Public health icon D.A. Henderson stands over a display case that, in his estimation, holds one of the greatest innovations of the past 100 years—the bifurcated needle. Quite frankly, it doesn't look like much. It's a 2.5-inch-long narrow steel rod with two prongs at the end, like a sewing needle that's been clipped at the eye.

But the beauty, Henderson says, lies in its utility.

The needle could hold a dose of reconstituted smallpox vaccine in its prongs and easily puncture a person's skin to the ideal depth for delivery (and at $5 per 1,000 needles, they were quite a value). Through its use, up to 100 successful vaccinations could be given from just one small vial of the reconstituted vaccine.

Wyeth Laboratories developed the needle as a cost-effective alternative to the U.S. Army's jet injector, a clever but somewhat clunky vaccinating device (imagine an inoculating gun attached to a portable generator) that required its own mechanic. In a triumph of David over Goliath, the tiny needle—not the snazzy jet gun—would become the primary field instrument for the World Health Organization's Global Smallpox Eradication Program, an unprecedented immunization campaign from 1966 to 1977 that was spearheaded by Henderson. During the campaign, the bifurcated needle aided in the delivery of more than 200 million smallpox vaccines per year.

"It was a miracle for us," says Henderson, who at age 86 still possesses a commanding presence, buoyed by a resonant Midwestern accent and a tall, barrel-chested frame. "Without that needle, the eradication campaign would have taken that much longer, and it's what allowed the campaign to succeed as spectacularly as it did."

The bifurcated needle, a jet injector, vaccine vials, and dozens of other artifacts and documents detailing man's victorious battle against smallpox, a once feared and ruthless disease, are currently on display in the new second-floor exhibition gallery of the Welch Library building on Johns Hopkins University's East Baltimore campus. The exhibition, the first in the new space, is titled Smallpox: Vaccination/Eradication. It displays highlights from the Institute of the History of Medicine's Edward Jenner Collection, named for the doctor who promoted the use of cowpox vaccination to provide immunity to smallpox in 1798, and the recently donated D. A. Henderson Collection of material relating to the WHO Smallpox Eradication Program.

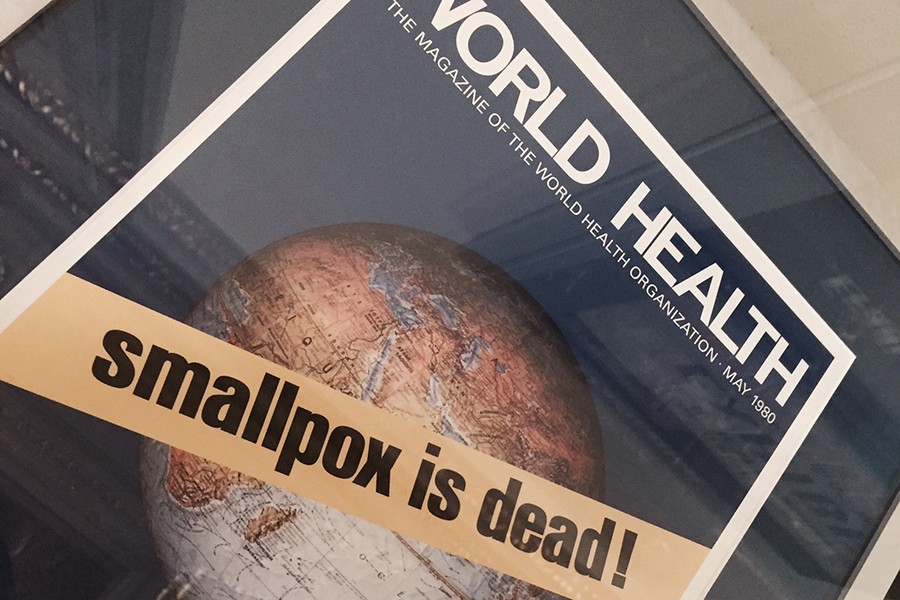

Henderson, former dean of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (and your author's generous tour guide through the exhibit), headed the WHO campaign that resulted in the declaration of the worldwide eradication of smallpox in 1980.

Essentially, Smallpox: Vaccination/Eradication honors two men, separated by two centuries, who persevered in a fight despite long odds and a sometimes resistant public.

Their shared nemesis dates to the time of the pharaohs in Egypt, and possibly further back. Once known as pox or the red plague, smallpox is an infectious disease that could disfigure and kill those it infected. It begins with flu-like symptoms and, days later, red spots appear, first on the face, then spreading to the arms, legs, and torso (and sometimes inside the mouth). Many of the lesions later turn into puss-filled blisters that leave pitted scars. Nearly a third of cases proved fatal, and more than half of those infected were scarred for life. Some were left blind. There was no treatment.

"Smallpox is one of the most feared diseases mankind has ever known," Henderson says. "The plague went through Europe and was certainly destructive, but smallpox was a more constant disease throughout history."

By the 18th century, an estimated 400,000 Europeans died annually from the disease, and it was a cause of a third of all blindness.

