Though her new book about the lowest depths of American poverty doesn't focus on Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University social scientist Kathryn Edin says it's "very much a Baltimore story."

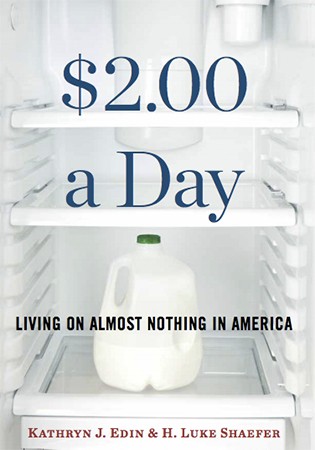

The book, $2.00 A Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America, was inspired in part by a group of young adults who grew up in Baltimore's high-rise public housing projects, Edin said at a reading Monday night at Mason Hall on JHU's Homewood campus.

Edin and her research team from Harvard had first visited the families in the 1990s, and returned in 2010, "post–welfare reform," she said, to check in on how the youngest of them were faring at the brink of adulthood. Among them was 19-year-old Ashley, who lived with her newborn and four family members in a virtually unfurnished apartment in the LaTrobe Homes along Madison Street. Edin sat on the floor to conduct her interview. She saw that the home contained no food and no baby formula. Ashley was unkempt, visibly depressed.

Asked how the household made ends meet, Ashley revealed that no one in the family had a job, and they were also not receiving welfare or food stamps.

A succession of these interviews stirred Edin and her team to question the "unintended hidden consequences" of the landmark 1996 welfare reform act. It seemed that a sector of poor people with neither income nor public assistance "had risen up under our noses," she said.

Video: Kathy Edin discusses her book at JHU's Mason Hall

Edin brought in "brilliant young data nerd" H. Luke Shaefer to look more closely at the phenomenon. The University of Michigan researcher examined Census data to determine what slice of the American poor fell below the World Bank's standard of global poverty for the developing world—$2 per person, per day.

"His results stunned us both," said Edin, who is now a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor at Johns Hopkins. She and Shaefer co-authored the new book.

The researchers found that in early 2011, 1.5 million households—including 3 million children—were surviving on no more than $2 per person per day of any given month. They also discovered that the $2-a-day poverty level had been on the rise, more than doubling, since the 1996 welfare reform under President Bill Clinton that created the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.

Edin and Shaefer's book goes beneath the surface of those statistics by profiling the day-to-day lives of eight families who live below this poverty threshold. They did their research in Chicago; Cleveland; Johnson City, Tennessee; and a collection of rural hamlets in the Mississippi Delta.

At Monday night's reading, Edin shared the story of a family in Johnson City. With the husband, Travis, laid off from McDonald's, their sole source of income was wife Jessica's biweekly donations of her own plasma, at $30 a pop. Three months behind rent, the couple and their two young daughters lived in constant fear of eviction.

The title of the book's first chapter, and its boldest pronouncement, is: "Welfare is Dead." While America's old welfare program served more than 14.2 million people in 1994, by 2012 there were only 4.4 million left on the rolls.

"Welfare's virtual extinction has gone all but unnoticed by the American public and the press," Edin and Shaefer write. At the same time, other types of government aid for the poor—such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)—have expanded. The problem is those benefits largely apply to those with jobs while failing to reach the unemployed and underemployed who need them most.

Part of the reason for this, Edin said, is both a "stronger sense of stigma" attached to welfare and "a desire for quick transition to employment." Many who might qualify for TANF don't even bother pursuing it. In addition, she said, many parents no longer justify prioritizing childcare while holding out for solid jobs.

Edin said the findings left the researchers "tempted to write a bigger story" about "the changing nature of work" in America, where part-time employment, on-call jobs, unsteady hours, and wage theft are commonplace.

Though she's researched low-income communities for years, Edin said her work for $2.00 a Day "really took a toll on me," and it was "hard to know if Americans would really respond with compassion, or fear and wanting to turn away." But since the book came out in September, she said, "we've really been encouraged by the degree of compassion" in people's responses.

Edin's Nov. 9 reading, sponsored by the Friends of the Johns Hopkins University Libraries, was part of an ongoing book tour.

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged sociology, poverty, kathryn edin, welfare