Every person, at some point, has experienced a moment of feeling excluded, overlooked, or unappreciated. But even in these moments of isolation, one thing unites us: Our ability to remember these painful experiences of exclusion in almost perfect detail.

According to Kristopher Bell, head of talent development at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab and a leadership coach certified by the NeuroLeadership Institute, the reason we remember so much about these instances is because of the way our brains process memories and social trauma.

During his presentation, "Building an Inclusive Culture: One Brain at a Time," delivered during Johns Hopkins University's 16th annual Diversity and Inclusion Conference on Friday, Bell described the biology of the human brain as it relates to forming and reinforcing biases. He also provided guidance for how to make others feel supported.

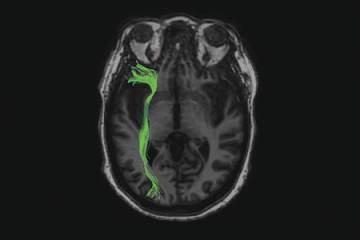

In the brain, he explained, emotions are processed in the amygdala, and the hippocampus sorts and stores memories. According to Bell, during a traumatic event, the amygdala is triggered and signals to the hippocampus that a memory is important. It's because of this relationship that we have such a clear recollection of significant tragedies, but also of personal slights and hurts as well.

Additionally, our brain contains four times more real estate for identifying threats as it does for processing rewards. Because of this, microaggressions and perceived inequalities can have a major impact on our relationships with others. Social pain is processed along the same pathways as physical pain—to the point, Bell said, that aspirin has been found to be as effective at easing emotional pain as it is at relieving a headache. Because of this, he emphasized the importance of active support of others.

Image caption: Attendees discuss topics during "Building an Inclusive Culture: One Brain at a Time" workshop at the Diversity and Inclusion Conference.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

During the workshop, Bell also described the brain's use of schemas—or mental maps—and the ways they can contribute to the formation and perpetuation of biases.

According to Bell, recent research suggests that the brain functions primarily as a pattern-recognition machine. When exposed to a new experience or information, the cortex—which serves as the logical part of the brain—analyzes prior experiences or knowledge to see if the new experience can be partnered and added to an existing schema.

A schema pairs like sets of information together, supporting and reinforcing the knowledge that can then be stored together. The greater hippocampal connectivity there is when encoding a schema, the stronger the memory or belief that is formed. While this works well for many sets of information, Bell said there is a danger that the formation of schemas can reinforce socially learned biases.

"If something comes into our brain that we don't understand automatically, it may try to attach it to a schema even if it doesn't fit," Bell said. "If that same occurrence then happens once or twice more, it might emphasize our prejudices."

While it's impossible (and also inadvisable) to stop the brain from forming these schemas, understanding how they are formed can create its own mental map in the brain, one that has the potential to recognize confirmation bias.

The workshop concluded with an overview of the SCARF model, developed by neuroscientist David Rock and used among APL's leadership. SCARF refers to five aspects of interpersonal relationships that can trigger the threat/reward centers of the brain: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness.

The model encourages reflection on how our interactions with others may trigger threat responses in these five categories and the ways they can be reframed to provide a sense of inclusiveness.

Cathie Axe, the university's executive director for Student Disability Services, said she was interested in the neurodiversity aspects of the talk and the SCARF model, noting that its important to tailor our interactions to individuals.

"We are all so unique in the way we process information, and we have a tendency to try and figure out what's normal, when we're much better off thinking expansively about how to be inclusive of all of our variability," Axe said.

Sponsored by the Diversity Leadership Council, the Diversity and Inclusion Conference has been held annually on the Homewood campus since 2004. This year's conference featured 20 workshops and a presentation by Maria Hinojosa, anchor and executive producer of PBS' America by the Numbers with Maria Hinojosa.

Posted in Science+Technology, University News

Tagged diversity leadership council