When it first began six decades ago, the Johns Hopkins Tutorial Project was associated with a kind of radical, activist spirit. That was largely because its founding father, celebrated university chaplain Chester Wickwire, devoted his career to promoting social justice, long before it was the popular issue it is now.

During the 1958-59 school year, Wickwire sent Hopkins undergraduate students, then mostly white and male, out to tutor in neighborhoods of a deeply segregated Baltimore. By the mid '60s, his formalized project had hundreds of volunteers tutoring local elementary-schoolers on the university's Homewood campus.

With its origins in the civil rights era, the Tutorial Project is one of the oldest and longest-running campus tutoring programs in the country. It's also one of the most consistently popular extracurriculars at Johns Hopkins, and for many, a defining experience of their undergraduate life.

"It always surprises me, because this is a significant time commitment—four hours a week—but every semester we have to turn people away," says Emma Maxwell, a senior who serves as a student leader for the program.

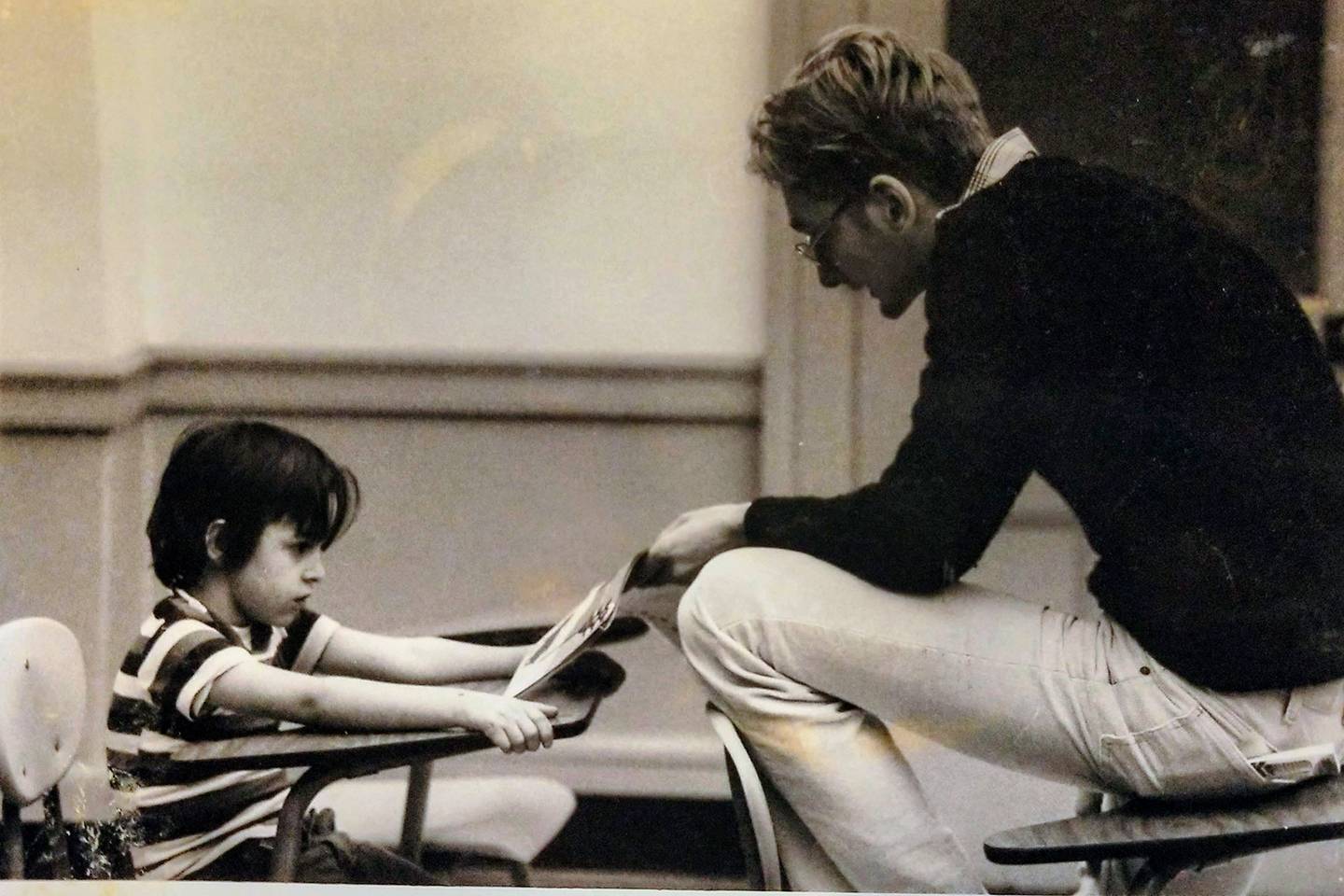

Image caption: A Tutorial Project volunteer works with an elementary-schooler on how to tell time on an analog clock.

Image credit: Courtesy of Young Song

Young Song, the director of the Tutorial Project for the past 12 years, can recall cases where volunteers have changed their academic or career directions based on their tutoring experiences, from law to education, for example.

This spring, 130 Hopkins undergrads have been paired with an equal number of Baltimore elementary-schoolers, according to Song. The twice-weekly afternoon tutoring sessions focus on improving the kids' math and reading skills.

"This year, we had a fifth-grader who entered reading below grade level, and now he's reading [the award-winning young adult novel] The Hate U Give," Song says.

As part of Alumni Weekend, the Tutorial Project will host a brunch to celebrate its 60th anniversary. The event, which takes place 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Sunday in the Glass Pavilion of Levering Hall, will include speeches from two former volunteers.

