Researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and two other schools published a study today that offers compelling evidence of a biological link between Zika virus and microcephaly and could give scientists key insights into how to treat the virus.

The study does not establish a definitive causal link, experts note, but it does connect Zika virus to cell abnormalities. Though microcephaly can be caused by a number of genetic, viral, and environmental factors, the abnormal cellular behavior seen in the study was produced solely by the Zika virus, researchers say.

"I think the study is going to be incredibly important to the understanding of how microcephaly develops," says Jeanne Sheffield, director of the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at JHU's School of Medicine who testified earlier this week before a Congressional panel examining the U.S. public health response to Zika virus. "Not only does it give us more data that there is a link, but it's also giving us data that we didn't have about what is going on at the cellular level. That is huge from our standpoint as we try to figure out why babies are developing microcephaly."

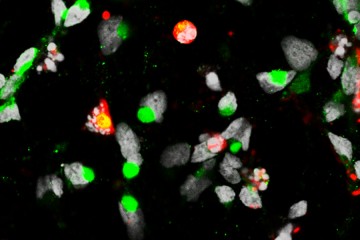

In the study—conducted by researchers at Johns Hopkins, Florida State, and Emory universities—cortical neural progenitor cells, which form the brain's outer layer, were exposed to Zika virus. Three days later, 90 percent of those cells had been hijacked to produce copies of the virus. Many of the infected cells died, and surviving cells were unable to divide and make new cells effectively.

The research team will continue researching the effects of Zika on the cortical neural progenitors and how the cell disruption demonstrated in the study may affect a growing brain. Sheffield noted that the study could aid scientists' understanding of how Zika infections occurring at different stages of pregnancy could produce different fetal outcomes.

"With a fetus, you're talking about development: the nervous system is developing, brain structures are developing, especially early on in pregnancy," Sheffield says. "In an infection in late pregnancy … even though the brain structures may appear normal, that does not mean that there will not be long-term complications from Zika infection."

The new study adds to a growing body of evidence showing the ways in which Zika virus affects the central nervous system. A study published Monday in The Lancet explores evidence that the outbreak of Zika virus in French Polynesia led to an increase in Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune disease wherein the immune system attacks the central nervous system and in some cases causes paralysis. Earlier today, Nature reported that researchers have found Colombia's first cases of birth defects linked to the Zika virus, the beginning of what experts expect will be a wave of Zika-related birth defects in the country.

Thomas Quinn, director of JHU's Center for Global Health, says he is impressed by how quickly scientists have responded to what the World Health Organization has labeled a public health emergency.

"I'm pleased to see people from around the country working together," he says. "This type of collaborative research, plus the clinical work that was presented at the Zika symposium, plus epidemiological studies, the neurology studies, the OB-GYN studies—that is what global health is all about. It is the multidisciplinary approach to tackling a global problem. And Zika is now, without a doubt, a global health problem."

Posted in Health

Tagged epidemiology, zika virus