There was always a bit of an impractical spirit behind the George Peabody Library, founded as it was amid the turmoil of America's Civil War.

"Building this library of 50,000 books in a decade, in the middle of the Civil War, was kind of crazy," acknowledges curator Earle Havens of the library's starting goal in 1861—when Union troops held Baltimore under martial law.

But the zeal the Peabody founders committed to this mission, Havens suggests, is exactly what distinguishes the public research library as a "unique phenomenon of American intellectual life."

Through some of the library's more curious and memorable acquisitions—50 of which are now on display in a new exhibit—Havens and his fellow curators see a direct link to the craze of "Bibliomania" that took root in England at the turn of the 19th century. The phrase refers to the competitive, sometimes manic, fervor that upper-class bibliophiles applied toward hunting down rare books for prolific collections that sometimes rivaled those of kings or princes.

Also see

The trend had crossed over the Atlantic right around the time the George Peabody Library first opened in Baltimore, in 1866. From its start, the library in Mount Vernon sought to balance its civic mission as a public repository of great books with this more lavish pursuit of rare and curious treasures.

For the new exhibition, Bibliomania: 150 Years of Collecting Rare Books at the George Peabody Library, curators plumbed the depths of the collection to find memorable artifacts and manuscripts dating back as early as the 14th century.

Two doctoral students at Johns Hopkins worked with Havens, who curates rare books for JHU's Sheridan Libraries, to organize the exhibit and produce an accompanying book. (The Peabody Library formally merged with the Sheridan Libraries in 1986.)

Below, the three curators point to their personal favorites from the exhibit, which runs through Jan. 31 at the library's home at 17 East Mount Vernon Place:

Earle Havens, Nancy H. Hall Curator of Rare Books & Manuscripts

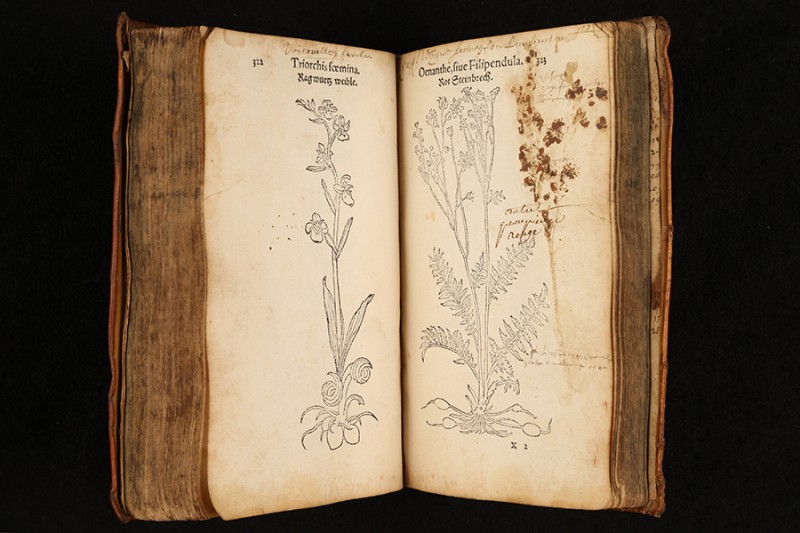

We have at Peabody a small, portable copy of Leonhart Fuchs' De stirpium(1545), a popular illustrated Renaissance herbal filled with printed texts and early manuscript margins describing the physical characteristics and medicinal applications of plants. One opening in the book reveals the silhouette of an actual botanical specimen gathered centuries ago—a common water dropwort (oenanthe) identified in a printed woodcut on the same page. It happens that a species of dropwort (oenanthe javanica) is a native vegetable in Asia.