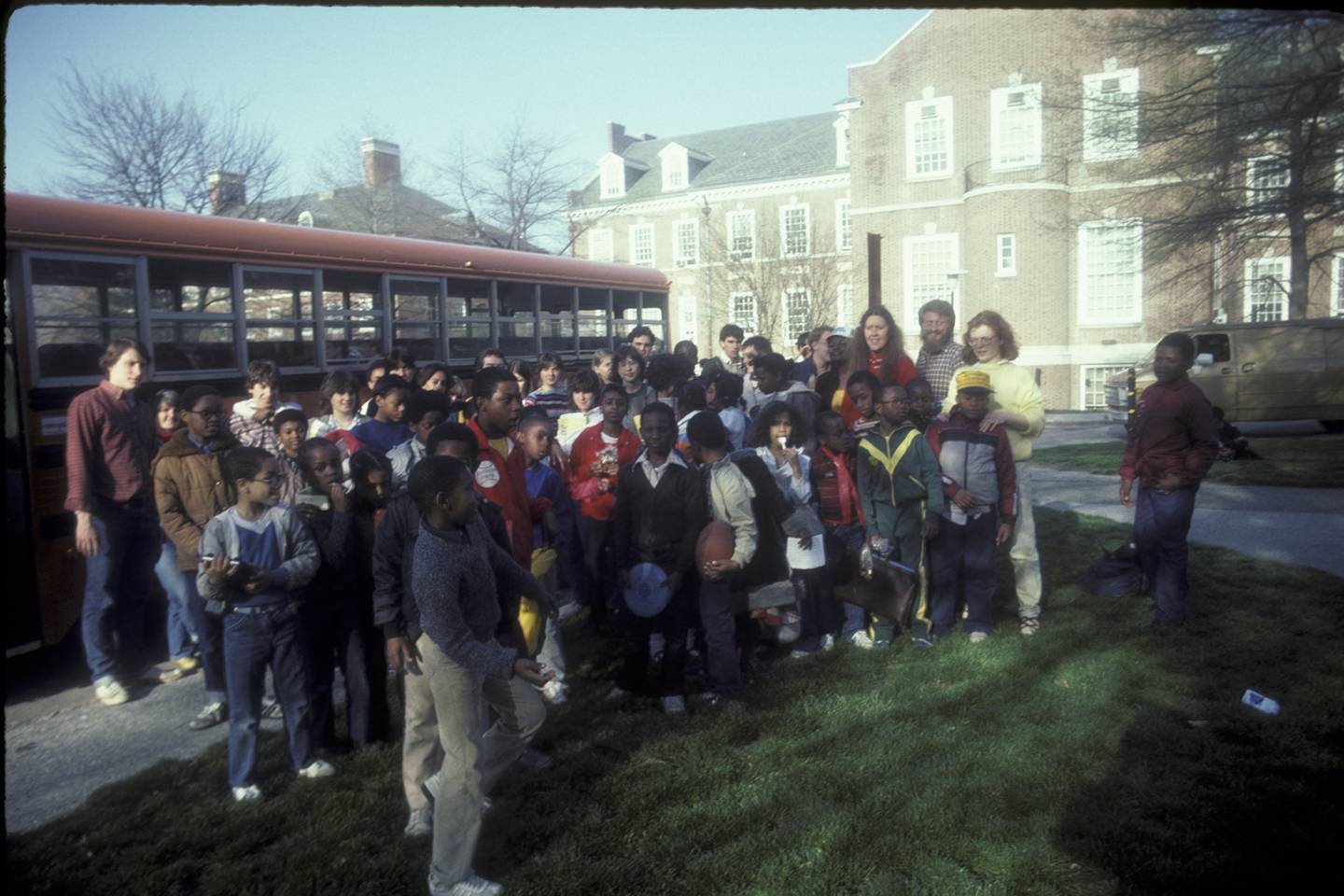

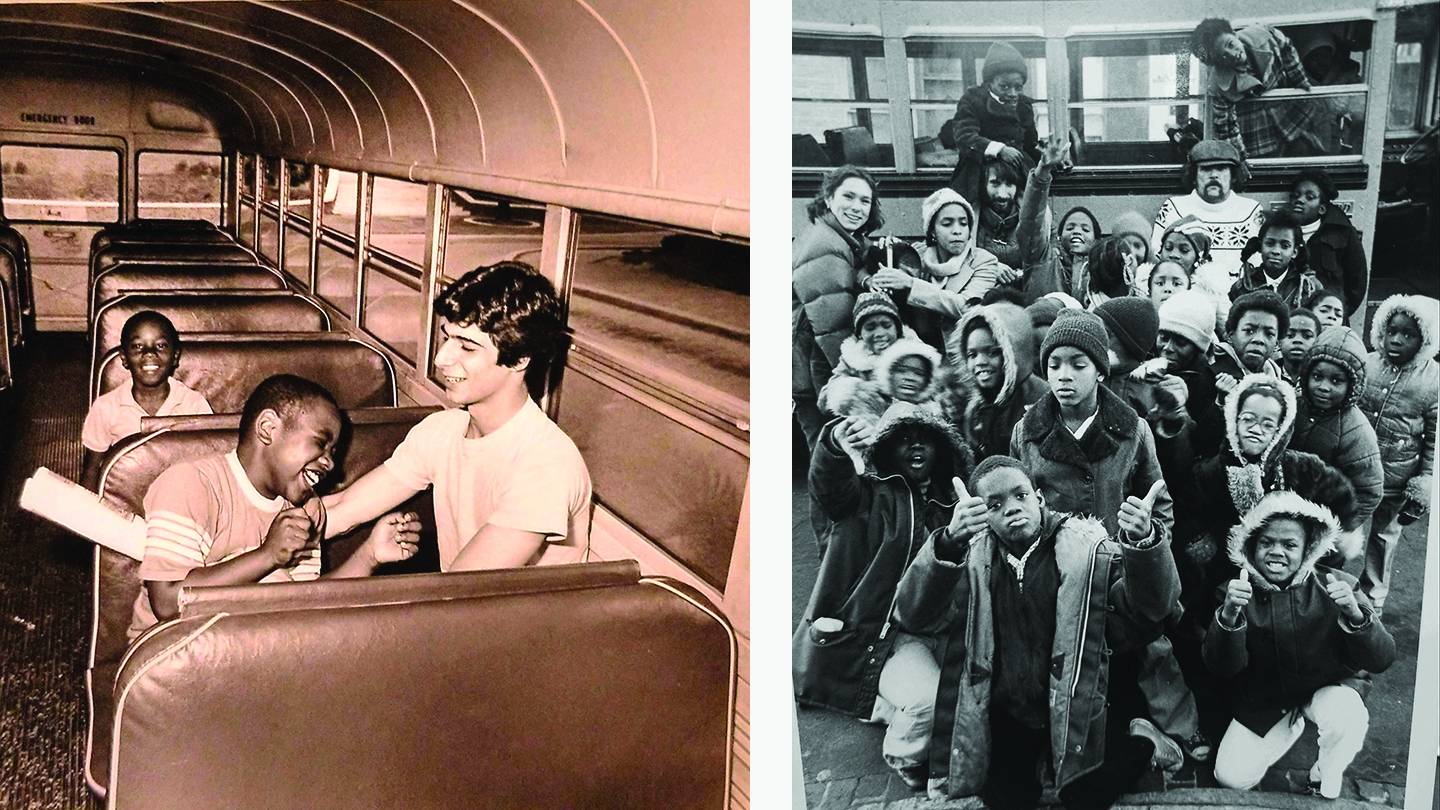

Below are images of moments from the past 60 years of the Johns Hopkins Tutorial Project, provided courtesy of Special Collections at JHU's Sheridan Libraries and the Chester L. Wickwire Papers of the University of Baltimore.

In the program's early days, Hopkins tutors visited students' homes in Baltimore. Originally they worked with high-schoolers, before Wickwire—believing early intervention would make the most difference for at-risk students—shifted the focus to elementary school. Later, amid the civil unrest of the mid-1960s, it was deemed more practical to transport children by bus to the Homewood campus.

Today, buses pick up students from six Baltimore elementary schools, while others arrive on their own by car.

At points in the 1960s, the Tutorial Project could count more than 400 volunteer tutors—not only from Johns Hopkins but also from the University of Baltimore and Goucher College, as well as the now-closed Experimental High School. The project also once included a Saturday program and a summer program.

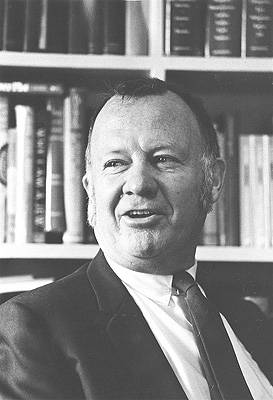

Image caption: Chester Wickwire

