Stephen Dixon, a prolific powerhouse of an author and retired professor in The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University, died Wednesday of pneumonia and complications from Parkinson's disease at Gilchrist hospice center in Towson. He was 83.

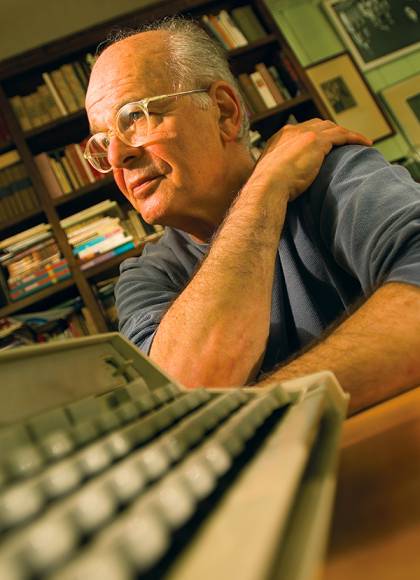

Known for developing very human characters while experimenting—sometimes wildly—with various forms of storytelling, Dixon wrote 17 novels and more than 500 short stories, several of which were adapted into film. He built his body of work by completing at least one finished page per day on his Hermes Standard typewriter. His stories blend truth and fiction, multiple versions of one event, and one time period with another, all glued together with humor, tragedy, sex, anger, cruelty, and dishonesty, often in exceptionally long sentences and paragraphs. Absorbing his work is an art in itself; in 2007, he told The Baltimore Sun, "I teach my readers how to read my work while they're reading it."

A popular teacher, he was generous with his time and his feedback, influencing during his 26 years as a member of the Johns Hopkins faculty countless successful writers, including Jean McGarry, Michael Kun, and Ben McGrath. His critiques were thoughtful and extensive, rooted in his belief that every piece had groundbreaking potential.

"He was my absolute favorite writer who became my greatest mentor," says Porochista Khakpour, MA '03, herself now a celebrated writer and teacher. "I learned more from him than any writer I've ever met. He continues to be the single greatest influence on my work, and I have his voice in my head with everything I write."

Dixon was the winner of four O. Henry awards for fiction, two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, two Pushcart Prizes, the American Academy Institute of Arts and Letters Prize for Fiction, and a Guggenheim fellowship. He was twice a National Book Award finalist, in 1991 and 2001, and was also a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction in 1992 for his novel Frog.

"It's hard to believe such a force of nature as Steve Dixon could be gone. His love of writing was only exceeded by his love of his family: his late wife, Anne Frydman, and daughters, Sophia and Antonia," says McGarry, professor in The Writing Seminars. "He was a pillar of the fiction program in The Writing Seminars. Widely read, he was a fierce critic, admiring mostly stylistic originals like Samuel Beckett and Thomas Bernhard. And yet, he was generous and encouraging to young writers, and seemed to believe that he could teach anyone to write well.

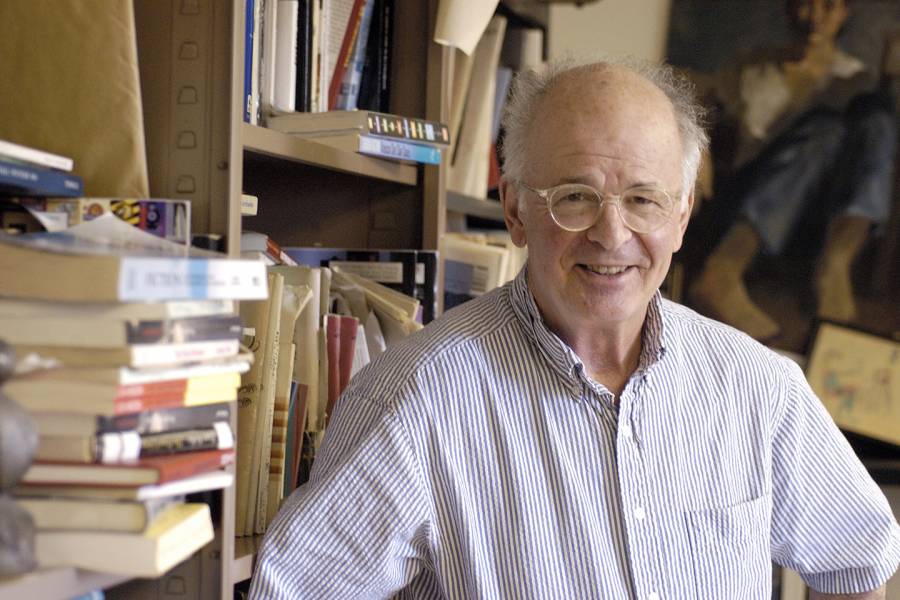

Image caption: Stephen Dixon came to Johns Hopkins in 1980 as an assistant professor in The Writing Seminars and remained on faculty until his retirement in 2007.

