at reducing stereotype threats, increasing transparency, and ensuring the event is inclusive at every level from the ground up," he says.

Learn from mistakes

The time for silence due to fear of saying the wrong thing is over, Fleming and Hernandez say. Modifying the pipeline requires building trust to allow one another to make mistakes and learn from them. Knowledge about diversity and equity is constantly changing; it's inevitable that words and ideas will sometimes come out wrong, but that's a necessary part of the process.

"The challenge now is that we are so sensitive to all of the past wrongs that we're afraid if someone makes another wrong, it's the beginning of a cascade of wrongs rather than a way toward finding a solution to inequities in the pipes," Hernandez says.

Take the lead

The universities whose science departments become truly diverse will be the ones that vault ahead of the rest, Hernandez predicts. If excellence is an institution's goal, he says modifying the "pipes" is one of the most productive pathways for achieving that goal. Hernandez and Fleming both say that university leaders have more agency than they realize when it comes to setting priorities and changing cultures. Implementing a diversity initiative, for example, doesn't go very far on its own, but when leaders consistently and publicly pay attention to inclusivity, practice transparency, and respect differences, cultures can transform. "Creating civil and ethical structures is part of creating inclusive climate," Hernandez says.

And shifting the culture will not take much convincing, Fleming adds; whenever and wherever she raises issues of diversity and equity, she finds that faculty and students are eager to discuss and engage. "It never ceases to surprise me, in a good way, the huge appetite there is for having this discussion," she says.

Fleming, who specializes in the water-to-bilayer protein-folding problem, also has been awarded grants, runs workshops, and gives seminars on overcoming bias and barriers to women in STEM. Her efforts have been recognized by awards from the Johns Hopkins Diversity Leadership Council in 2015 and 2017 and by the Provost's Prize for Faculty Diversity in 2019.

Hernandez, who specializes in the theoretical and computational chemistry of systems far from equilibrium, also serves as director of OXIDE. He received the Diversity Award from the Council for Chemical Research in 2015, and the American Chemical Society Award for Encouraging Disadvantaged Students into Careers in the Chemical Sciences in 2014.

Posted in Science+Technology, University News