The annual delivery of influenza vaccine to the American public is hardly a straight shot from federal health officials to vaccine manufacturers to physicians to patients. A recurring and vexing part of the process is a supply-chain hitch that can leave patients waiting for flu shots even when the supply of the medicine is abundant.

Image caption: Tinglong Dai

A recent study from Johns Hopkins University offers a potential remedy by proposing a new kind of contract between vaccine manufacturers and the retailers—such as physicians' offices and pharmacies—that purchase and dispense the shots to patients. The researchers recommend an approach that they say would engender a prompt and steady flow of vaccine from producers to dispensers, primarily through a pledge by the vaccine makers to buy back all unused doses and pay rebates for late deliveries.

Examining more than 20 years of vaccine-purchasing practices at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Tinglong Dai, an assistant professor at JHU's Carey Business School, and two co-authors have written what they claim is the first paper about the commercial side of the flu vaccine supply chain. Previous research has looked at the interplay between the government and manufacturers. Dai and his colleagues—Soo-Haeng Cho of Carnegie Mellon University and Fuqiang Zhang of Washington University in St. Louis—say their study breaks new ground by considering the role of retailers as well.

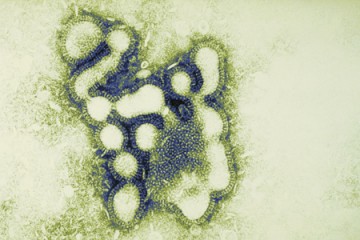

The vaccine process begins several months before the first patients receive their shot, explains Dai, the lead author of the study. By the beginning of January, manufacturers already are looking ahead to next fall's flu season and starting production of a vaccine to match the expected strains. Their aim is to make a large quantity that will be ready to sell to retailers by vaccination season, which usually runs from late September to mid-November.

At best, however, the manufacturers make only an educated guess when they try to get a jump on a production regimen that routinely lasts about six months. The federal Food and Drug Administration, with input from the World Health Organization, selects the targeted strains of the coming flu season. But the agency doesn't finalize them until February or March. If manufacturers have guessed wrong on any of the three or four chosen strains, they must restart that part of production.

Retailers, aware of the manufacturers' risk, anticipate potential delay in shipments and may commit to smaller orders than are ideal. They want to avoid requesting a large supply that could arrive in late fall, when public demand will be down, and then being left with unused doses. The manufacturers, knowing that retailers will follow this cautious strategy, are thus reluctant to produce a large amount before the FDA's final announcement.

Dai describes this dance between the manufacturers and retailers as a classic example of a negative feedback loop. The result can be a shortage during the period of peak demand, as happened in 2014.

"It's a coordination problem," Dai said. "The parties involved are not behaving in the optimal way—not because they're being selfish but because they're trying to anticipate the other party's moves."

As the researchers show, manufacturers have experimented in recent years with various types of contracts to promote both production and purchases. For example, one company offered full credits to retailers on returns of up to 25 percent of unused doses shipped before Nov. 15, then up to 50 percent of unused doses shipped after that date. A subsequent contract by the same manufacturer bumped that date up to Oct. 15. Another company ruled out returns or rebates for late deliveries one year, then extended a 10 percent rebate for returns of post-Sept. 30 shipments the next year, and then went back to no returns or rebates the following year. Small wonder, Dai says, that the process is riddled with uncertainty and frustration.

Because the Buyback and Late Rebate (BLR) solution put forth by Dai and his colleagues is based on familiar aspects of industry practice and supply-chain theory, they say it could be comfortably adopted by manufacturers and retailers alike. As Dai explains, buybacks occur in businesses involving time-sensitive products, such as newspapers, holiday goods, and fashion apparel. And while late rebates happen less frequently, they have been used in Walmart's dealings with its overseas suppliers as well as in the vaccine business. However, the researchers say they know of no other industry that employs the combined BLR approach.

"BLR is similar to those other practices, but with a slight twist," Dai said. "What we propose is that the retailer would not be limited in his ability to return any unused product. He can return 100 percent of it, not just a specified fraction of it, and instead of the usual full refund, he would get a partial one. In addition, he would receive a partial rebate on all late deliveries."

Dai says he and his colleagues believe that the combination of 100-percent buyback and rebates on late shipments would motivate retailers to commit to larger orders, which in turn would lead manufacturers to commit to greater and more prompt production. The negative feedback loop would be broken, and a steady, reliable flow of vaccine would be available, to the benefit of manufacturers, retailers, and patients.