"Absent of even a glimmer of vanity, Steve, according to his wife, had two outfits: in summer, shorts and a t-shirt; in winter, sweat pants and sweatshirt. Getting to his desk, and his typewriter, was the objective of every single day.

"I will miss him. He was a true original as a writer, a husband, a father, a friend, a man."

Khakpour said she came to Hopkins because of Dixon, in appreciation of his New York hyperrealism and his Modernism.

"He permanently alters how you approach storytelling; you realize it's first and foremost about syntax and diction," she says. "To me, he was such a true artist. It reminds me to think about art first and to have integrity as writer; he never made the big bucks. His writing was extremely personal: We were all there, his students and his late wife. He didn't distinguish between life and art. You just don't get those writers anymore. It's the end of era for me with his passing.

"He was a ferocious lion of a man in every meaning of that word. A giant, but so tender and soft. He was incredibly contrarian, irascible, and difficult in a beautiful way you had to honor. And he was always right; it was infuriating."

Born Stephen Ditchik, he grew up on New York's Lower East Side. His mother changed the family last name after his dentist father was imprisoned in 1941 in connection with a physician who was performing illegal abortions. He earned a bachelor's degree in 1958 from City College of New York in international relations, and took a job as a radio reporter in Washington, D.C., where he began writing fiction on a whim. He described the new experience as ecstatic, and wrote just about every day thereafter.

His first story, "The Chess House," appeared in The Paris Review in 1963. He went on to work as a school teacher, artist's model, cabdriver, salesclerk, and bartender, among other jobs, continuing to publish stories and, in 1976, his first novel. In 1980, then-Writing Seminars chair John Irwin hired Dixon as assistant professor. He was named professor in 1989, and retired from the position in 2007.

As much as influencing his students' writing, Dixon influenced the way they came to carry themselves as writers.

"He was not what I'd expected," says John Barry, MA '01, recalling his entry into The Writing Seminars. "A quick read through Frog had led me to expect a French-looking guy in a beanie—but when I arrived I found an over-six foot, balding guy wearing grandma jeans.

"He drove me to work hard by example: he was a writer who had, more than anything, trust in the craft itself—even when it didn't seem to be bearing fruit, he pushed us to ride out the waves. Writers aren't always known for their cheerfulness, but he radiated a sense that we were lucky to be doing this, that engaging in the process was a gift itself. It sounds bland, but he was a truly good guy, and a teacher of rare generosity who taught writing as integrity: commitment to the truth, wherever it takes us."

