Professor Richard A. Macksey says "a lack of focus" is his most defining characteristic. He is known to wander sometimes during a conversation, has a habit of being in the middle of several books at one time and is certainly hard to pin down to a straight answer. One former student says that asking Macksey a question is like going to a fire hydrant for a drink of water.

For instance, ask him what he does for a living, and he'll tell you indirectly he is a teacher. "Oh. What do you teach?" you may inquire.

"My wife gets very impatient with me when I try to explain this," Macksey says before he goes off into a several-minute explanation. "I guess it also depends on what day and what hour you ask me the question."

Indeed, Macksey's areas of interest range from classical literature and foreign films to comic novels and medical narratives—all subjects he has taught at one time or another.

Even when given a more benign question—such as "where are you from originally?"—Macksey still manages, in his charismatic way, to elude a short, pat answer.

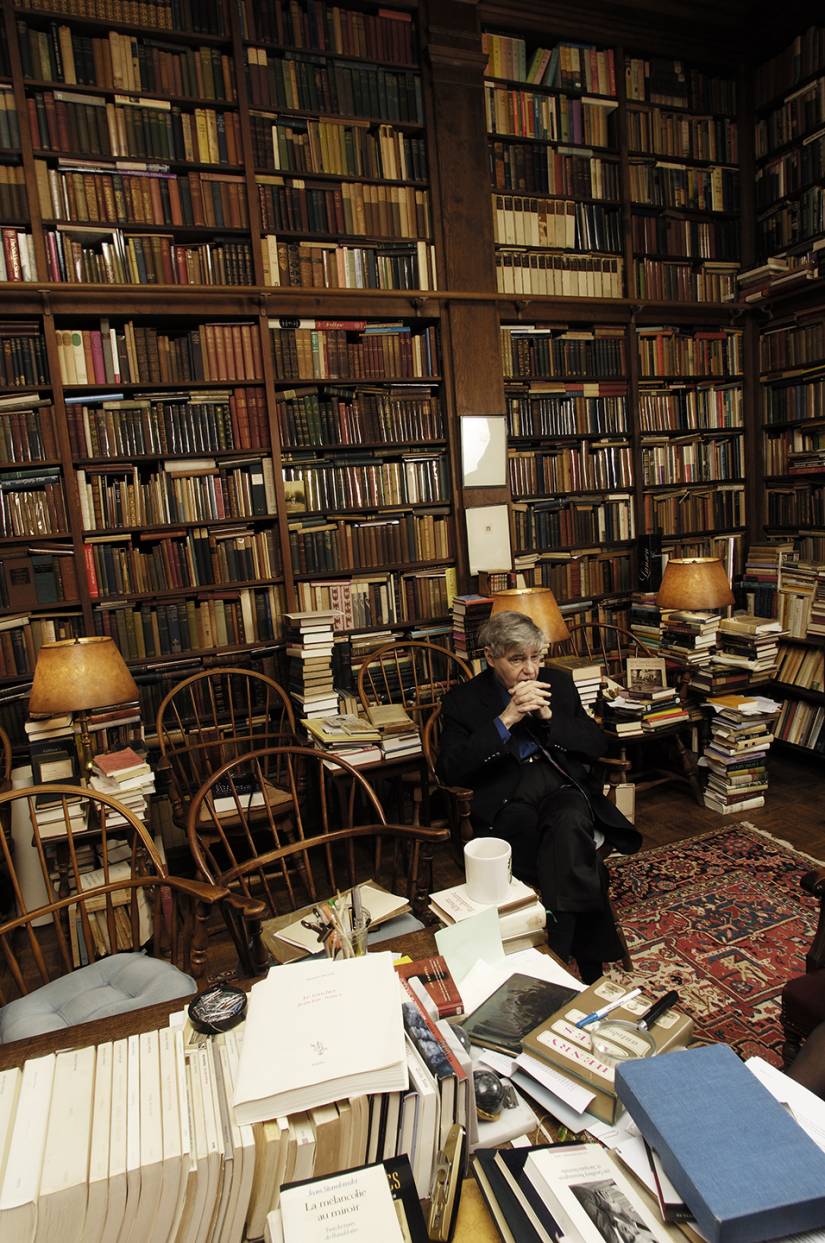

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"I was born in a delivery room that was half in Glen Ridge and half in Montclair, N.J., so I have birth certificates from both towns," says Macksey, a professor with appointments in both the School of Arts and Sciences and the School of Medicine, where he is co-director of the humanities programs. "You could say I was born in two places at once. But they are so alike, you wouldn't notice the difference."