Then along came Edward Jenner, an English physician who had learned of a possible path to immunity—cowpox. Unlike smallpox, cowpox is a minor disease in humans, akin to catching a cold. Jenner and others found that if you inoculated a cowpox pustule into a human, he or she would be immune to smallpox. Jenner famously tested this theory on an 8-year-old boy with matter taken from a pustule on the arm of Sarah Nelmes, a milkmaid who had cowpox (the exhibit includes a lock of hair taken from Sarah's cow, Blossom). On July 1, 1796, Jenner inoculated the boy with smallpox, but he never got sick. The antibodies resulting from the cowpox infection made him immune. Cowpox matter became the first vaccine in mankind's history. In fact, the word vaccine comes from the Latin word for cow, vacca.

Jenner promoted his findings vigorously. He published, at his own expense, a slender volume titled An Inquiry Into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae vaccinae that detailed 23 cases in which cowpox had conferred lasting immunity to smallpox, and he distributed it to anyone who mattered. During the next three years, the practice of vaccination quickly spread throughout Europe.

"Jenner got everyone excited that we can prevent this disease," Henderson says. "This is the first time that humankind could say that about any disease. By the start of the 20th century, most developed countries didn't have chronic smallpox, and that all starts with Jenner."

Not everyone got in line for vaccinations, however.

Some religious groups didn't appreciate the medical marvel. They felt that a higher power or powers had chosen to beget smallpox on man, and to interfere would be sacrilege.

"The other major problem was that here was the first time we are taking an animal product and inoculating it into humans. Some were very hostile to that, too," Henderson says, pointing to a early 19th-century illustration that shows cow parts growing out of people who were vaccinated.

Also see: A cow head will not erupt from your body if you get a smallpox vaccine (NPR)

Despite the cowpox vaccine's success in Europe, the practice did not spread to the developing world. By the mid 1960s, there were an estimated 10 million cases of smallpox worldwide, most confined to South America, sub-Saharan Africa, India, Burma, Bangladesh, and Indonesia.

At the time, Henderson worked for the Epidemic Intelligence Service of the Communicable Disease Center (now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), where he created a Smallpox Surveillance Unit to deal with imports of the disease to the United States. In 1967, he was dispatched to Geneva to lead the WHO eradication campaign. His first main contribution was to introduce the bifurcated needle and have it replace the rotary lances, which were a less effective and far more painful means of vaccine delivery.

Within three years, Henderson and his team had most of the world using the bifurcated needle. The team also persuaded health centers around the world to do a better job of reporting cases and made sure health care staff were vaccinated.

"Smallpox wants to spread in a continuous chain," he says. "So we wanted to vaccinate the people most likely to be in contact with a smallpox patient, effectively cutting one of the chains. It's what we called ring vaccination."

By 1971, large swaths of Africa were free of smallpox, and the number of worldwide cases had dropped to 52,807. Only 12 countries recorded endemic cases.

"We thought this was unbelievable. It just might work," says Henderson, displaying an enthusiasm not withered by the intervening four decades.

By 1973, the only two smallpox strongholds left were Ethiopia and India. In India, the roadblocks were religion and an inability to effectively introduce the bifurcated needle, as the government still advocated use of the rotary lancet.

"India was a big problem, a real struggle for us," Henderson says. "For one, people in India had a better ability to move around the country and over vast distances. They had more roads, railroads. By the time we learned of a case, that person might go into the city to infect others. It was going faster than we could keep up."

The solution? Investigate every Indian village in a 10-day period, or at least try. To do this, the WHO team enlisted a small volunteer army of Indian civilians who went door-to-door. "This is what allowed us to turn the corner in India," Henderson says.

In July 1975, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi gave a speech in New Delhi in which she announced that the nation was smallpox-free for the first time in its written history.

"At this point, it really hit me," Henderson says, recalling the day. "I thought, my goodness, this is really going to happen. We had long used the term 'target zero,' and now we all felt it was within our reach."

Ethiopia was the next to fall, as the team eventually overcame the obstacles of civil wars, floods, famine, a poor road system, and a reluctant population. The WHO campaign ultimately paid Ethiopian civilians to become vaccinators and used helicopters to reach the country's most remote regions. The last case of smallpox ever recorded was in October 1977, in neighboring Somalia.

The exhibition features a carved wooden statue that represents the world's last case of smallpox, a man looking up at the heavens for a WHO helicopter that is coming in to land.

"[The campaign] was a remarkable experience, and something I'm very proud to have been part of," Henderson says. "I've held on to all my mementos and artifacts from this time because I wanted to preserve what happened, and [the campaign's] place in history."

You can come see them for yourself. The exhibition will be open until late February.

"Smallpox: Vaccination/Eradication" can be viewed in the exhibition gallery on the second floor of the Welch Library building on Johns Hopkins University's East Baltimore campus. The building is open Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. and on Saturday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. The exhibition is free and open to the public.

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged epidemiology, welch medical library, vaccines, infectious disease, smallpox