Wickwire arrived at Johns Hopkins in 1953 from Yale Divinity School. An anti-segregationist, he organized Baltimore's first integrated concert, recruited talented black high school students to attend the university, and was one of the first members of the Johns Hopkins Club to bring black guests.

In the late '60s, the Baltimore City Council rebuffed a funding request for the Tutorial Project because a group of legislators personally objected to Wickwire and his progressive causes. Council members allegedly called Wickwire "pinko," a disparaging term for individuals believed to be communists or sympathetic to communism.

But by 1980, the program would earn praise from Baltimore's then-mayor, William Donald Schaefer.

"For seventeen years," Schaefer wrote, "you and your predecessors have reached out to our communities and lent a helping hand in the development of hundreds of young minds."

In 1998, Wickwire, then 84 years old, was the guest of honor at the Tutorial Project's 40th anniversary celebration. He told the Johns Hopkins Gazette at the time: "The thing about it I'm most proud of is that getting involved in the tutoring really changed the lives of the people involved. And this is what we tried to do, to relate people in a helping way to the city."

Wickwire died a decade later, the same year his Tutorial Project turned 50.

A group of tutors and tutees gather on the steps outside Levering Hall in 2003. Inside the hall, on the second floor, is the space the Tutorial Project has traditionally called home: a cluster of rooms, including a small library and a row computers. For the actual tutoring sessions, though, most tutors take their tutees to other spots in and around Levering.

"Tutorial is many things," Rachel Austin said of her experience volunteering with the Tutorial Project. "It's peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and apple juice. It's action plans, shaped like watermelons and footballs, checked off with Crayola markers. It's frog games and tens blocks, math problems and money pieces, spelling words and tic-tac-toe. It's the Little Theater, packed full of tutors and tutees, their heads bent together over a worksheet or a set of flashcards. It's playtime, Reverse Session, and Graduation. Most of all, it's hearing a right answer, watching eyes light up, and knowing you made a difference; that every day, our kids are going home with just a little bit more than what they had when they got off the bus."

Posted in University News, Student Life, Politics+Society, Community

Tagged community, student activities, tutorial project