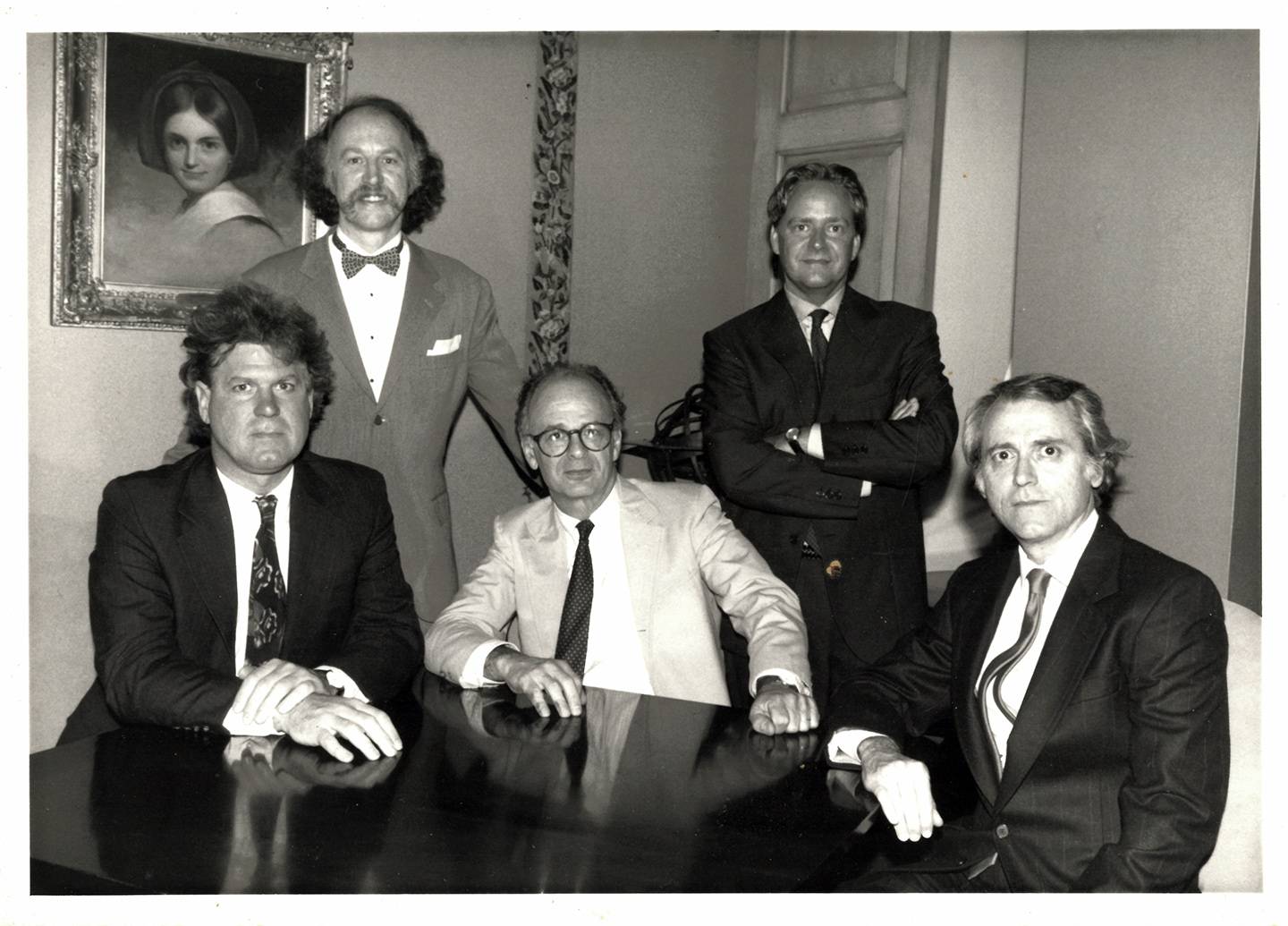

Image caption: Stephen Dixon (center) was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction in 1992 for his novel Frog, along with Paul Gervais, Allan Gurganus, Bradford Morrow, and Don DeLillo.

Dixon's former students speak fondly of the personal touch inherent in their very first encounter with him: their offer of admissions to The Writing Seminars master's program, made over the phone. For Betsy Boyd, MA '03, that call made all the difference in her decision to attend Hopkins.

"He's the one who called me to tell me I'd been accepted to Hopkins, and it was a thrill to hear his warm voice and learn the great news straight from a Hopkins professor's mouth. He was easily conversational on the phone, not in a rush," says Boyd, who today—as director of the creative writing program at the University of Baltimore—makes an effort to contact potential students the same way.

"That same easy and gentle vibe held true when we worked together in the classroom," Boyd adds. "Steve was an encouraging teacher who wanted students to succeed. He was a down-to-earth instructor, a fine line editor, who would make lots of small sentence-level notes and sometimes little drawings all over the story at hand."

Writer Jessica Anya Blau, MA '95, also recalls her first encounter with Dixon—this one at the cocktail party for incoming Writing Seminars students—for the way it set the tone for a quarter-century friendship. "There were two things that struck me about him from the start: he didn't engage in pointless small talk, and he was utterly genuine," she says.

"Steve felt familiar, like someone I was related to—I think that's what it's like when someone is utterly himself. In the 25 years that have since passed, Steve was never anything less than that. He was a true friend, a dear friend, a true person, and an inspiration to me. I love his work. And I loved him, his wife, and the girls, too."

Posted in Arts+Culture, University News

Tagged writing seminars, obituaries