Thinking back to his first crossword puzzle submission to The New York Times when he was 17, Tom McCoy cringes. The theme centered on the board game Clue, he recalls.

"The theme of it wasn't very original, but the embarrassing thing was I included this word bure, a type of Fijian hut," he says, flashing a crooked smile. "I'd painted myself into a corner, but I could fill in this grid if b-u-r-e was a word. 'Oh look, it's a word.' In general, that's not how [constructing a crossword] should be."

McCoy, now 25 and a third-year graduate student in cognitive science at Johns Hopkins, speaks rapidly, with precise enunciation, as though his mouth means to keep pace with his mind.

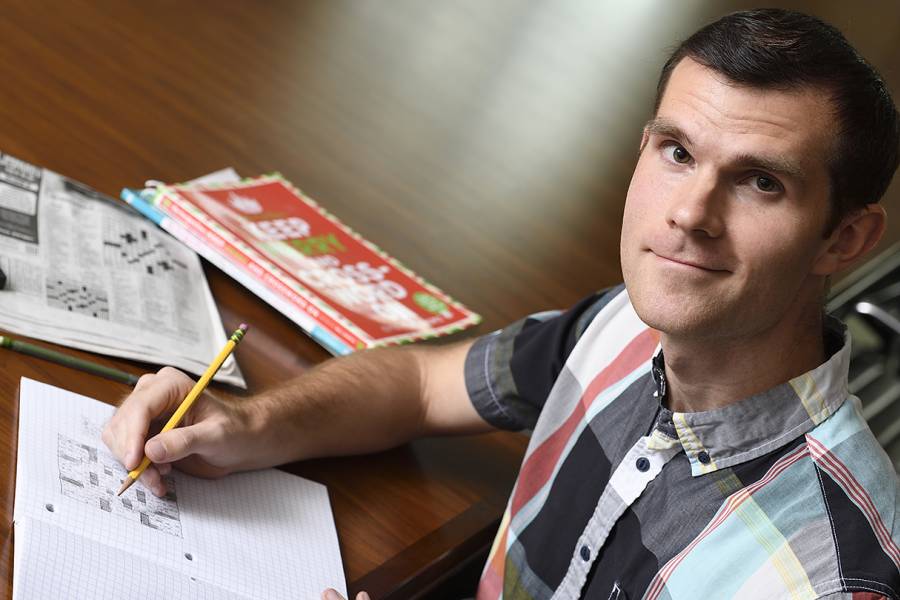

He started mapping crosswords on graph paper during his senior year at North Allegheny High School in Pittsburgh. McCoy's mom and dad—a professor of human genetics and lawyer turned educator, respectively—tested the puzzles with relish, as did his European history teacher, Mr. Mohr. McCoy submitted that first one—with clues to Clue—via snail mail to Will Shortz, cult puzzle hero and editor of the Times crossword page since 1993. Shortz rejected that early submission but encouraged young McCoy, and the teen kept going, scripting and submitting "a bundle" of puzzles in a short period. As a freshman at Yale, McCoy was thrilled to open an email acceptance from Shortz.

Video credit: Patrick Ridgely and Dave Schmelick

McCoy has since landed 33 puzzles in the Times, with two more in the editorial pipeline. His most recent, an ambitious Sunday crossword titled "Now Weight Just a Second," ran in September. The thematic concept for that crossword stemmed from one of McCoy's undergraduate classes at Yale, Introduction to Phonology.

"In English, very few words are minimal pairs for stress, which means they are pronounced exactly the same except for the way the syllables are stressed," McCoy explains. "So the [puzzle's] theme is to take a common expression and then alter the stress of one word to create a pun. So for example, you take, 'I came, I saw, I conquered,' and I change it to, 'I came, I saw, I concurred.' [The clue:] That's a description of a very easy negotiation."

To complicate—and also coordinate—matters further, McCoy says, "all the puns involved taking a word that had its first syllable stressed and changing the stress to the second syllable, like 'CON-quered to con-CURRED' or 'NO-ble to no-BEL.' Hence the title 'Now Weight Just a Second': You are 'weighting' the second syllable."

