When Nathan Connolly launched his Reading Rainbow–inspired YouTube series, he hoped it would help spark a love of reading and a deeper understanding of Africana history in the children who watched it. What he didn't expect was that the series would become just as educational in his own home.

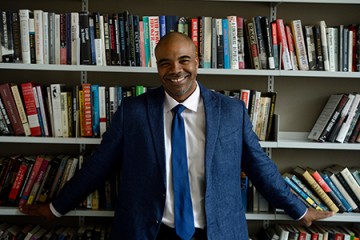

In Storytime with Dr. Connolly, the Johns Hopkins history professor reads from children's books with Black leads, followed by discussion questions, musical numbers, and educational segments edited together with the panache of a classic PBS program.

While Connolly hosts each episode, often in themed or inspired garb, production on the series is a family affair, with his wife, Hopkins instructor Shani Mott, and children—London, 13, Clarke, 10, and Elijah, 7—playing integral roles in the writing, filmmaking, and editing process.

Together, they have become a one-family filmmaking unit, producing 10 episodes of the series in just over two months.

As members of the Department of History, Connolly and Mott research and teach about race, racism, and Black community in the context of history, literature, and politics. This emphasis has found its way into the core of Storytime, with a selection of children's books that each celebrate Black diaspora history in global and historical contexts.

"There's something really valuable to be gained at the meeting-place of history and literature," Connolly said. "But it's been an unexpected bonus to embody values of creativity and collaboration in the house. I think a lot of what happens in K-12 education is that creativity gets drummed out of kids, and so this is trying to salvage something that's natural in children—storytelling."

For each episode, the family starts by selecting a book and scanning each of the pages for the main reading segment. Afterwards, Mott and Connolly choose topics for the post-reading segments, and London begins finding sound effects, music, and clips to complement them.

At the start of the spring, Mott was the only family member with iMovie experience, but soon after they began working on the projects, London took over as the main video editor. Mott says her daughter's dedication to the series and interest in video editing has taken them all by surprise.

Connolly then writes a first draft for the videos, and runs it by Mott, Clarke, and London, each of whom brings a different editing perspective to the process. Guided by their feedback, Connolly revises the script to prepare for the final production. While each episode takes about an eight-hour day to produce, the family usually splits the production work between Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday.

After each episode is assembled, the family gathers for a final Storytime screening, where each member can provide input, call for edits, and make last-minute changes.

Connolly says what started as an educational video series has become an educational tool at home as well.

"Through this experience, we've been able to affirm values of consistency, attention to detail, professionalism, and collaboration," Connolly said. "There's also conflict resolution. As parents, we're learning to appreciate the kids as editorial voices and trust their instincts. When they get an edit right or overrule us, we have to give them the proper kudos."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Storytime originated with Conolly and Mott's work with Orita's Cross Freedom School. Associated with the Pleasant Hope Baptist Church and the popular Baltimore pastor, Heber Brown, III, the school emphasizes hands-on learning of Africana history and provides educational opportunities for Baltimore City students when schools are out of session. When Maryland moved to remote learning due to COVID-19, Connolly and Mott pitched the idea for the series to Pastor Brown as something that could help keep kids entertained and educated during their time at home. He loved it, and they were off.

Early on, the family made videos based on favorite books from their home library. One of the first selections, Little Lion Goes to School, has been a part of the Mott-Connolly household for more than a decade. After several episodes, though, they began to branch out into other children's literature. According to Mott, it can be a challenge to find books that are interesting for a range of children, have the historical context that makes for a strong educational component, and also celebrate Black history and diaspora.

"It has been difficult to find good children's literature that focuses on Black history or Black people that doesn't work to reinforce the status quo," Mott said. "In our family, we often have discussions about the limitations of colorblindness and the limitations of an individual's ability to uplift themselves. We want to find texts that emphasize the importance of community and history."

The books have touched on stories from Kenya, Jamaica, and the American South, while covering historical fiction, biographies, fantasies, and classic African folk tales. After each reading, 10-year-old Clarke relates the story to her own life, before a smash cut to Elijah exclaiming "Oh Snap!" leading into the main educational portion of the video.

During these "Oh Snap!" segments—edited and narrated by London—the family dives deep into topics related to each reading. Topics covered during the "Oh Snap!" segments include Rastafarianism, the history of quilting, trickster animals in folk tales, Blues history, and ableism.

Connolly said it can be a challenge to boil down complicated topics so that they're appropriate for children between the ages of 5 and 14, but having their children there as editors helps keep the videos on track.

"I always give my script copy to my 13-year-old, and then she's basically like, 'Yeah, this is too complicated. I can't pronounce this word. Change this,'" Connolly said. "She's my editor, so I always give her a look at my first draft."

With 10 episodes in the can, Connolly said he's been looking forward to the future of the series. He hopes to continue releasing episodes at least through the summer, and will hopefully involve his children as readers as well as hosts for the additional content.

"I have found it to be so rewarding to do this kind of work as a long-term response to the problems of violence and racism and dehumanization of Black people," Connolly said "It feels like what we're doing here is a part of a much more durable and long-term investment in young people."

For Mott, the social and educational aspects of the show are inextricable from the family that made it.

"I think there's something to be said about seeing this kind of Black joy on screen," Mott said. "The stories are nice, but I think it also matters that it's a Black family that is putting it together. It's joy in action, and that's a powerful thing to see."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged nathan connolly, literacy