Editor's note: This feature was originally published by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs.

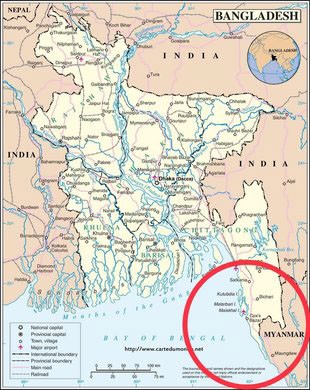

For nearly two months, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have streamed into Bangladeshi refugee camps from neighboring Myanmar, where members of this Muslim minority are being forced from their homes.

A few weeks ago, a team of three Bangladesh-based staff from the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs visited one of the 12 refugee camps set up along the border to see a public health crisis in the making. They found tents and tin shacks set up in former rice paddies teeming with people who need food, clothing, and shelter. They also need basic health needs met.

Also see

Since 1987, CCP has worked in Bangladesh to help its people adopt healthy behaviors. The United States Agency for International Development, Ministry of Health, UNICEF, and other UN agencies have called on CCP during this burgeoning humanitarian crisis to assist with the emergency response. CCP will help develop appropriate health messages to train the front-line workers, community mobilizers, and counselors that the government and NGOs are deploying.

In a crisis, getting important health information to people can be nearly as important as food and clean drinking water.

Image credit: Tania Jahan

No one really knows how many Rohingya have streamed into Bangladeshi refugee camps since the end of August from neighboring Myanmar. Roughly 800,000 are believed to have arrived in recent weeks, joining an estimated 500,000 who have come in waves since 1991.

Image credit: Tania Jahan

Thousands come every day to Cox's Bazar, a fishing and farming area previously known for its miles of unbroken beaches. It is now a temporary home for this long-persecuted minority group, which the United Nations has called the "most friendless people in the world."

The Rohingya have been fleeing Myanmar's western Rakhine State since Aug. 25, when a militant Rohingya group attacked a series of military outposts, prompting a brutal crackdown by the Myanmar military in retaliation.

Where tree-lined hills and rice paddies have long stood in this slice of eastern Bangladesh, now, as far as the eye can see, it is tents, tin shacks, and lines of people waiting for food, water, and other basic needs.

The refugees are currently in overcrowded makeshift settlements that lack clean water and sanitation. Coupled with poor health and hygiene practices, the situation appears to be a public health crisis in the making. Given this state of emergency, CCP and other organizations are trying to get necessary health information to the refugees through community mobilizers, radio programs, and other means.

Image credit: Tania Jahan

Late last month, a team of three CCP staff working on Project Ujjiban, a five-year, USAID-funded social and behavior change communication initiative, visited one of the 12 camps set up along the border. Tania Jahan took these photos to document what she and the others saw. Three weeks earlier, some Rohingya were being shot at as they attempted to enter Bangladesh. Children already on-site were drinking out of mud puddles. On this visit, while some basic needs were being met, it was obvious that tougher times are coming.

"You get a tent, a blanket, that's about it," says Patrick Coleman, chief of party and senior technical advisor for CCP in Bangladesh. "You line up every day for food. You line up for water. There's very little electricity, and information is hard to come by."

Image credit: Tania Jahan

The roads are just mud, the rains have kept coming, and supplies have trouble getting in. Many refugees have arrived by boat, and some have lost their lives in the process. Others have walked for more than 10 days to cross the border over the mountains. They arrive emaciated with only the clothes on their backs. Officials expect that diseases will begin to spread. Cholera vaccination campaigns have begun.

Image credit: Tania Jahan

Many of the children have never received any vaccinations before, as the Rohingya were not given access to the medical system in Myanmar. Women have been giving birth in unsanitary conditions and they refuse family planning methods, which they perceive as a plot to keep their numbers down. That means every day more women become pregnant, and malnutrition and infant mortality risks rise.

There is also a risk of violence since there is nothing to do in the camps but to wait in line for relief handouts. Tempers grow increasingly short, and people have very little to do to take their minds off the dire situation.

Image credit: Tania Jahan

"The situation has spiraled into the world's fastest-developing refugee emergency and a humanitarian and human rights nightmare," United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres told a Security Council meeting on the situation in Myanmar a few days before the CCP visit.

The Secretary-General has called for "swift action" to prevent further instability and find a sustainable solution.

Many of the Rohingya people have a misconception that immunizations cause sterilization or impotence. Many don't understand that disease can be spread by dirty hands or drinking dirty water. Appropriate health messages need to be designed to train the front-line workers, community mobilizers, and counselors that the government and NGOs are deploying to help.

Image credit: Tania Jahan

It's all happening so fast. While aid workers are trying to better understand what the Rohingya already know about good health-seeking behavior, CCP is developing a training curriculum for community mobilizers and messages to help refugees understand hygiene, family planning, and infant survival. There are language and literacy barriers. Those who are charged with educating the refugees will need to speak Rohingya, and they will need materials that use pictures more than words in order to be understood by refugees with low literacy rates.

CCP has also been in talks with local radio stations about creating programs that contain health messages. The center has spoken with mobile phone carriers to create charging stations in the camps and a call-in line so people who do have phones can get health information.

Image credit: Tania Jahan

Efforts are also under way to help map out the camp and all the facilities, so that people will know where to go for medical, social, and psychological assistance or security needs. There are makeshift child care centers being set up, so children have a safe place to go while their parents wait in endless lines for food and water.

"We were already working in this area of Bangladesh, and so we are partnering with UNICEF and USAID to figure out how to leverage our experience and expertise to help here," says Sanjanthi Velu, a senior program officer for CCP. "We are there at the right time to be able to help with this emergency response."

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged public health, global health, myanmar, refugee crisis, center for communication programs