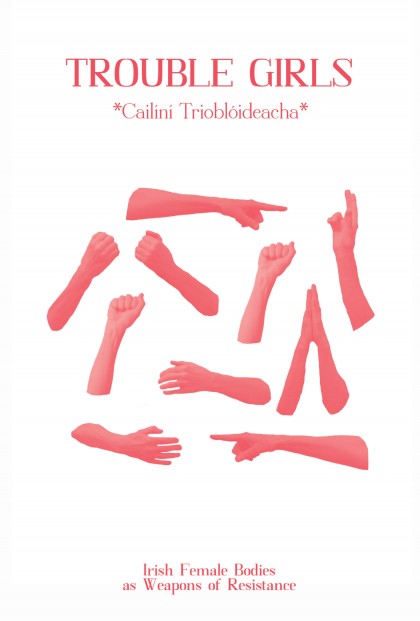

A trio of Baltimore-based activists and artists will speak tonight at the release event for the Trouble Girls zine, the winter research project of Johns Hopkins undergraduate Gillian Waldo.

The zine explores Irish women prisoner protests in the Armagh Gaol during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Poet and Baltimore Transgender Alliance staff writer Jamie Alexander; Brittany Oliver, founding director of Not Without Black Women; and Rosemary Liss, a chef and artist who explores the politics of food will join Waldo for the release tonight at 6 p.m. in Gilman 50.

Waldo, a senior Program in Film and Media Studies major, says she got interested in the Troubles in high school while reading up on the sectarian conflict between mostly Protestant Unionists and loyalists and mostly Catholic Irish Republicans that lasted from the 1960s until the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. The protests waged by jailed Irish republicans in the men's prison the Maze—such as the 1981 hunger strike that resulted in the deaths of Bobby Sands and nine other protesters; and the five-year dirty and blanket protests, in which inmates refused to wear the prison uniforms of common criminals and draped themselves in their cell's blankets instead—not only raised public awareness of their ill treatment but have become the stuff of political resistance legend. The 2008 film Hunger, about the Maze prison and Sands' death, brought both actor Michael Fassbender and director Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave) to Hollywood's attention.

In February 1980, however, Republican women prisoners held in Armagh prison, who numbered more than 100 by the mid 1970s, began their own (albeit lesser-known) dirty protest. When Waldo first came across the Armagh actions, "it got me thinking about how at least in the Irish protest during the Troubles, the emphasis is so much placed on the men as these martyrs in this long history of Irish male martyrdom," she says. "And the women were seen as these mothers who had to sacrifice their sons. The protest in the Armagh Gaol, that's directly transgressing that tradition. The women are using their own bodies on the front lines of political protest in a way that is not as well publicized or documented. Hunger isn't about Mairéad Farrell."

Farrell was one of the Armagh protestors Waldo read about during her research, which, like her Trouble Girls zine, was funded by a winter research grant from the Program for the Study of Women, Gender, and Society. In her zine, she tells the stories of a few women protesters but also provides some context for understanding the history of the sectarian violence in Northern Ireland. She explains who the different factions were, introduces some basic slang terms that may be unfamiliar—prison guards were called "screws," for example—and includes the Five Demands protesting prisoners were fighting for to reassert their status as political detainees.

The Good Friday Accord was signed 20 years ago this month, but two decades of peace haven't completely quelled the political divisions or pushed away the fraught memories of living during sectarian violence. Derry Girls, a sitcom about teenage girls in the 1990s in the titular Northern Ireland city, was a smash hit for Britain's Channel 4 network this winter, praised for its striking balance of nostalgia, dark comedy, and a bleak awareness of life during a guerilla war. Earlier this month, the BBC aired My Dad, the Peace Deal, and Me, a documentary in which comedian and television host Patrick Kielty, whose father was murdered by loyalist paramilitaries in 1988, returns to Northern Ireland to find out what has, and hasn't, changed.

Both programs depict what Waldo is trying to accomplish in Trouble Girls by providing some contextualizing history of the Troubles: spotlighting the everyday, intimate proximity of conflict. It was as partisan as local politics can get and threaded with the same kind of passion one displays while rooting for the home football club.

And the protesting prisoners made dissent personal. The blanket protest evolved into the dirty protest at the Maze when prisoners, refusing to bathe due to their violent treatment from the guards, were confined to solitary and unable to empty their chamber pots. They covered the walls of their cells with their own excrement, bringing attention to the horrid conditions in which they were kept.

Women in the Armagh began their own dirty protest in 1980, responding to the humiliatingly invasive strip searches, which included turning over their sanitary products when they were menstruating. The Armagh women prisoners smeared their menstrual blood on their cell walls.

"The introduction of menstrual blood was so taboo in Irish catholic society that there was no precedent for it," Waldo says. "It transgressed all ideas of Irish femininity. They basically weaponized their bodies. They weaponized what made them vulnerable and different in order to save them from the strip searches and beatings, because the screws were so repulsed by them they wouldn't touch them."

For the Trouble Girls release event, Waldo wanted to open up this idea of women's bodies being the site, focus, and subject of protest and politics to a wider context, and invited the three Baltimore activists to facilitate that discussion.

"I think it's important to bring everybody into this conversation," Waldo says. "I wanted to translate my research into an event that was broader, so I invited three women to speak on the topic of women's bodies writ large."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Student Life, Politics+Society