Baltimore City Public Schools, in collaboration with Johns Hopkins University, has adopted a program to strengthen science, technology, engineering, and math instruction in the district's elementary schools.

The partnership marks a significant milestone for the program—STEM Achievement in Baltimore Elementary Schools, or SABES—which was designed to prepare students for recently introduced Next Generation Science Standards and bolster teachers' command of the subject matter.

With a $7.4 million grant from the National Science Foundation, SABES was introduced in 2013 as a pilot program in nine elementary schools to bring more instruction in STEM disciplines.

"The fact that the district has recognized the success of our SABES schools and invested in rolling this out across the city is a step forward for our children's futures," said Michael Falk, professor of materials science and engineering at JHU's Whiting School of Engineering and the principal investigator for the SABES project. "Getting kids to work hands-on with science and engineering is essential for instilling the wonder with our world that helps kindle a lifelong pursuit of careers in these directions."

Janise Lane, Baltimore City Public Schools' executive director of teaching and learning, said that under SABES, students tackle scientific topics in three stages. They read about the scientific concept, try to model the phenomenon using real materials, then work on solving a problem related to the idea.

Christine Newman, the Whiting School's assistant dean for engineering educational outreach and head of the Johns Hopkins Center for Educational Outreach, said the city school system's decision to use the SABES program is "an opportunity for Baltimore City to lead the state in Next Generation elementary science standards." These new standards for K-12 science instruction—emphasizing student-driven inquiry and a focus on concepts that apply across scientific disciplines—were first adopted by the state of Maryland in 2013.

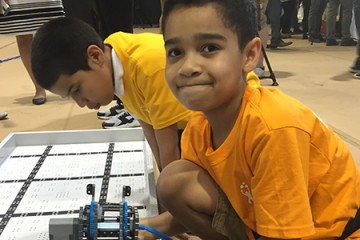

Under the SABES program, schools provide 45 minutes a day of classroom science instruction for students in grades 3 through 5. SABES, which currently involves about 2,200 students and more than 200 teachers, has enabled youngsters to study in class, devise after-school projects, and present their work at two annual showcases.

The city school district plans to expand the program to all 124 schools that have elementary grades, including 25 charter schools, although the charter schools will have more flexibility on whether they adopt the SABES program. Along with instruction for students, SABES also includes professional development courses for teachers who want to bolster their command of science and their skill in teaching it.

Research on SABES suggests that the effort is boosting student interest in science and engineering. A survey administered by the Johns Hopkins School of Education showed that at the end of the 2014-2015 school year, the number of students in SABES who wanted to be an engineer was 27 percent higher than in non-SABES schools.

Lane said that 65 percent of the city's traditional elementary schools received science materials for some grades, with the goal of introducing SABES to all students in kindergarten through 5th grade. The school district is applying for grants for the approximately $2.4 million needed to provide SABES to all elementary students.

Posted in Science+Technology, University News

Tagged stem education, stem, sabes, baltimore city, baltimore city public schools