McCoy graduated from Yale with a BA in linguistics in 2017 and was awarded the prestigious Alpheus Henry Snow Prize. He chose Hopkins for grad school in part because his adviser, Robert Frank—formerly a professor in JHU's Department of Cognitive Science—had so much praise for his former department. McCoy also liked the campus and felt an easy familiarity with Baltimore, his father's hometown. During McCoy's childhood, he and his four sisters stayed with their paternal grandparents in the summers for day camp stints at the Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth. He attended an annual New Year's Eve family dinner at the Johns Hopkins Club, organized by his grandmother, Martha McCoy, who received a Certificate of Advanced Graduate Study in Education from Hopkins in 1976.

Education clearly remains top priority in the large family—McCoy's sisters, ages 22 to 32, all have impressive expertise in areas of biology.

"I'm a black sheep in that way," McCoy notes.

He'll often conjure things his sisters or parents have told him or taught him when writing his crosswords. For a competitive crossword constructor, the more well-rounded knowledge about anything and everything, the better—and a sense of humor helps, too.

"I was texting my sister, who was taking the ACT, and she was saying that the instructions were really confusing," McCoy says. "So I remember texting a joke to her: 'Sounds like that was a tough ACT to follow.'"

McCoy began to consider other acronyms, like MIA, which slides nicely into the phrase, "Mamma MIA," and another New York Times crossword was born.

"Something linguists and crossword constructors have in common: There's always part of your brain analyzing every piece of language you encounter," he says.

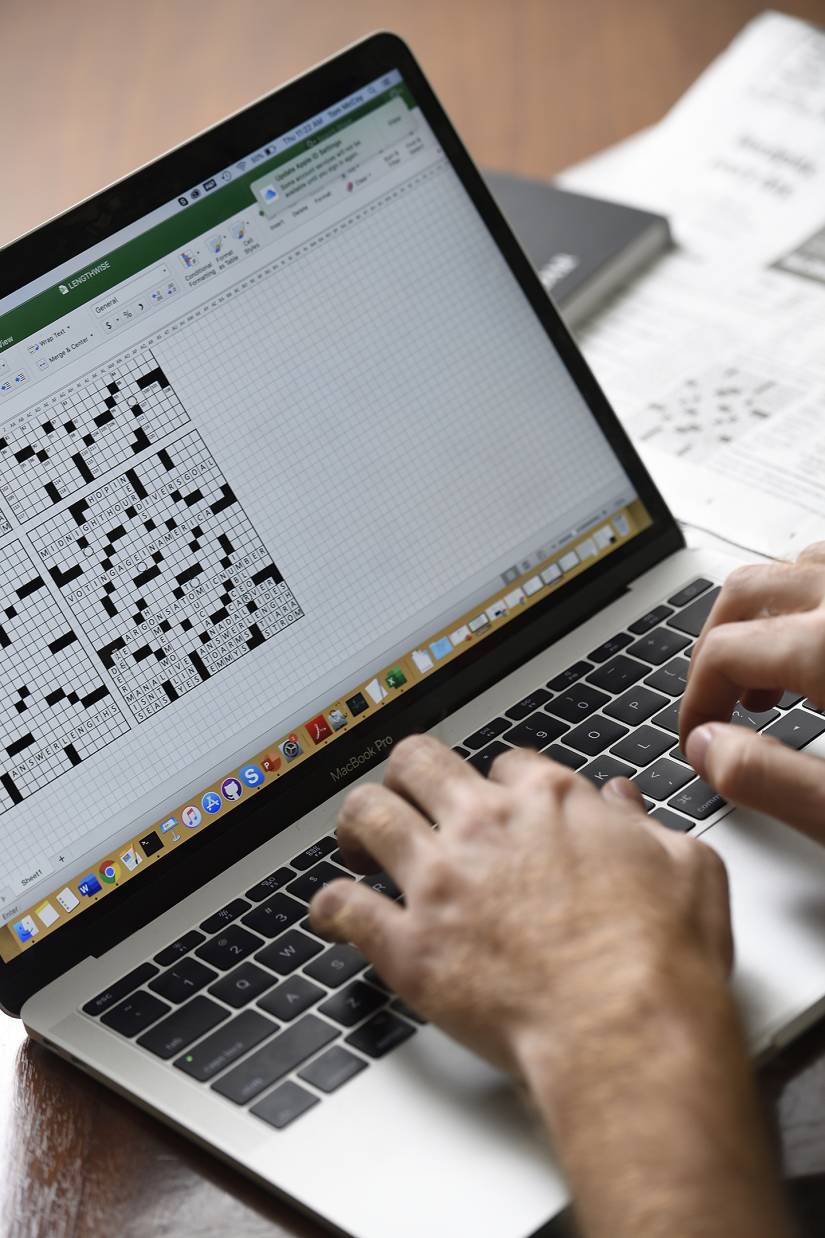

Image caption: Although McCoy began his crossword career by drawing crossword puzzles on graph paper, his go-to these days involves drafting puzzles using spreadsheet software.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

McCoy decided to transition from linguistics into cognitive science to further broaden his academic horizons.