Yet for an individual with such "a lack of focus," as he calls it, he certainly has managed to accomplish a great many things.

Macksey began his Hopkins teaching career in the fall of 1958, when he received his first appointment as an assistant professor in the Writing Seminars. Since then Macksey has introduced a slew of innovative courses to the School of Arts and Sciences; has published fiction, poetry, translations, and a wide spectrum of academic works; edited journals; helped to found the Humanities Center; and become a much beloved and respected teacher. [Editor's note: The Humanities Center is now the Department of Comparative Thought and Literature].

Macksey was honored for his teaching ability in 1992, when he received the university's George E. Owen Teaching Award, given annually for outstanding teaching and devotion to undergraduates. A few months ago he was recognized for his remarkable career when the Johns Hopkins Alumni Association bestowed on him its Distinguished Alumni Award.

And on May 26 he was honored yet again, at the dedication ceremony for the Richard A. Macksey Professorship for Distinguished Teaching in the Humanities. This piece of academic immortality was bestowed upon him by a Hopkins alumnus and one of Macksey's former students, Edward T. Dangel III, who along with his wife, Bonni Widdoes, endowed the professorship.

For those who know Macksey, this latest honor is a much-deserved and fitting tribute to an innovative teacher.

"When Hopkins alums think of the humanities, they think of Richard Macksey. He has been teaching large, interesting, and varied courses for decades, and he has always had time to talk with all sorts of students about what they were studying, reading, and thinking about," says Neil Hertz, a professor of English and director of the Humanities Center. "It's worth stressing his remarkable generosity of his time, his intellectual energy, and his enormous stock of knowledge."

A polymath who can read and write in six languages, Macksey gives the impression that his mind is juggling a million things at once. Hertz likens Macksey's thought process to a chain reaction.

"The man's right, he lacks focus—one thing leads him to another, and that in turn leads to a third. And, given his astonishing memory, to a fourth, a fifth, and so on," Hertz says. "This could be a real drag if, say, you rolled down the window of your car at a traffic light to ask Dick directions to some place, while cars behind you began honking 1/25th of the way through his rambling, but no doubt interesting, answer.

"On the other hand," Hertz adds, "if you are doing interdisciplinary work, an ability to link one thing to another is a positive asset."

Macksey was, however, focused at one time—on a career in medicine, deciding as a boy that he was going to become a doctor.

"You needed a profession, and we didn't have any medical people in my family, so I said, sure, I'm going into medicine," Macksey says. "It got adults off your back when you said you were going to study medicine. And then I gradually realized that it was a way to give meaning to your life—or at least to make a plausible story."

His assurance began to wane slightly, however, when he took a job during high school as a hospital orderly.

"I was fascinated by the human dimensions of the experience, but I didn't have the temperament of a real clinician," Macksey says. "Yet I still found the study intriguing. You can postpone a medical career for quite a while if you are interested in research. Biophysics, for instance, was an exciting new prospect with enormous implications for medicine. Then, thanks to a great teacher, I got interested in math and published a bit. Overall, my non-career in the sciences was something that helped to open my mind. While I lacked the drive and focus that made a great scientist, I had enough interest to learn some habits of inquiry that may have helped me as a teacher."

It was while studying science that Macksey's interest and attention began to drift toward literature—something more akin to a seduction, he says.

He eventually decided to concentrate on the written word and chose to come to Hopkins in 1953 to enter the Writing Seminars. He then went on to earn a doctorate in comparative literature from the university in 1957, writing a study in French on Proust. While he was compiling the dissertation, he took a teaching position at Loyola College. A year after the degree, Hopkins beckoned his return.

The first classes he taught in the Writing Seminars were writing workshops and something called "modern writers," but it didn't take long for Macksey to think about expanding students' horizons.

Wanting to introduce a film course, he persuaded the dean of what was then the Evening College to sponsor it and allow Arts and Sciences students to attend without charge. This led to some impromptu production workshops in the Seminars. Later, with the help of colleagues and students, he initiated the first courses at Hopkins on African-American literature, women's studies, scholarly publishing, and an interdisciplinary program. Throughout his career Macksey has had a habit of filling what he perceives as holes in the curriculum. To that end, in the 1960s he played a large role in the creation of the Humanities Center, an interdisciplinary incubator that sponsors courses in literature, art, philosophy, and history.

