A relic of times past, Maryland's Bloede Dam—the world's first self-contained, underwater hydroelectric dam—stretches across the Patapsco River in what is now Patapsco State Park. Built in 1907, this dam, a hollow-core concrete structure 230 feet across and more than 30 feet tall, provided power to nearby homes and businesses in the Patapsco Valley, a hotbed of industrial innovation in the 1930s.

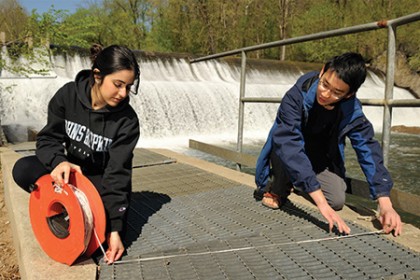

Image caption: Seniors Laila Khaled Nasr and Peter Bai take measurements along a fish ladder installed next to the Bloede Dam in the early 1990s.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Abandoned in 1931, the dam now is the focus of an environmental dilemma. The structure stands between migratory fish, such as herring and Hickory shad, and more than 60 miles of free-flowing river. But it also is a historical landmark, and its removal raises concerns about releasing stored sediments into the river and, ultimately, the Chesapeake Bay. This spring, Johns Hopkins students in the Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering's Senior Design Class were tasked with developing solutions to the environmental stalemate.

The challenge: to solve the fish-passage problem while accounting for issues of water quality, public safety, integrity of a nearby sewer line, historical and cultural values, and cost and feasibility.

Read more from Johns Hopkins Engineering magazinePosted in Science+Technology, Student Life