Researchers from Johns Hopkins Medicine and their collaborators say that low levels of a specific protein in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease may contribute to changes in the pattern of neural activity that ultimately lead to the learning and memory loss that are hallmarks of the disease.

The Hopkins scientists—together with colleagues at the National Institutes of Health, the University of California San Diego Shiley-Marcos Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, Columbia University, and the Institute for Basic Research in Staten Island—studied human brain tissue samples and genetically engineered mice. They say their discovery could one day help experts develop new and better therapies for Alzheimer's and other forms of cognitive decline.

Their study is described online in the April 25 edition of eLife.

Alzheimer's disease currently affects more than 5 million Americans, and there is no known cure, though symptoms can be sometimes be slowed or temporarily managed with medications or other treatment approaches.

Clumps of proteins called amyloid plaques, long seen in the brains of people with Alzheimer's, are often blamed for the mental decline associated with the disease. But autopsies and brain imaging studies reveal that people can have high levels of amyloid without displaying symptoms of the disease, calling into question whether there is a direct link between amyloid and dementia.

This new study shows that when the protein NPTX2 is "turned down" at the same time that amyloid is accumulating in the brain, circuit adaptations that are essential for neurons to "speak in unison" are disrupted, resulting in a failure of memory.

"These findings represent something extraordinarily interesting about how cognition fails in human Alzheimer's disease," says Paul Worley, a neuroscientist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the paper's senior author. "The key point here is that it's the combination of amyloid and low NPTX2 that leads to cognitive failure."

Since the 1990s, Worley's group has been studying a set of genes known as "immediate early genes," so called because they're activated almost instantly in brain cells when people and other animals have an experience that results in a new memory.

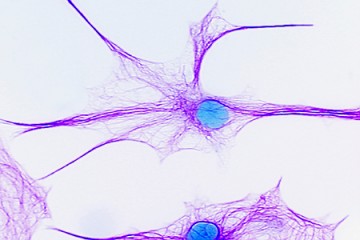

The gene NPTX2 is one of these immediate early genes that gets activated and makes a protein that neurons use to strengthen "circuits" in the brain.

"Those connections are essential for the brain to establish synchronized groups of 'circuits' in response to experiences," Worley says. "Without them, neuronal activation cannot be effectively synchronized and the brain cannot process information."

Read more from Hopkins MedicinePosted in Health

Tagged neuroscience, alzheimer's disease