Six groups of chefs cluster at cooking stations set up in Mudd Hall, each participant wearing a tie-dyed lab coat. They have three hours to build and grill the best plant-based burger they can. Participants are nervous but excited.

Passersby ask, "What's going on?" and "What smells good?"

This is not another Food Network pilot, it's a Johns Hopkins University Intersession biology class all about fake meat.

The 17 undergrads enrolled have already attended most of the two-week course. They've absorbed instructor Eric Johnson's lectures on the whole truth about meat harvesting and the biochemistry that underlies real meat production vs. plant-based meat creation; observed tutorials on plant-based burger assemblage via YouTube; and taken a meat-cooking class at Schola in Baltimore's Mount Vernon neighborhood.

Today marks the finale, a low-stakes but fast-paced cook-off to test students' meatless recipe hypotheses. Even though the course is pass/fail like all intersession classes and even though no burger will be awarded best or worst ranking, a spirit of lighthearted competition crackles in the hall today—that and plenty of laughter.

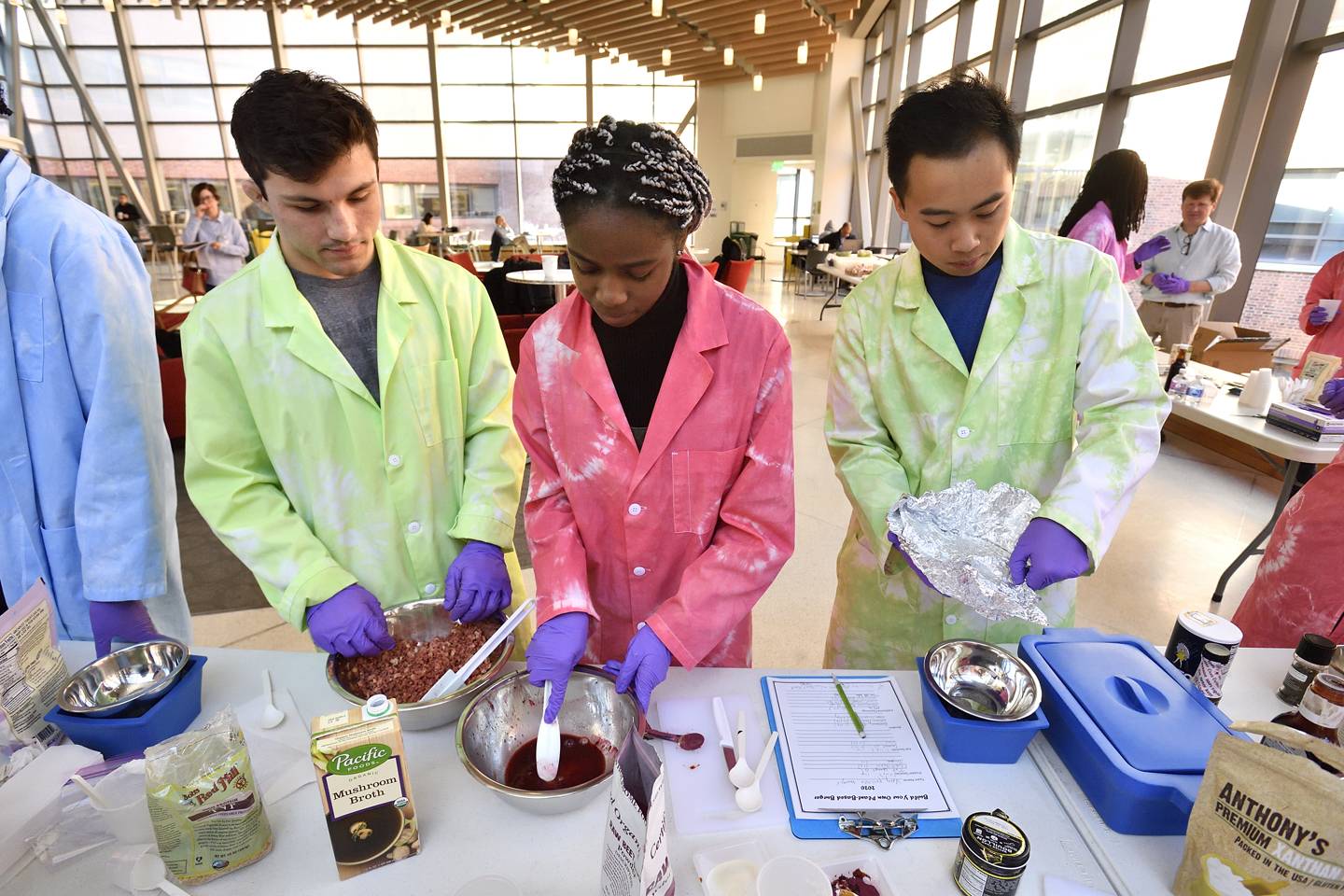

Image caption: Students were tasked with developing a recipe that uses one or more plant-based proteins, one or more binders (like xanthan gum), flavoring, fat, and beet juice to create the beef-like red coloration of meat

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"Are we allowed to modify our burger at this point [in the cooking process]?" first-year student Rose Wolkind shouts through the steam and sizzle of her professor's greasy grill-top station. She's concerned that her three-person team—they've named themselves Possible Burger—has not used enough oil or binder in their tempeh and texturized vegetable protein (TVP) patty. Why? The discs are crumbling as Johnson flips them.

Lowering his spatula, Johnson—required by a safety regulation to be the sole burger flipper—hesitates, but only briefly.

"Sure," he calls back affably, and mid-flip. (When another student asked last-minute if she could incorporate an egg, he was similarly open to the experimentation.)

A lifelong research scientist who currently directs project-based, semester-long biochemistry labs for undergrads, Johnson, 50, likes to cook for his family. He's especially adept at spaghetti carbonara. Thanks to his passion for experimentation, though, he says he never prepares the same exact recipe twice, which bugs his at-home customers.

