It was the signature white uniform, so crisp and professional, that lured Kereng "Molly" Rammipi into nursing. But decades later and fashion aside, nursing holds even greater appeal for Rammipi and more responsibility than she ever imagined.

She is coordinator of Botswana's National Cervical Cancer Prevention Programme and co-investigator on a groundbreaking human papillomavirus self-collection study conducted in collaboration with global health nonprofit Jhpiego, a Johns Hopkins University affiliate. With authority and evidence on their side, Rammipi and her team of nurses seek to inform and change national policy as it relates to the prevention and treatment of cervical cancer.

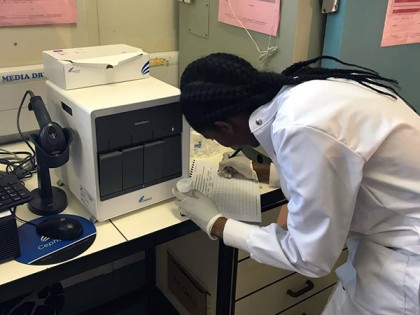

Image caption: Kereng "Molly" Rammipi coordinates Botswana’s National Cervical Cancer Prevention Programme and is a co-investigator on a groundbreaking human papillomavirus self-collection study.

Image credit: Jhpiego

For 20 years, cervical cancer has been a public health priority in Botswana, where it is a leading cause of death for women. Cytology-based screening, commonly called a Pap smear, is generally available at the public primary health care level, but women often don't get timely Pap test results or never get results at all, because in addition to there being too few cytotechnicians and pathologists to review tests, women have to travel to health facilities in order to get their results.

In response to those bottlenecks, the ministry introduced same-day screening and treatment, using visual inspection with acetic acid, coupled with immediate treatment. This single visit approach led to some improvement over the past four years, but challenges remain.

"We are not reaching enough women," Rammipi explained. "We felt that introducing HPV self-collection and testing would go a long way in increasing our still-low screening coverage."

Expanding the reach of cervical cancer prevention called for rigorous study. It called for dedicated and passionate researchers who knew their community and were trusted.

It called for nurses.

"These nurses, they ran the show," said the study's principal investigator, John Varallo, a cervical cancer expert and Jhpiego's global director for safe surgery. "They were it. We put the protocol together, and they ran with it. They did absolutely everything."

At the core of the study, five research nurses enrolled 1,022 participants in the Kweneng East District of Botswana. They recruited and determined eligibility and counseled and instructed women—verbally, in writing, and with pictures—about how to properly collect their own samples, in private, using swabs and vials. The nurses were responsible for making sure the specimens went to a lab to be tested specifically for high-risk HPV types associated with the development of cervical cancer. Finally, they personally contacted each woman to convey results, assisting all who tested HPV-positive to schedule follow-up visual assessments of the cervix and treatment.

"It's cutting edge," Varallo said. "This is the first time Jhpiego is doing HPV testing and doing it through self-collection."

Varallo credited the nurses with "leading Jhpiego's cervical cancer strategy into a new era."

Among the nurses leading the effort is Thebeyame Diswai, who oversaw a study site in Thamaga, situated between three major villages, about 40 kilometers west of Botswana's capital city, Gaborone. Diswai targeted his outreach to malls, workplaces, and community and school events. Wherever he could interact with the women and community leaders, he spoke about the ease of preventing cervical cancer and about the new, private HPV testing method that would deliver accurate results quickly.

Image caption: Research nurse Thebeyame Diswai manages samples and supplies for the HPV self-collection study at the Tamaga Clinic

Image credit: Jhpiego

He explained to the women that HPV testing is more sensitive and reliable in detecting cervical precancer and cancer than other screening methods. He assured them that no matter whether they were from urban areas or remote villages, they could rely on the accuracy of the results.

"People really welcomed the initiative," he said.

Because of the nurses' rapport with community members, the pace of enrollment exceeded all expectations, Varallo said. In fact, not one woman who was offered self-collection for HPV testing declined to participate. In their responses to a survey, 97.2 percent of study participants said the instructions were easy to understand, and 95.1 percent said sample collection was easy. Nearly all participants—97.3 percent—said they experienced minimal to no discomfort and said that they would recommend the HPV self-collection method to others.

"Self-collection has the potential to achieve population-level coverage," Varallo said. "It's been a struggle to scale up our current screen-and-treat approach of VIA coupled with immediate cryotherapy."

Scaling up means reaching more women in more places—and ultimately saving more lives. It's a lofty goal largely dependent on the listening ability of those on the ground at the front lines of care.

Women said they did want to be screened but would prefer an approach that was simple, noninvasive, and private.

Image caption: Key to the effort was the promise of prompt notification and treatment: 75 percent of study participants learned results from a nurse within 3 days, and 85 percent of those who tested HPV-positive completed visual assessment and treatment within three weeks.

Image credit: Jhpiego

"The self-collection method doesn't deter them from going for screening," Rammipi said. "We see it as an advantage that most women would prefer to do the self-collection and then submit the samples."

Added Diswai: "My clients liked doing the collection in private for themselves. That is what was pulling people in: They felt empowered."

Another key was the promise of prompt notification and treatment: 75 percent of study participants learned results from a nurse within three days; 85 percent of the 343 who tested HPV-positive completed visual assessment and treatment within three weeks.

A nurse-led study has other benefits.

"We identified other gaps in care and saw how lifestyle impacts the prevalence of certain conditions," Diswai said. "Research broadens our [nurses'] thinking in terms of innovation."

And there's another advantage, he suggested: When community-dependent research such as the HPV self-collection study is in the capable hands of nurses, it can yield optimal results.

"Nurses are well grounded in working in communities," he said. "They know who to engage and are skilled at how to engage them."

Research opportunities for nurses are not uncommon in Botswana, Rammipi said, attesting to the professional growth of nurses who are passionate and committed to lifelong learning. She credits "a very active nursing council, one that is in the forefront of advocating for nurses to hold leadership positions in this country." Her senior position in the health ministry, for example, requires a broad range of skills spanning training, programming and policy development.

She identifies first as a nurse: "But I'm not wearing the white uniform now."

Posted in Health

Tagged global health, nursing, jhpiego, cervical cancer