Jed Fahey is a nutritional biochemist and assistant professor of medicine and director of the Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Chemoprotection Center at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. This op-ed originally appeared in the 2017 Spring/Summer issue of the Johns Hopkins Health Review.

We are obsessed with so-called superfoods, drawn to the promise of berries, roots, leaves, or seeds that can singlehandedly prevent disease, help us lose weight, improve muscle and skin tone, enhance our sex life, and even help us live longer. But do they really live up to the hype?

Image caption: Jed Fahey

Image credit: Marshall Clarke

The term "superfood" isn't new; in fact, it first showed up around 1915 as a well-intentioned aphorism used in scientific papers to describe the bountiful nutritional and pharmacological benefits of infant formula, soy and other legumes, and microalgae. It began to make its way into the popular consciousness in the early 2000s, when the food industry adopted it as a marketing term to promote the latest exotic plant, fruit, or vegetable you needed to include in your diet for various health benefits. Nutritional biochemists like me tease apart these foods and attempt to see whether they live up to their lofty promises. So far we've found that, in isolation at least, most of them don't. It's unreasonable to expect a single food to bestow such comprehensive benefits.

That's not to say, of course, that eating them along with other healthy foods won't improve your health. In fact, science continues to uncover evidence that a healthy diet combined with exercise can increase what we call the healthspan—the period in which we are in generally good health, free of chronic disease and debilitating symptoms. So before you fill your plate with exotic and expensive foods like goji berries, acai berries, chia seeds, or quinoa, check out the nutritious, delicious, and relatively inexpensive fresh foods—like kale, tomatoes, blueberries, fish, and meats—that are often produced locally and sustainably. We citizens of the most privileged nation on earth have at our fingertips foods packed with beneficial phytochemicals (compounds that are present in edible plants at very low levels but are not required to sustain life), high in protein, and loaded with polyunsaturated fats that, eaten in combination, give us the vitamins and minerals we need.

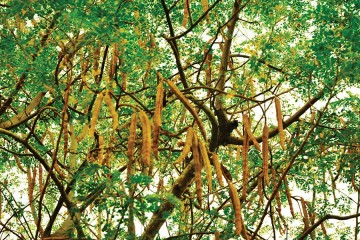

It's also worth noting that superfoods can come at a price—and not just at the checkout. Many of these fad foods originate in developing countries, and producing them for mass consumption can have unintended consequences for the farmers and communities involved in that production. Take the latest superfood, Moringa oleifera. Moringa is a fast-growing tree with edible, highly nutritious leaves that are unusually rich in protein and a variety of vitamins and minerals. The tree thrives in many tropical regions of the globe where poverty and malnutrition are endemic. There's growing peer-reviewed biomedical evidence—and there are even a few small clinical trials—to back up moringa's phytopharmaceutical potential, meaning its anti-inflammatory, cardio-protective, anti-asthmatic, antibiotic, and anti-diabetic properties.

Many of those in the international nutrition community are familiar with the stories of the moringa's first flush of popularity in the 1970s and 1980s. Speculators, perhaps well-meaning, contracted with subsistence farmers in places like Bangladesh where the tree grows. The farmers gave up traditional crops that were needed to feed their families and instead planted moringa, lured by the promise of American dollars. By the time the harvest was ready, demand in the West had already waned, and the speculators never came back. Many farmers were left out in the cold economically, putting their families in tremendous hardship. Now that moringa is making a comeback, these get-rich-quick schemes continue. A recent Nigeria Today article titled "Farmers can make millions from moringa farming" cites a 50 percent annual increase in the price of moringa seeds over the past few years and encourages Nigerian farmers to jump on the bandwagon. What happens if the fad fades again?

Another example is the Andean grain quinoa. Once a regional staple, it caught the attention of American consumers, and demand drove up the price higher than the locals could afford. So now, while we dine on high-protein quinoa, Andeans go without. The good news is that there are growing numbers of responsible and ethical producers of moringa, quinoa, and other superfoods, but this sort of scenario threatens to play out over and over again.

My advice is to think twice before you succumb to the next cure-du-jour and run out to buy this week's superfood. It might cure what ails you (though probably not). Better to take a thorough look at your lifestyle, habits, and diet. Choose from the widely available healthy foods and go for a long walk!

Posted in Health

Tagged nutrition, superfoods