"I'm interested in the correlations between the way we cook things and the way science is done in the laboratory," Johnson says. "This class was a great way to explore that a little bit. With the advent of all of this interest in plant-based meat, it's a perfect opportunity."

In the last couple of years, of course, consumers have become hungrier for meatless, plant-based dining options designed to save the planet—or at least reduce the meat industry's deepening carbon footprint. And while veganism has long been a trend, the typical consumer in search of a convincing plant-based burger is likely a meat eater seeking verisimilitude. Last year, in fact, the high-profile, plant-based Impossible Foods partnered with Burger King on their Impossible Whopper, now available at many of the fast food chain's outlets. McDonald's Canada cooked up a deal with Impossible Foods rival Beyond Meat last year, and Dunkin' Donuts now sells a Beyond Sausage sandwich.

To kick off the timely cooking class, Johnson provided students with several YouTube how-to videos, one featuring Celeste Holz-Schietinger, principal scientist for flavor at Impossible Foods. In the clip they watched, Holz-Schietinger preps her company's famous fake meat using water, wheat protein, potato protein, flavor broth, xanthan, coconut oil, and soybean leghemoglobin, a genetically modified, plant-based source of heme, the element that gives their "meat" its reddish color and the essential ingredient that's made Impossible a household name.

"The muscle tissue that makes up hamburger meat is chock full of myoglobin," Johnson explains. (Heme in animals is carried by hemoglobin and myoglobin.) "The supposition the Impossible Burger team is making … is that, as you cook the hamburger, the myoglobin heme are participating in the chemistries that give off the flavors and taste of cooked meat. So all of these [meat] substitutes that don't include hemoglobin will lack some unique meaty flavors."

In Johnson's class, students don't have the time or adequate resources to produce a genetically-engineered hemoglobin, but they have discussed the technique.

"We talk about hemoglobin a lot in bio," says junior Katerina Krouglicof, from team Save the Elks. "I didn't think about the cooking perspective till this class."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

For his students' purposes, Johnson has assigned a plant-based recipe equation using one or more plant-based proteins (like TVP and tempeh), one or more binders (like xanthan gum), flavoring (like MSG, vegetable broth, or dried mushrooms), fat (like ghee or coconut oil), and beet juice to create the heme-like red coloration. They've worked on recipes individually before coming together as collaborative, self-selected teams for today's cook-off.

