John Irwin, a celebrated poet, critic, teacher, and editor who spent more than four decades at Johns Hopkins, died Friday after a long illness. He was 79.

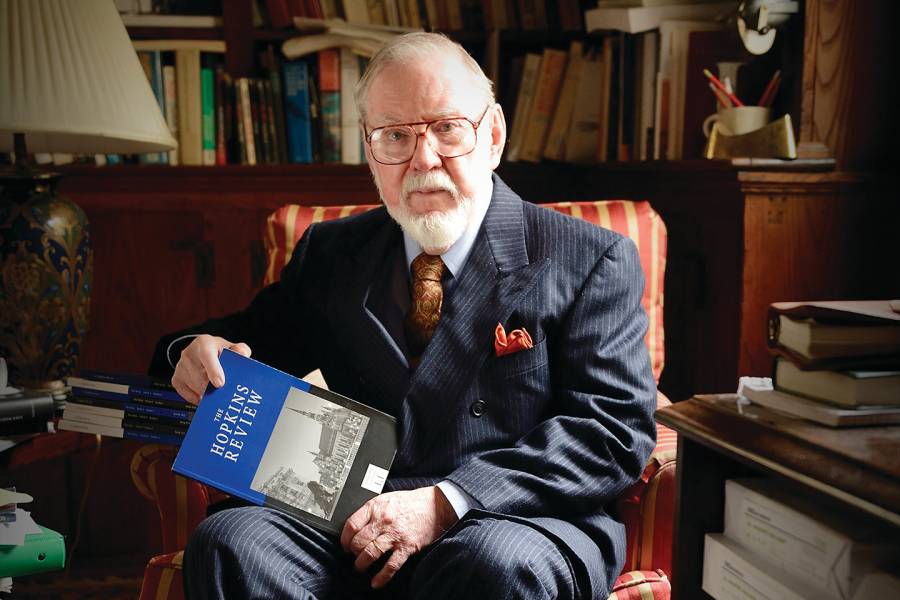

Decker Professor in the Humanities emeritus, Irwin was the author of several works of literary criticism and three volumes of poetry, including most recently As Long As It's Big (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005). He was editor of The Johns Hopkins Review from its rebirth in 2008 until 2015 and chair of the Writing Seminars for nearly 20 years. He retired from teaching in 2016.

"I feel honored to offer a few words to celebrate his luminous career as scholar, critic, teacher, poet, chairman, pillar of the humanities at Johns Hopkins, and an intellectual of a stature to compare with the greats of Gilman past," Jean McGarry, a professor in the Writing Seminars, said upon Irwin's retirement in 2016.

A modest man with a big laugh, Irwin had a photographic memory and an uncanny ability to guide students in unlocking deeper meanings in literature. Writing under the pseudonym John Bricuth, Irwin penned book-length poetic narratives noted for their unpredictability and mystery. His criticism was said to offer so thorough a reading of its subjects—most notably the modernists Faulkner, Hart Crane, Wallace Stevens, Borges, and Poe—that it answered any possible additional questions a reader might have. As an editor—both of the Hopkins Review and of the Poetry and Fiction Series of the University Press—he had a way of selecting the very best submissions in a highly collaborative and informal manner, a process that left his authors with heightened standards of their own.

Often described with words like acute, loyal, gentlemanly, and dapper, Irwin appeared the quintessential academic. But he also harbored surprises: From 1963 to 1966, he served in the U.S. Navy as communications watch officer on the staff of the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor.

His passions extended beyond literature to art, opera, food, and film. On the occasion of Irwin's retirement, his Writing Seminars colleague Brad Leithauser described Irwin's prodigious knowledge of chess, recalling a summer when he and Irwin were staying in the same villa in Florence:

"Often I, unable to sleep in the Italian summer sultriness, would play chess on the computer late into the night. My unseen opponent might likewise be in Italy, or maybe in England or America or Chile or Poland. It didn't matter where my opponent was located; this was somebody who was sharply on the attack, who was personally out to annihilate me, and who of course must be desperately fended off. John had a habit of wandering by at such times. He was about to go to bed, or maybe he'd already gone to bed, but he sensed there was a problem out there that required his urgent, discerning attention.

"He'd linger for long stretches over my shoulder—muttering, conferring, fretting and exulting by turns, and always seeking to expose to me strategic subtleties I might have overlooked. It's the distant image of John that remains most vivid in my mind, and I see now it might also serve as an image of the ideal academic colleague anywhere, anytime: somebody who peers over your shoulder and, as you contemplate making a move, gently inquires: "But have you considered this line of thought? And what about that one?"

Irwin earned a bachelor's degree in English from the University of St. Thomas in Houston, Texas, in 1962. Following his Navy service, he earned a master's degree and PhD, also in English, from Rice University. He arrived at Hopkins as assistant professor of English in 1970, leaving in 1974 to become editor of The Georgia Review at the University of Georgia. He returned to Hopkins in 1977 to become professor and chair of the Writing Seminars, and accepted a joint appointment in the English Department and an endowed chair, the Decker Professorship in the Humanities, in 1984.

He received the Helen C. Smith Memorial Award from the Texas Institute of Letters for the best book of poetry published by a Texas native or resident in 2005; was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, also in 2005; and in 1994, received both the Christian Gauss Prize from Phi Beta Kappa for the best book in the humanities and the Scaglione Prize from the Modern Language Association of America for the best book in comparative literary studies. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1991 and a Danforth Fellowship in 1962-63 and 1967-70.

He is survived by his wife of 27 years, Meme Amosso Irwin, stepsons Francesco and Stefano Saccone, and two grandchildren. His brother, William Irwin, teaches at the University of Toronto.

Posted in Arts+Culture, University News

Tagged obituaries