The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled Thursday that the Food and Drug Administration is not required to hold hearings that could end the use of penicillin and tetracyclines in animal feed.

The court's split decision is a tremendous disappointment and a setback for public health, said Keeve Nachman, a food production and public health researcher at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future and a faculty member at the Bloomberg School of Public Health.

"Penicillin and tetracyclines are necessary and commonly prescribed antibiotics used to treat a variety of infections in people," said Nachman, who directs the center's Food Production and Public Health program. "If they lose their effectiveness, many infections that used to be easily treatable will become far more dangerous and costly to treat."

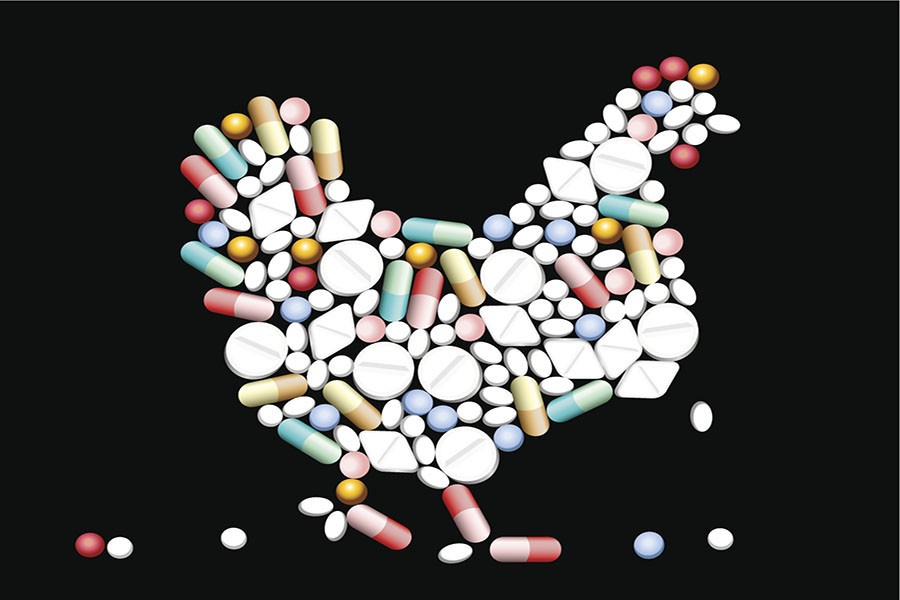

Experts say there is overwhelming scientific evidence linking the continued use of antibiotics in food animals to rising antibiotic resistance in humans. If the FDA were required to hold hearings on the issue, drug manufacturers would have to prove that giving antibiotics to food animals for nonmedicinal purposes is safe.

Studies show that the practice of feeding antibiotics to animals for purposes other than treating or controlling disease unnecessarily contributes to the development of bacteria that are resistant to drugs, such as penicillin and tetratcyclines, used for treating common infections in humans.

More, from The Wall Street Journal:

In its 2-to-1 decision, the appeals court wrote Congress "has not required the FDA to hold hearings whenever FDA officials have scientific concerns about the safety of animal drug usage [and] that the FDA retains the discretion to institute or terminate proceedings to withdraw approval of animal drugs…"

And in response to arguments that the FDA failed to act in the face of scientific evidence, the court added that "whether long-running inaction by the agency was politically inspired foot dragging or wise caution in developing a cost-effective approach [to addressing the problem], it was for the agency, and not the courts, to determine how to best proceed."

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged center for a livable future, food safety, agriculture, antibiotics