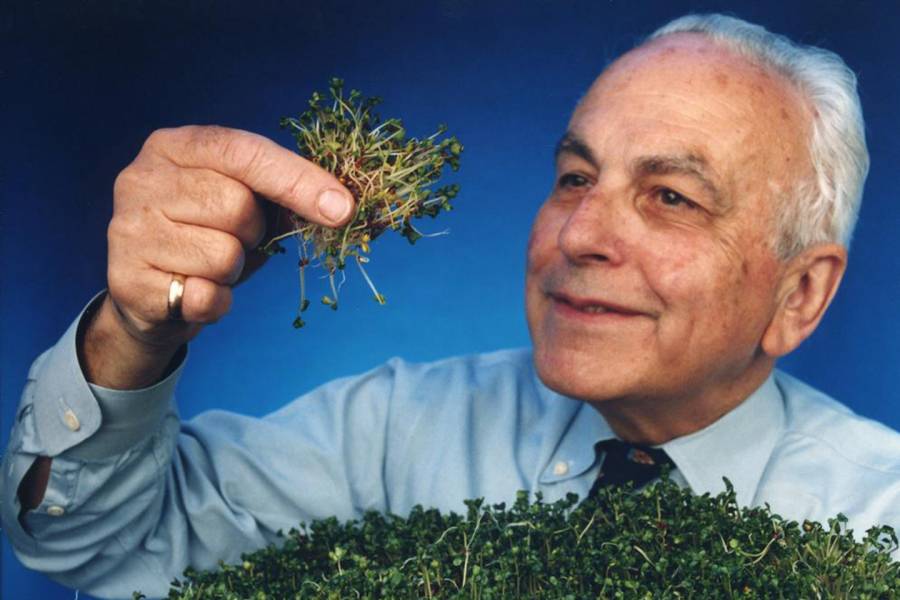

Paul Talalay, an internationally renowned Johns Hopkins pharmacologist whose research on the cancer-prevention properties of a chemical abundant in broccoli sprouts launched the field of "chemoprotection," died March 10. He was 95.

As director of what was then the Johns Hopkins Laboratory for Molecular Pharmacology and is now the Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Chemoprotection Center, Talalay and his research colleagues published a 1992 study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that described a protective biochemical mechanism for the action of sulforaphane, a compound found in broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables.

Glucosinolates—which produce sulforaphane when damaged, as in chewing—are transformed by enzymes present in the plant and in intestinal bacteria into isothiocyanates, which are chemicals that block the development of cancer cells, as later studies from Talalay's group described.

His findings received wide attention in the news media. Although the value of eating plenty of fruits and vegetables was long known, Talalay was so confident about the importance of the chemoprotection concept that he staked his career on it.

Talalay's achievements were far more extensive than his contributions to the field of chemoprotection. He had a careerlong interest in studying enzymes—proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. He developed this interest in medical school at the University of Chicago after receiving his undergraduate degree in molecular biophysics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1944.

At the University of Chicago, he conducted research in the laboratory of surgeon Charles Huggins, who studied how hormone treatment can alter the course of metastatic prostate cancer. The research forever changed the way scientists viewed the development and treatment of cancer—work that earned Huggins the 1966 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Talalay's research extended this work by charting the course of enzymes that break down testosterone in the cell. This led to Talalay's discovery that certain enzymes can protect cells against many types of damage, including cancer development.

Talalay received his medical degree from Yale in 1948, and then returned to Chicago to resume working alongside Huggins. He left Chicago for Baltimore in 1963 when he was recruited to become head of Pharmacology at Johns Hopkins.

He was director of the Johns Hopkins Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics from 1963 to 1975. During that time, he founded the PhD program in pharmacology and fostered creation of the School of Medicine's overall MD/PhD program.

"The passing of Paul Talalay is a tremendous loss to the Johns Hopkins community and the wider world of biomedical research," says Philip A. Cole, former director of the Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences at Johns Hopkins and currently professor of medicine and biological chemistry and molecular pharmacology at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital. "Paul was one of the most impactful scholars in the history of Johns Hopkins and his mentorship, scientific discoveries, and leadership have forever changed the field of medicine."

When Talalay decided in 1993 to switch his laboratory's research from cancer treatment to cancer prevention, many colleagues took a dim view of his new focus. "Cancer was not a preventable disease in their eyes," he said in a 2008 interview with Johns Hopkins Magazine. Funding for cancer-prevention research was scarce, and those interested in it were few.

Since then, the impact of Talalay's pioneering research has been profound. The number of published studies by other researchers in the field each year has jumped from just a handful to hundreds. Talalay's own research has resulted in more findings about sulforaphane's ability to heighten the body's own defenses against cancer. In 2008, he reported development of a topical extract of broccoli that has the potential for protecting skin cells against cancer-promoting damage from the sun.

In 1997, Talalay joined his fellow Johns Hopkins researcher Jed Fahey, a nutritional biochemist, and Talalay's son, Antony, a New York advertising executive, in founding Brassica Protection Products. Originally, the company marketed broccoli sprouts, which contain a higher concentration of sulforaphane than mature broccoli. In 2001, the company launched products featuring what was branded as "TrueBroc," a nutritional ingredient containing high concentrations of glucoraphanin, the precursor of sulforaphane, extracted from broccoli seeds.

"He was quite gratified, though rarely spoke about it, to see how 'his' field had exploded, and to start seeing his theorems, postulates, and hypotheses find their way into textbooks," says Fahey, assistant professor of medicine, pharmacology and molecular sciences and international health, and director of the Cullman Chemoprotection Center. "I was very privileged to bear witness to Paul's happiness over these developments that he was so intimately involved in bringing to the crest of the wave that many, many researchers are now surfing on."

Talalay trained dozens of students in his laboratory and mentored many more in the pharmacology graduate and MD/PhD programs at Johns Hopkins. In 1978, he established the Young Investigators' Day program, which celebrates the outstanding achievements of young investigators who are training at the School of Medicine and provides them with a forum for presentation of their work.

"Paul Talalay was brilliant, charismatic, and wise. It was my great good fortune to train with him, and to have him as a mentor for decades thereafter," says Theresa Shapiro, professor of medicine and pharmacology and molecular sciences at Johns Hopkins and former director of the Division of Clinical Pharmacology. "His advice was always thoughtful, constructive and often quite creative. We have lost a wonderful person and an academic giant."

Talalay received one of the first lifetime professorships of the American Cancer Society. He also was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The youngest of four brothers, Talalay was born in Berlin on March 31, 1923, to Russian parents, Joseph and Sophie Brosterman Talalay. In 1933, his family fled Nazi-controlled Germany for Belgium, France, and finally England.

In 1940, when he was 17, the family boarded a ship that undertook a perilous, 10-day journey through German U-boat infested waters to reach the United States.

Talalay is survived by his wife of 66 years, Pamela; his children Antony, Susan, Rachel, and Sarah; their spouses; and four grandchildren, Sophie, Alex, Lucy and Miriam. He was also devoted to his many nieces and nephews. He resided in Baltimore.

An interment was held March 12 in New Haven, Connecticut. A memorial service at Johns Hopkins is being planned.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged in memoriam