"It was a place where we could try out new curricular ideas and explore recent intellectual developments without a massive infusion of cash and administration," Macksey says. "You can test concepts in the humanities and see if they fly, as in a lab, though the standards of proof are different. All of this would have been impossible without the active participation of our neighboring departments and the great influx of energy brought by our visitors from overseas.

"In its best seasons," Macksey adds, "Hopkins has always been hospitable to these interdisciplinary experiments. If the initiatives prove promising, the powers can later find a more permanent home for the most deserving cases."

Speaking of home, Macksey sometimes teaches from his.

Jean McGarry, chair of the Writing Seminars, fondly recalls the course she took at his Guilford residence.

"It was a course on the ironic narrative, and he taught it in the form of an ironic narrative. I mean, the form of the class was the content of the class. It was an amazing piece of ingenuity," McGarry says.

McGarry also remembers Macksey's way of interjecting various works of literature into his lectures. He made them sound so appealing and interesting, she says, that she just had to write their names down.

"I had my reading list for the next 10 years lined up," McGarry says.

Macksey had always been well read. Even as a teenager, when other kids his age were fumbling in the backs of cars, he says, he was off reading the likes of Spengler and Chekhov. That love of books has continued throughout his life.

A well-documented bibliophile, Macksey lives in a house that is literally submerged in books. It is hard to travel more than a few feet in any direction without running into a bookshelf of some sort. Then there is his actual library, two rooms of wall-to-wall volumes ranging from the classics to recent fiction. It is in this library, which doubles as a projection room, that Macksey teaches some of his courses.

He hasn't read—"yet"—all the books he owns, but, according to some colleagues, he must have at least a couple of thousand volumes stored somewhere in his head.

Dangel, the professorship's donor, recalls his amazement at the level of knowledge his young professor had.

"When I first met him, he was just 29 years old. And even then he knew, and had read, everything," says Dangel, who took several of Macksey's courses during a two-year period from 1962 to 1964 and is now a practicing attorney. "He is extraordinarily brilliant. He just understands so much."

Dangel adds that some students are daunted at first by Macksey's lectures.

"I didn't understand a thing he said for the first five weeks, and then, all of a sudden, it hit me. It was like learning by osmosis. He'll be talking, and then it just sinks into you. When you start to catch on to what he is saying, you remember what he said, and it all makes perfect sense. Not a whole lot of teachers can have an effect on students that way."

Dangel says he and his wife have endowed this chair in appreciation of Macksey's special abilities, in particular those as a teacher.

"I think this is a great research institution that ought to sponsor great teaching as well," Dangel says. "Whenever I read an interesting novel, I remember my time with him, and it enhances my enjoyment of the book. And he taught me how to organize and communicate a story, something that I use all the time as a trial lawyer. He just embodies the humanities."

The holder of the Macksey Professorship will be recommended by the dean of the School of Arts and Sciences and approved by the university board of trustees.

Macksey himself will not hold the position.

Herbert L. Kessler, dean of Arts and Sciences, says the chair will be held by someone who has distinguished him or herself as a teacher of narrative forms in the humanities, such as film studies or fiction writing.

"This is a high distinction. Named chairs are awarded to people who in principle are extremely distinguished in the field," says Kessler, who expects to announce the first appointment soon.

Receiving such a lasting honor as this, Macksey says, is a bit overwhelming.

"It is a little daunting to join the exalted ranks of Breuer, Eames, Le Corbusier, and Mies, who have chairs named for them," Macksey says wryly. "But I do not want the occasion to pass without saluting Terry [Dangel] and Bonni [Widdoes], not only for their generosity but also for the characteristically imaginative way in which they have conceived their gift."

At the dedication ceremony for the professorship—attended by more than 200 faculty, administration, and former Macksey students—Macksey was given a first-edition Chinese translation of one of his favorite books, James Joyce's Ulysses.

The translator started the work late in life and didn't finish it until he was in his 80s.

Commented one of the ceremony's speakers, "Now that is the kind of guy who belongs in Macksey's library."

Posted in University News

Tagged obituaries, humanities