Researchers studying childhood mortality rates in the United States and 19 economically similar countries over a half century report that while there's been overall improvement among all the countries, the U.S. has been slowest to improve.

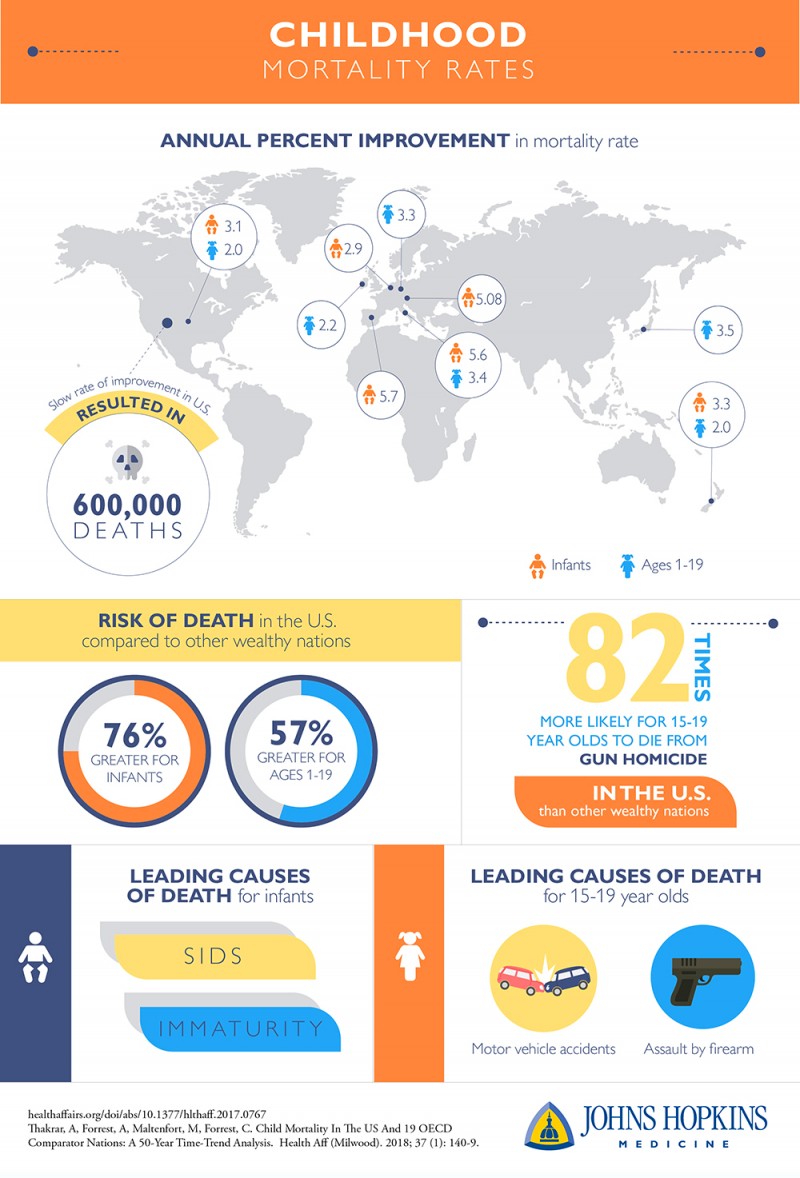

The researchers, who looked at data from 1961 to 2010, found that U.S. childhood mortality has been higher than all other peer nations since the 1980s. Over the 50-year study period, its "lagging improvement" has amounted to more than 600,000 excess deaths.

A report on the findings, published today in Health Affairs, highlights when and why U.S. performance started falling behind that of peer countries and calls for continued funding of federal, state, and local programs that have proven to save children's lives.

Among the leading causes of death for the most recent decade, the researchers say, were premature births and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, or SIDS. Children in the U.S. were three times more likely to die from prematurity at birth and more than twice as likely to die from SIDS.

The two leading causes of death for those 15 to 19 years old in the U.S. during the same period were motor vehicle accidents and assaults by firearm. Teenagers were twice as likely to die from motor vehicle accidents and 82 times more likely to die from gun homicide in the U.S. than in other wealthy nations.

"Overall child mortality in wealthy countries, including the U.S., is improving, but the progress our country has made is considerably slower than progress elsewhere," says Ashish Thakrar, an internal medicine resident at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and a lead author of the study. "Now is not the time to defund the programs that support our children's health."

Thakrar notes that while the U.S. spends more per capita on health care for children than other wealthy nations, it has poorer outcomes than many. In 2013, the United Nations Children's Fund ranked the U.S. 25th of 29 developed countries for overall child health and safety.

To better understand when and why U.S. performance in improving child death rates began faltering compared to peer nations, Thakrar and colleagues tracked child mortality rates for 20 nations that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The members include Canada, Australia, Switzerland, Italy, and Germany, among others, which have similar levels of economic development.

Also see

While previous studies have also tracked U.S. mortality over time, they've only done so for children in specific age groups, Thakrar says, adding that to his knowledge, the new study is the first to describe the full burden of excess mortality in the U.S. for children and adolescents of all ages.

The researchers analyzed mortality and population data from the Human Mortality Database and mortality and cause of death data from the World Health Organization for all children 0 to 19 years old from 1961 to 2010.

Some 90 percent of these deaths, the researchers say, occurred among infants and adolescents 15 to 19 years old. In the most recent decade studied (2001-2010), infants in the U.S. were 76 percent more likely to die and children 1 to 19 years old were 57 percent more likely to die than their counterparts in peer nations.

"The findings show that in terms of protecting child health, we're very far behind where we could be," says Christopher Forrest, the study's senior author and a pediatrician at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. "We hope that policymakers can use these finding to make strategic public health decisions for all U.S. children to ensure that we don't fall further behind peer nations."

The research team called on officials to fully fund the Children's Health Insurance Program, or CHIP, which provides health insurance to millions of disadvantaged children, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, often referred to as food stamps. Applying public health research and solutions to gun violence and car crashes can also help level the playing field for U.S. children, Forrest adds.

Other authors on this paper include Alexandra D. Forrest of the Drexel University College of Medicine and Mitchell Maltenfort of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Posted in Health

Tagged health care, children's health