"I focus on computational linguistics, which is trying to model the structure of language with computers," he says. "How on earth is this really complex mathlike system encoded in our brain?"

While anyone may submit a crossword to The New York Times, it takes a savvy constructor to land even a weekday puzzle in the paper, let alone a more advanced Thursday, Friday, Saturday, or Sunday construction, the last of which may include up to 140 words. On average, even an uber thinker like McCoy spends anywhere from 40 to 80 hours constructing a single puzzle. He has about a 50% acceptance rate at the Times. When a puzzle is rejected, it's no biggie, though—he moves on to another.

"It's really just a fun hobby," he says.

A pursuit that's fun to McCoy, however, leaves many hopefuls stumped. The newspaper receives more than 125 crossword submissions weekly.

"[Some] try for years and years and never get a single puzzle accepted," Shortz says. "First, we consider the theme: Is it consistent, is it understandable, is it fresh … engaging? Then we look at the quality of the fill [those more numerous answers unrelated to the theme]. We want interesting, colorful, lively vocabulary that ideally hasn't been used a lot before, with as little crosswordese and stupid obscurity as possible."

Shortz says that good clue writing is underrated—he and his two editorial assistants, one of whom holds a cognitive science degree, do not accept or reject puzzles based on the quality of the contributors' clues.

"If we like the theme and the fill, we know we can write the clues ourselves," Shortz says. "But it's nice to get a manuscript that's pretty good. Tom is pretty good himself."

While McCoy spends the majority of his time on his studies, he works on a puzzle whenever he has the chance, like a long holiday from school—always for the sheer fun and daring. One of his own all-time favorites was another Sunday Times puzzle he constructed, this one published in 2014. The title, "We Hold These Truths to Be Self-Evident," featured self-evident or tautological expressions.

"It ain't over till it's over; it is what it is; boys will be boys; haters gonna hate," McCoy says, laughing. "I was proud to be the first person to use 'haters gonna hate' in The New York Times crossword."

McCoy and Shortz have met in person at the American Crossword Tournament hosted annually by Shortz in Stamford, Connecticut, and the subject of the 2007 documentary Wordplay.

"There's a big cadre now of younger, under-30 constructors; we hang out there [at the tournament]," McCoy says, noting that his graduate study has prevented his attendance of late.

Though Shortz is well known among the crossword crowd as a lifelong puzzle devotee, he says it's the puzzle enthusiasts that he enjoys most of all.

"People like Tom who are smart, interesting people with lively minds, they know a little about everything," Shortz says. "It's nice to deal with them through email, but it's wonderful to meet them as well."

Having finished his coursework last year, McCoy now spends much of his time conducting research—writing code and running experiments on computers—and currently serves as a teaching assistant to his Hopkins adviser, Tal Linzen. Professor Paul Smolensky is McCoy's co-adviser. McCoy says he especially appreciates the fluid integration between disciplines within graduate specializations at JHU.

"It's so supportive in terms of interdisciplinary work," he says. "My interests really do lie at the center of linguistics and computer science. A lot of schools have a great linguistics department and great computer science department but don't get much interaction across these areas, whereas here there's a great group of linguists in my own department and great scientists in computer science who talk and publish papers together."

He also admires the intellectual diversity of the undergraduates with whom he works.

"We get students from a wide variety of backgrounds—cognitive science, computer science, psychology, literature, math—so when a student comes to me with questions, I'll have to think about the best way to answer it given their background," McCoy says. "I think it's valuable for me to consider my field from all these different perspectives because cognitive science is an inherently interdisciplinary field that benefits greatly from the diversity of the people who study it."

Posted in Student Life

Tagged cognitive science, thank you video