A version of this article originally appeared on Global Health NOW, a forum for news and information for the global health community produced by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

For obvious and rightful reasons, most of the resources and attention galvanized by the Zika outbreak in Brazil have focused on the thousands of children born with microcephaly and congenital Zika syndrome, or CZS. But in already marginalized environments, the entire family ecosystem is changed by the birth of a child with a condition as complex and demanding as CZS. For many impacted families, the child with CZS was not their first—nor their last—born. This photo series centers on the other children: the siblings who also feel and carry the weight of the Zika epidemic.

Image credit: Poonam Daryani

Dhulha Alen Silva do Nascimento, 25, has become skilled at reading and interpreting neuroimages since her youngest daughter, Valentina, was born nearly two years ago with congenital Zika syndrome. She explains a CT scan of Valentina's brain, pointing out areas of calcification and hydrocephalus, while her 4-year-old son, affectionately called Jorge, plays phone games on the couch with his baby sister laying beside him.

Also see

Dhulha has a third child, an 8-year-old daughter named Tarcyla Vitória do Nascimento, who has been living with her grandmother since Valentina was four months old. Dhulha said it was "too much to handle all three children," given Valentina's needs, and that her ex-husband's mother finds fulfillment and joy in raising Tarcyla. Her daughter comes to visit on some weekends and holidays.

Image credit: Poonam Daryani

Jorge, 4, scrambles onto the couch to curl up next to his sister, Valentina. He follows her around, oozing with big-brother love and showering her with snuggles, kisses, and hugs. His adoration is heartwarming in its sincerity. Though caring for Valentina takes up much of Dhulha's energy and time, she says that "Jorge is crazy about his sister, not jealous."

Image credit: Poonam Daryani

On a lazy Saturday morning at home, Jorge watches cartoons and eats marshmallows with his stepfather, Luiz Carlos Ribeiro Valadares Jr., while Valentina naps on a mattress near him, and Dhulha cooks lunch for the family. Inspired by the cartoons, Jorge, who would rather be known as "Spiderman," races around the house, shooting imaginary webs from his wrists. A neighbor from the community has stopped by with her 10-year-old son, who was born with microcephaly due to causes unrelated to Zika. In Dhulha's municipality alone, there are 40 families with children with congenital Zika syndrome, and another 25 with children with microcephaly not associated with Zika.

Image credit: Poonam Daryani

Jorge takes a pause from playing with his cousins to hug Valentina, as Dhulha's niece softly pleas with an aunt to let her hold Valentina in her lap. Dhulha's extended, multi-generational family lives down the street from her and regularly spends time with Jorge and Valentina. Her family has been in this community for the past 25 years; the neighbors wave and smile as they walk past. "Even the drug dealers here look out for us," Dhulha says. "Everyone asks about Valentina. They will check with us before they play loud music or do fireworks to make sure they are not disturbing her."