Image caption: This small, portable copy of Leonhart Fuchs' De stirpium(1545) is filled with printed texts and early manuscript margins describing the physical characteristics and medicinal applications of plants. Pictured is a silhouette of a common water dropwort (oenanthe)

Image credit: George Peabody Library

This plant was not identified in the mid-Atlantic states until 2008, and since has been popular among Asian immigrants in the region for planting along the edges of springs and streams, and actively cultivating it as an edible green. We corresponded with its discoverer, Rod Simmons, who supplied us with an actual living version of the mid-Atlantic plant—which is displayed alongside the book and the much earlier plant outline in the exhibition. Fuchs' name, and renown, as a great German botanist has given us the name of the color "fuchsia" in English today, and in honor of him, we printed the exhibition label in that color.

Chris Geekie, recent PhD in Italian Studies, Department of German and Romance Languages and Literatures

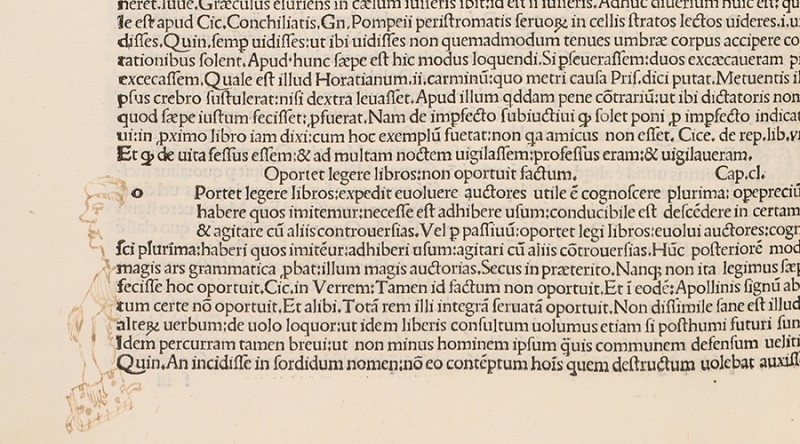

My favorite item is probably the doodle of a man holding a book found in the margins of a 1496 copy of Lorenzo Valla's Elegantiae linguae Latinae. I stumbled across this doodle while working on my article for the catalogue, where I discuss the first modern public research libraries in 15th-century Italy. While looking through our collection of "incunables"—books printed before 1501—I discovered that we had a copy of Valla's Elegantiae, a humanist treatise that sets forward standards for writing well in Latin. I started flipping through the volume and almost immediately spotted the doodle.

Image caption: This doodle was found in the margins of a 1496 copy of Lorenzo Valla's Elegantiae linguae Latinae

Image credit: George Peabody Library

Judging by the quality of the ink, the figure is nearly contemporary to the printing of the book. What's more, he's emerging from a paragraph on stylistic exercises where all the examples concern book-reading. Left perhaps by some daydreaming student?

Neil Weijer, postdoctoral curatorial fellow in Premodern and Early Modern Studies, Sheridan Libraries

One of the marvels of the Peabody collection is a "prayer book" that was commissioned by a merchant, Hans Luneborch, from the northern German city of Lübeck near the end of the 15th century. Despite the book's small size (just over 4 inches tall and 3 wide), its illustrated scenes from the life of Christ and the saints are incredibly detailed, as are its vibrantly colored borders filled with flora and fauna. The book even depicts Luneborch himself as the donor kneeling in prayer in front of the manuscripts.

Image caption: This "prayer book" was commissioned near the end of the 15th century by Hans Luneborch, a merchant from the northern German city of Lübeck

Image credit: George Peabody Library

Books such as these were prized possessions during and after the Middle Ages, and the Peabody trustee who donated the manuscript to the library in 1909, Michael Jenkins, must have intended it to be one of the Peabody's treasures. The book's travels did not end there, however: It subsequently disappeared from the library in the middle of the 20th century for at least 50 years before being mailed back anonymously in 2007. After its return, the manuscript was taken out of its binding to be conserved and digitized, and as a result we are able to display, for the first and only time, four breathtaking illuminations together in this exhibition.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged exhibits, sheridan libraries, george peabody library, peabody archives