Today, you almost certainly are not aware, is World Philosophy Day, a day established in 2002 by UNESCO to celebrate "the enduring value of philosophy for the development of human thought."

Here at the Hub, that has us feeling a bit ... well, philosophical. These are complicated times, to be sure—socially, politically, economically, culturally. There are days when it feels as if the world as we know it has been turned on its head.

With that in mind, we wondered what lessons we might derive from some of history's great thinkers, whether their work might offer us a different way of looking at things. For answers and perspective, we turned to Richard Bett, chair of the Department of Philosophy at Johns Hopkins University and an expert on ancient Greek philosophers, with a particular focus on ethics and epistemology.

We asked him: Based on your studies and expertise, how do you make sense of it all? What lights your way? What gives you hope?

This is what he told us.

"The Skeptics of Ancient Greece"

The ancient Greek skeptics found that searching for the truth didn't lead to the intended result; instead of finding anything solid and definite, they found themselves driven to suspension of judgment—there were just too many competing arguments and ideas to try to make sense of.

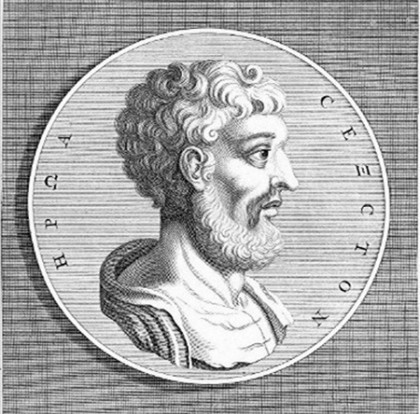

Image caption: Sextus Empiricus

Of course, some people thought they had discovered the truth. But the skeptics' aim was to shake their confidence and get them to suspend judgment, too. They even thought suspension of judgment led to greater peace of mind.

We may disagree about that last bit, at least as a general rule. But the idea of not being too sure of yourself is one that we could definitely use more of today. The writings of Sextus Empiricus, the one ancient Greek skeptic whose works have survived, are full of arguments on opposing sides of an issue, designed to undermine a one-sided commitment to an entrenched position. The issues he deals with are mostly not ones that engage us today. But one valuable lesson we can take from his writings is maybe this: look at all sides of a question whenever possible, and be suspicious of dogmatic claims delivered with bluster rather than evidence.

This may or may not lead to suspension of judgment—maybe in some cases the arguments really are stronger on one side than another—but at least it will give you a more fully examined view of things, and it may also create more of a basis for discussion on common ground with those who may disagree. In a society such as the United States, which is increasingly fragmenting into two parallel societies having different and deeply entrenched values, different media outlets, and different lifestyles in different locations, and where politics and even civil discourse is becoming increasingly dysfunctional as a result, it might be a very good thing if there were more skeptics around.

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged philosophy