Certain strategies currently being studied for treating and curing HIV could lead to harmful brain inflammation, a new study from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine has found.

Part of the difficulty of curing HIV is that the virus is capable of remaining dormant in cells for long periods of time. Common therapies include antiretroviral medications that keep the virus controlled without eradicating it. As a result, HIV is treated as a chronic condition.

But new avenues of research are being explored that involve using so-called latency-reversing agents to awaken the dormant virus with the goal of combining the patient's immune system and antiretroviral medicines to eliminate HIV in the body.

New evidence based on a study of macaques infected with HIV's close cousin, simian immunodeficiency virus, indicates that such strategies—called "shock and kill"—could cause potentially harmful brain inflammation. A report on the findings is published online in the Jan. 2 issue of the journal AIDS.

"The potential for the brain to harbor significant HIV reservoirs that could pose a danger if activated hasn't received much attention in the HIV eradication field," says Janice Clements, a professor of molecular and comparative pathobiology at JHU's School of Medicine. "Our study sounds a major cautionary note about the potential for unintended consequences of the shock-and-kill treatment strategy."

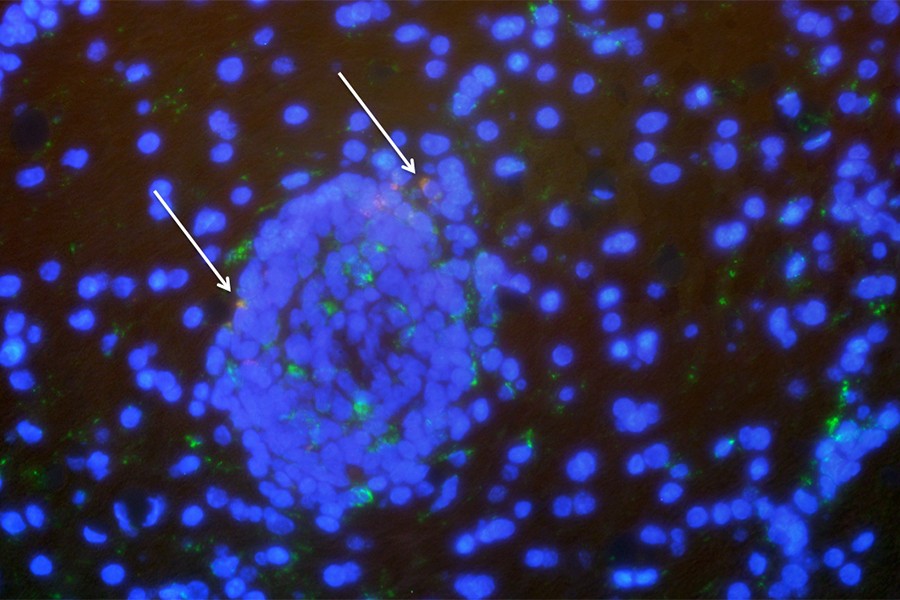

Clements and her collaborators—including lead author Lucio Gama, an assistant professor of molecular and comparative pathobiology—studied three SIV-infected pig-tailed macaque monkeys. The monkeys were treated with antiretrovirals for more than a year before researchers added latency-reversing agents, ingenol-B and vorinostat, to the treatment regimen of two of the monkeys in order to "wake up" the dormant virus.

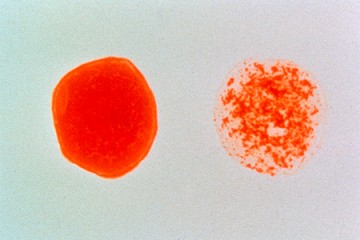

Of the two monkeys receiving the combined treatment, one remained healthy while the other developed symptoms of brain inflammation after 10 days. Blood tests also revealed an active SIV infection. During an autopsy of the animal's brain, researchers discovered SIV in the occipital cortex, which processes visual information.

The researchers say that the results might not apply to human patients with HIV, and that it's possible that the inflammation could have resolved itself. However, Gama says, the results signal a need for extra caution in exploring ways to flush out reservoirs of dormant HIV and eradicate the virus from the body.

Read more from Hopkins Medicine