- Name

- Barbara Benham

- bbenham1@jhu.edu

A study led by researchers at the International Vaccine Access Center at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health has found that respiratory syncytial virus and other viruses appear to be the main causes of severe childhood pneumonia in low- and middle-income countries, highlighting the need for vaccines against these pathogens.

While much progress has been made to reduce childhood pneumonia, it remains the leading cause of death worldwide among children under 5 years old, with about 900,000 fatalities and more than 100 million reported cases each year. This makes pneumonia a greater cause of childhood mortality than malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, Zika virus, and Ebola virus combined.

The study, published today in The Lancet, was the largest and most comprehensive of its kind since the 1980s. The study—called the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health, or PERCH, study—included nearly 10,000 children in Bangladesh, The Gambia, Kenya, Mali, South Africa, Thailand, and Zambia. It was led by Katherine O'Brien, a professor in the Department of International Health who at the time of the study served as executive director for the Bloomberg School's International Vaccine Access Center. She is now director of Immunizations, Vaccines, and Biologicals at the World Health Organization.

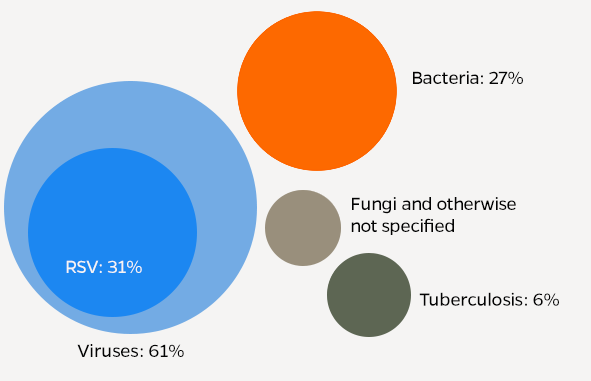

After testing for viruses, bacteria, and fungi in children with severe hospitalized pneumonia—and in community children without pneumonia—the study found that 61% of severe pneumonia cases were caused by viruses, and that Respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, alone accounted for 31% of cases. Other top causes were rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza viruses, and S. pneumoniae bacteria.

"Prior to this study, we didn't know which specific viruses and bacteria are now causing most of the severe childhood pneumonia cases in the world, but public health organizations and vaccine manufacturers really need that information to work toward reducing the substantial childhood mortality that pneumonia still causes," says study co-principal investigator Maria Deloria Knoll, a senior scientist in the Bloomberg School's Department of International Health and associate director of science at the International Vaccine Access Center.

For their study, researchers took nasal and throat swabs as well as blood, sputum, and other fluid samples from 4,232 children under the age of 5 with cases of severe hospitalized pneumonia and from 5,325 community children without pneumonia during a two-year period. They tested the samples for pathogens using state-of-the-art laboratory techniques. Cases for the primary analysis were limited to those whose pneumonia was confirmed by chest X-ray, and children with HIV were considered in a separate analysis because the causes of their pneumonia would likely differ from those without HIV. With analytic methods unique for an etiology study, the researchers compared the pathogens found in samples from severe pneumonia cases to those from other children in the community in order to estimate the likeliest cause of each case. In this way they were able to identify the leading causes of childhood pneumonia among children in these settings.

The researchers concluded that, across all study sites combined, viruses accounted for 61.4 percent of cases, bacteria for 27.3 percent of cases, Mycobacterium tuberculosis for 5.9 percent of cases. Fungal and unknown causes accounted for the remainder of cases.

"We now have a much better idea of which new vaccines would have the most impact in terms of reducing illness and mortality from childhood pneumonia in these countries," says O'Brien.

PERCH estimated that RSV was the leading cause of severe pneumonia in each of the seven countries studied. The virus has long been known as a common and potentially serious respiratory germ among children and the elderly, and several RSV vaccine candidates are being developed and evaluated in clinical trials. A monoclonal antibody therapy, palivizumab, is available for the prevention of RSV disease in children with underlying medical conditions but is not suitable programmatically or financially for widespread use in routine immunization programs.

Identifying the germs that cause pneumonia is difficult in individual cases under the best circumstances. But it's far more difficult in low- and middle-income countries where most pneumonia deaths occur, where the analysis has to take place on a scale of thousands of cases. Researchers in prior pneumonia studies simply lacked the microbiological and analytical resources to produce estimates of the major pneumonia pathogens, Knoll says. And, in the past two decades, many low- and middle-income countries have introduced effective vaccines against known major bacterial causes of pneumonia—Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae—so the global mix of pathogens causing childhood pneumonia has changed as a result.

To address this difficulty, PERCH developed a new analytic tool to combine evidence from multiple test results to estimate the causes of pneumonia. The analytical technique is called the Bayesian Analysis Kit for Etiology Research, or BAKER, and is available online as an open-source application for use by other public health researchers.

"Estimating the etiology of pneumonia was like a complex jigsaw puzzle where the picture could only be seen clearly by assembling multiple, different pieces of information using innovative epidemiologic and statistical methods," says Scott Zeger, a professor in the Bloomberg School's Department of Biostatistics.

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged global health, vaccines, infectious disease