Image credit: Poonam Daryani

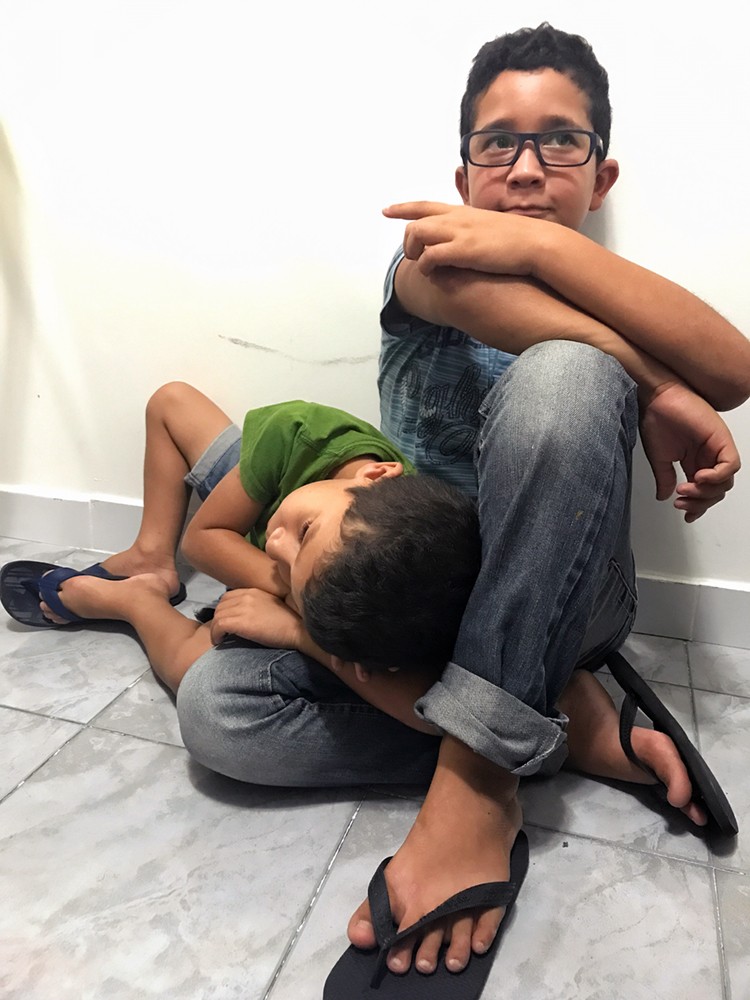

Mylene Helena dos Santos Ferreira, 23, opens a package of chocolate biscuits for her eager sons while balancing her son Davi in her lap. Davi Herrique Ferreira da Silva was born in August 2015 with congenital Zika syndrome. Shirtless on the twin bed is Mylene's oldest son, 5-year-old Richard Miguel; next to him in the green outfit is Angelo Rafael, age 4. When Davi was only a few months old, Mylene left her abusive husband of eight years. He now refuses to acknowledge Davi, but when Davi falls sick, Mylene must send her older sons to stay with him. In July, Mylene was at the hospital with Davi for nearly two weeks while he was treated for a severe respiratory infection. Miguel and Rafael did not see her during this time. "Whenever I talked to them on the phone, they asked when I was coming home," Mylene said. These photographs were taken the week she and Davi returned from the hospital.

Image credit: Poonam Daryani

Rafael peers curiously at Davi, while Miguel gently touches his face. The boys are tireless and rowdy; the house rings with sounds of their play and mischief. With Davi, however, they are calmer—softer. "They are afraid of hurting him, but they are always giving him kisses," says Mylene.

Image credit: Poonam Daryani

Only limbs are visible as Miguel and Rafael wrestle on the floor, growls and yelps and laughter rising from the tussle. Davi glances over, unperturbed by their ruckus. Although she's always shouting—futilely—for Miguel and Rafael to calm down, Mylene says that "when they are not here, the house feels hollow. It's too quiet ... I worry about not being able to provide food and a house for them." For his upcoming birthday celebration, Miguel wants to cut an Avengers cake at home. Mylene says she is not sure if she can afford a themed cake, or if she will have the time to bake and decorate one herself.

Image credit: Poonam Daryani

Josimary Gomes da Silva, 36, waits with three of her children for her son's physical therapy appointment at a specialized microcephaly and congenital Zika syndrome clinic in Campina Grande, Paraíba. Her youngest son, Gilberto, was born with congenital Zika syndrome in 2015. With her at the IPESQ clinic are Marcos, 10, and Jorge, 6; her two oldest sons are teenagers and stayed home. "My ex-husband did not want to see Gilberto's face, so I threw him out," Josimary tells me. A single mom, she makes the two-and-half-hour journey from her home to clinics and rehab centers in Campina Grande four times a week. Once a week, when Gilberto has a full day of appointments, Marcos and Jorge have to miss school to come with her into the city. This morning, they left home at 5:40 a.m. and will return after the sun sets.

Image credit: Poonam Daryani

Jorge lies on his older brother's lap while they wait for Gilberto to finish his physical therapy appointment at the IPESQ clinic. Adriana Melo, an obstetrician who rose to national prominence in 2015 after being the first person to isolate the Zika virus in the amniotic fluid of pregnant patients, says that last week, when Jorge came with his mother to the clinic, "he said to me, 'Doctor, I have microcephaly!' He asked if he could have the same milk and medications as Gilberto. He wants to feel special, too."

Image credit: Poonam Daryani

Marcos holds Gilberto and chats with others at the IPESQ clinic while waiting for his mother. "I feel like her helper," he says. "If I wasn't in my mother's life, how would she do this all right now? I help a lot with Gilberto." Marcos fantasizes about traveling to China. When asked why, he says, "because it's on the other side of the world from Brazil."

About the author

Poonam Daryani received her MPH from Johns Hopkins University in May 2017 and is currently a Clinical Fellow with the Yale Global Health Justice Partnership. Her reporting for this story was supported by the Johns Hopkins-Pulitzer Center Global Health Reporting Fellowship. Interpretation was provided by Rafael Alkalai, Tiago Cabral, Adriana Bentes dos Santos, and Margarida Corrêa Neto.

Read more of Daryani's reporting on the impact of the Zika outbreak on women's sexual and reproductive health, and subscribe to the Global Health NOW weekday newsletter.

Posted in Health

Tagged global health, maternal health, zika virus