"My personal recipe was heavily influenced by the YouTube videos we watched," says junior Emma Elias, also from Save the Elks.

Wolkin and her two Possible Burger teammates, sophomore Mitchell Kleckner and senior Nadia Crossman, have dashed back to their prep station and are tweaking their recipe with minutes to spare.

"We thought we were good on the oil," Kleckner says, breathlessly. "We were not good on the oil."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

One of the biggest hurdles today has been incorporating a plant-based fat into the patty. Plant-based fats have a lower melting point than their animal fat counterparts, which means they liquefy at temperatures at which animal fat is still solid. For pre-patty assembly, plant oils are placed on aluminum foil, frozen over 10 minutes using dry ice, crumbled, then added to a chilled protein mixture so that they don't melt when mixed.

"By crumbling the fat into the protein mixture, you can give the patty a coarseness that makes it look and feel more like meat. As the patty cooks and the water from the protein mixture evaporates, the flavor molecules get held in the patty by the oils," Johnson says. "It's the binder's job to try to keep the protein and oil together so that flavor transfer can happen."

Several of the teams' cooked patties are already waiting on plastic plates for the group taste test, which will not begin until all patties are cooked and arrayed. Many resemble small brown or tan hamburgers while some are dead ringers for taco filling.

"Ultimately, I'm aiming to incorporate ingredients from my traditional Indian Punjabi roots toward a classic American meal," says Natasha Chugh, a first-year student and member of the I Can't Believe It's Not Beef Team. "What's more, this recipe produces the perfect beef alternative for Hindus like me."

Chugh's team member Fatima Ezamzami, also a first-year, mentions that she was surprised to learn during the class's lecture on the meat industry that real beef appears darker when the animal in question died in distress.

First-year student Tomisin Longe, of the Very Possible Burger team, was similarly shocked by that factoid.

"The only reason the meat industry has considered animal treatment is financial [not ethical]," she says.

The class consists of a wide range of ages, majors, and cultural backgrounds, which is just as Johnson had hoped.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"No student has to taste anything," he points out. "A lot of people have a lot of views about meat, so I'm trying to be cognizant."

As one would expect, some students are vegetarian, some meat eaters, some a little of both. Wolkind herself keeps kosher.

"I hadn't handled raw meat," Wolkind says, referencing her beef prep class as Schola. But all students say they had already tried their hand at making some kind of patty in a pan before the course began.

"I would hope so—our moms aren't here," says junior Elizabeth Goldstone.

Over this cooking-intensive week, Johnson has urged students to make the burger they want to eat, aiming for yummy vegetarian flavor, for beefy similarity, and/or with healthfulness chiefly in mind.

Wolkind's team aimed for flavor first, and all agreed that the addition of tempeh would help matters. The We're Just Trying to Pass duo of seniors Dean Chien and Elizabeth Wu didn't add beet coloration because they didn't care about achieving a meaty look.

In the heat of the cook-off, now that Wolkind's team has added more of their binder, Johnson throws it on the grill. It holds together better. Score.

At last, it's time for the eager chefs to load their plates with plant-based sliders.

"Choose the perfect patty to be the model," Johnson says. "You can upload a pic with your summary of the process."

All, with the exception of one skeptical but grinning young man, dive in.

"I think if we made a third attempt, I would have increased the fat content and the amount of binder to maintain that burger shape," Wolkind says. But she is fairly happy with the Possible patty's flavor.

Sophomore Bradlee Lamontagne—on team Very Possible—is less pleased with his team's final product.

"I thought our burger was only barely edible—ha—which could have been fixed by having more broth and also allowing the TVP to soak in the broth longer," Lamontagne says.

As the class wraps up, there are few leftovers to be had. Even so, a couple of Mudd Hall stragglers step up for a free sample. They've been spectators for half an hour—now they want a taste.

Posted in Science+Technology, Student Life

Tagged intersession