What if human beings didn't taste so good to mosquitoes? A new study from Johns Hopkins Medicine focuses on that possibility as a pathway for reducing malaria rates.

The researchers discovered that a specialized area of the mosquito brain mixes tastes with smells to create unique and preferred flavors. The findings, published this month in Nature Communications, advance the potential of identifying a substance to make "human flavor" repulsive to malaria-bearing mosquitoes so that they keep the disease to themselves, potentially saving an estimated 450,000 lives a year worldwide.

Malaria, an infectious disease transmitted by the bite of the female Anopheles gambiae mosquito, affected an estimated 214 million people across the world last year. There is no malaria vaccine, and although the disease is curable in its early stages, treatment is costly and difficult to deliver in places where it is endemic, including Africa.

"All mosquitoes, including the one that transmits malaria, use their sense of smell to find a host for a blood meal," says Christopher Potter, a neuroscience professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. "Our goal is to let the mosquitoes tell us what smells they find repulsive and use those to keep them from biting us."

Each mosquito has three pairs of "noses" for sensing odors. One of these is the labella, two small regions that contain both neurons that pick up tastes and neurons for recognizing odorants.

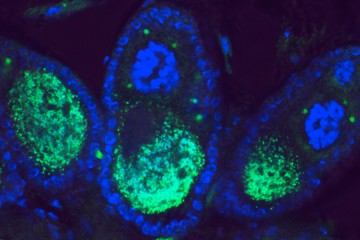

Using a powerful genetic technique—never before accomplished in mosquitoes, according to Potter—the scientists were able to make certain olfactory neurons in mosquitos "glow" green. The green glowing label was designed to appear specifically in neurons that receive complex odors through proteins called odorant receptors, or ORs.

The researchers were surprised to see that OR neurons from the labella went to the so-called subesophageal zone of the brain, which had never before been associated with the sense of smell in any fly or insect. In the past, this zone had only been linked to sense of taste.

"That finding suggests that perhaps mosquitoes don't just like our smell, but also our flavor," Potter says. "It's likely that the odorants coming off our skin are picked up by the labella and influence the preferred taste of our skin, especially when the mosquito is looking for a place to bite."

The findings offer researchers new possibilities for repelling mosquitoes, Potter says. A new type of repellant could target the labellar neurons and make mosquitoes turn away in disgust before sucking our blood. This would provide an extra layer of protection to repellants targeting mosquito antennas, which reduce the likelihood they get too close in the first place.

The genetic system Potter's team devised to generate the glowing neurons will make it easier for his and other laboratories to mix and match genetically altered mosquitoes to generate new traits, he says. His group has already created a strain of An. Gambiae mosquitoes whose OR neurons glow green upon activation. Scientists can therefore see which neurons light up in response to a specific smell.

"Using this method, we hope to find an odorant that is safe and pleasant-smelling for us but strongly repellant to mosquitoes at very low concentrations," Potter says.

Read more from Hopkins MedicinePosted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged malaria, mosquitoes