Many of Martin Luther King Jr.'s speeches were more powerful than I Have a Dream, his friend Edwina Moss said during a performance and panel talk at Johns Hopkins University on Thursday. The perception of King attached to that speech is a reductive one, she said.

"People want to talk about … he was this soft man, and he was, but behind that softness was a very militant spirit. Dr. King was a radical," said Moss, who worked with the the civil rights leader in 1960s.

"Many people don't see that because they've made him the I Have a Dream person," she added, calling that speech great, but "not his greatest."

In Moss' opinion, the sermon known as The Drum Major Instinct—which was performed Thursday night in the Glass Pavilion on the university's Homewood campus—was among the most powerful speeches the civil rights leader delivered.

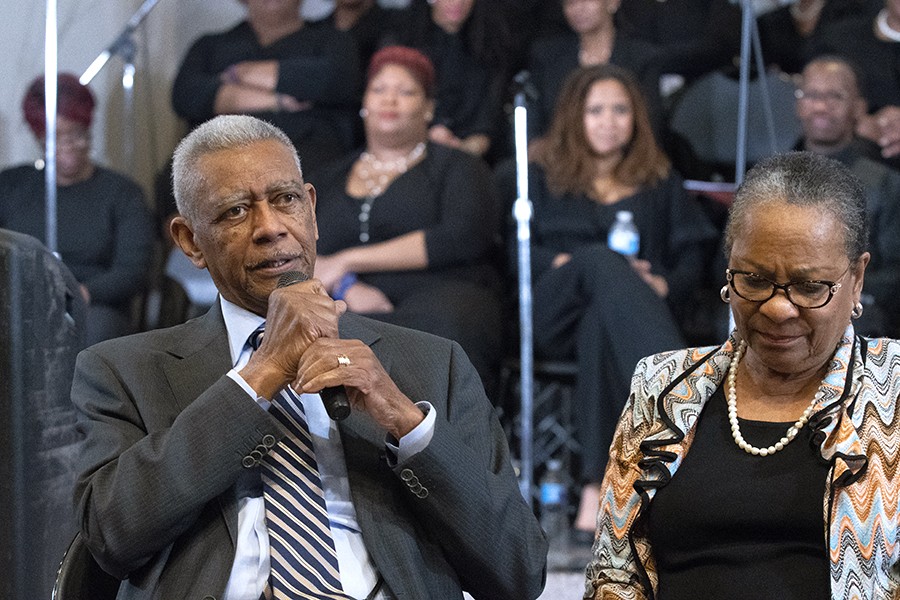

Thursday's performance, part of a touring production named after that 50-year-old speech, featured actress Tracie Thoms, who recited King's sermon backed by a touring choir, the Phil Woodmore Singers, made up of community members of Ferguson, Missouri, where teenager Michael Brown was fatally shot by a police officer in 2014. The production visited Johns Hopkins as part of the JHU Forums on Race in America series and was followed by a panel conversation featuring Moss and her husband, Otis Moss Jr., a prominent theologian and reverend. The Mosses met while both working with King through the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the 1960s, and King himself later officiated the couple's wedding.

King's sermon, delivered from the pulpit of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta on Feb. 4, 1968, reflected on flaws of human ego and vanity—"the drum major instinct," the desire to lead the parade. At their most corrupted, these instincts feed into "the most tragic expressions of man's inhumanity to man," including racism and war, the civil rights leader warned.

Image caption: Actress and Baltimore native Tracie Thoms read the words of Martin Luther King Jr. in The Drum Major Instinct.

Image credit: Karen Jackson

The sermon shows the minister in a more spiritual light than his better-known secular speeches, celebrating the model of Jesus and calling on followers to channel the "drum major instinct" toward justice and peace. In retrospect, the remarks—which King gave just two months before his assassination—can also be seen as chillingly prophetic, ending with the leader's own wishes for posthumous legacy.

During the panel discussion that followed the performance, Otis Moss recalled that Coretta Scott King's sister, upon hearing the original speech, had said: "Coretta, Martin is not going to be with us for much longer."

Moss, who is also an activist, said he has first heard excerpts of The Drum Major Instinct at King's funeral—which also took place at Ebenezer Baptist on April 9, 1968.

Image caption: The performers included the Phil Woodmore Singers and Unified Voices.

Image credit: Karen Jackson

"It's a living message …that is bigger than death, stronger than death," he said Thursday.

The panel discussion also featured Jewell Debnam of Morgan State University and Rabbi Daniel Burg of Baltimore's Beth Am Synagogue, and it included comments from audience members and performers from the choir.

Choir member Duane Foster—a schoolteacher who had taught Brown, whose death sparked a series of protests against police brutality and discrimination—addressed the tension between today's civil rights activists and the message they may hear from their churches and communities to tone down their radicalism.

"Dr. King did not have frosting on his cake," Foster said. "We have got to let these young folks go out without putting frosting on what they're trying to say and what they're trying to do."

The discussion also brought up the topic of white supremacy, both past and present. King addressed that issue indirectly in The Drum Major Instinct, reflecting on his conversations with white wardens of the Birmingham jail—who, despite their own poverty and oppression, "carried the false feeling that [they're] superior" due to the color of their skin.

"Why is white supremacy the same sickness it was then as it was in the year of our Lord 2018?" asked choir member De-Rance Blaylock.

Bryan Doerries—artistic director of Theater of War Productions, which produces The Drum Major Instinct performances—said the "casual nature" of today's white nationalism is most troubling—"the lack of outrage among people who are privileged."

Before the evening's performance, the Black Faculty and Staff Association at Johns Hopkins hosted a luncheon honoring the Mosses, where Edwina reflected on the role of women during King's civil rights era. The association also conducted an interview with Edwina this month (the full transcript is available online) about her relatively unsung role in the movement.

At the evening discussion, Edwina Moss called for overcoming the barriers of anger and fear between people of different races and perspectives.

"Be uncomfortable. It's all right to be uncomfortable," Moss said. "But if we're on this planet, and if we don't open the conversation, we will perish on this planet."

Thursday's event was made possible by the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, the Agora Institute, the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute, the Johns Hopkins Alumni Association, Development and Alumni Relations, the Black Faculty and Staff Association, the Center for Africana Studies, the Diversity Leadership Council, the Black Student Union, Latino Alliance, the Office of Institutional Equity, the Office of Multicultural Affairs, Homewood Student Affairs, the Office of the President, and the Office of the Provost.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society