They have been hailed as "front-line heroes" of the pandemic crisis, "essential workers" inundated with startlingly high numbers of coronavirus patients in the emergency rooms and intensive care units of hospitals across the world.

For those of us far from the front lines of health care, we can only imagine the anxiety and even despair of the physicians, nurses, and other medical professionals faced with decisions literally of a life-and-death nature. When ventilators are in short supply, for example, how do you determine which patient gets one and which patient doesn't?

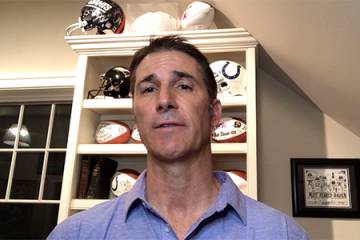

The "moral stress" of workers in the midst of such a crisis is an area of study for Johns Hopkins Carey Business School Associate Professor Lindsay Thompson. An expert in law and ethics, leadership, and disruptive social change in business, society, and corporate culture, Thompson discusses the coronavirus crisis from the perspective of health care professionals, touching on their training for such a highly unusual event, as well as lessons from the crisis that could make health care systems and their front-line heroes better prepared if there's a next time.

Could you explain what you mean, and give examples, when you refer to "moral stress" in the context of health care workers during the pandemic?

Moral stress is increasingly recognized as a self-protective response to morally threatening situations or incidents. Moral adversity and stress activates the normal stress response, and if too prolonged or severe, it can overload capacities for managing stress. The normal stress response is an undifferentiated physiological response—elevated heart rate and blood pressure, physical pain or discomfort, hyperventilation, hypervigilance—triggered by a physical, emotional, or moral threat such as approaching footsteps in a dark alley, witnessing cruelty or injustice, losing a job or loved one, or feelings of shame or humiliation. This response has served humans well as an adaptive mechanism, but the ability to tolerate and bounce back from stress is widely variable.

Moral stress is common among clinicians dealing with terminally ill or traumatically injured patients or in situations where lack of facilities, time, supplies, expertise, or other resources constrain their ability to provide the care needed. This situation is especially acute during the current pandemic where lack of personal protective equipment and ventilators forced clinicians to make decisions about who would receive treatment—thus denying treatment to others. Clinicians can experience this as a personal moral failure and undermine personal integrity, inducing feelings of shame, lack of self-worth, and despair—especially if the situation continues for a long period of time. Then we are dealing with moral distress and possibly moral injury.

What kind of training do health care workers receive to handle such contingencies? And does training even exist to prepare medical professionals for how to decide who gets life-saving care and who doesn't in a shortage of emergency equipment such as ventilators; or how to handle mass fatalities?

Nurses have developed the most robust research and clinical education about moral stress and distress. Yes, there is training for clinicians, especially physicians and nurses, and all hospitals and health facilities have protocols in place for handling such situations of emergencies, disaster response, and pandemics. These protocols are updated regularly, and disaster preparedness drills and simulations are part of a hospital's regular routine, just like fire drills.

There's also the physical stress of working a medical shift during a crisis. To what extent might that contribute to the moral stress of the caregivers?

It is well understood that clinicians and clinical support workers who work extended hours and extra shifts, especially under stressful conditions of scarcity, overload, and trauma, are more vulnerable to moral stress.

Are there individual practices and routines that caregivers in such situations can use to help alleviate their stress?

Self-care is important for caregivers. One of the most important things is for caregivers to honor themselves by exercising responsible self-stewardship—sleep, nutrition, rest breaks—to maintain their fitness for duty.

Self-care also includes "moral fitness"—defining personal values with the ability to articulate and apply values to moral challenges, especially in contested situations. This means practicing the art of seeing the world and one's situation through a lens of values, ethics, and integrity with a clear recognition of one's personal limits.

It is also important for caregivers to know that moral failure—and the distress that follows—does not have to be catastrophic and debilitating. Humans make ethical and moral mistakes, and we can recover from them. Humans have evolved with both individual and social capacities for absorbing and even growing stronger from stress—including moral stress. So if one has exercised healthy self-care and moral fitness, "leaning in" to moral stress—or stress of any kind—can make one morally resilient, stronger, and less vulnerable to the risk of moral distress and injury.

What might be the main lessons from this crisis that the health care system can use to better prepare and support caregivers for similarly stressful situations in the future?

First, our moral failures have not been limited to the health system. We, especially in the United States, have been morally shortsighted in our failure to anticipate the consequences of a global political economy that has shifted the risk (and consequences) of economic inequality, financialization, globalization, and climate change to individuals and local communities rather than providing a stronger safety net to help absorb systemic shocks. In chasing the benefits of globalization, we have abandoned and crippled our local business ecosystems and governments, rendering them powerless in responding to basic material needs in this pandemic.

As far as the health system is concerned, we have failed to build a coordinated, agile health system of guaranteed access to affordable, appropriate, and accessible care for all across jurisdictions throughout the country. We have failed to build a system that is sufficiently coordinated to ensure that essential people, equipment, and supplies are distributed seamlessly to where they are most needed. We have politicized universal health care rather than prioritizing health in all policies. This is a morally inexcusable failure.

What about the period after this crisis is over? What can be done to help caregivers deal with any trauma they might still be feeling when their lives and jobs return to some semblance of normality?

Not surprisingly, we do not have a system in place for that. Each health care system is pretty much on its own, and some systems and professions do better than others. Nursing, for example, is far more alert and responsive to the work-related stress of health care than most other clinical professions. This is another moral challenge for the health system and for society—we need a health care system that cares as effectively for its care providers as for its patients.

Posted in Health, Voices+Opinion

Tagged lindsay thompson, coronavirus