Novelist Rick Moody will be the featured reader when the The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review debuts its Rue de Fleurus Salon and Reading Series June 27 in Washington, D.C. The Eckleburg Review is a nonprofit literary and arts magazine housed in the Johns Hopkins Master of Arts in Writing Program, where Moody will lead a craft session with fiction workshop students prior to his appearance. He's joined by novelist and writing program faculty member Richard Peabody; visual artists Chas Schroeder, Annie Terrazzo, and Kareem Rizk; writer, recent program graduate, and Seltzer zine editor Peter Cardamone; program alumnus Dana Little; and Rae Bryant, Eckleburg's founding editor. The event is takes place at 7:30 p.m. at the Foundry Gallery and is free and open to the public—a Facebook RSVP is requested.

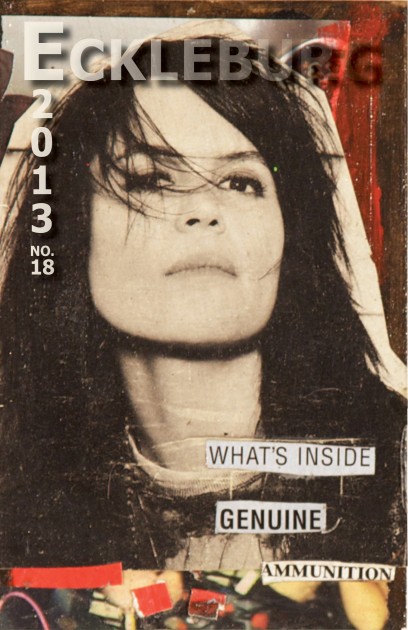

Image credit: "The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review' cover art by Chas Schroeder

The Rue de Fleurus, presumably named after the street on which Gertrude Stein lived in Paris, is a throwback to the salon as intellectual gathering and art exhibition. "We really wanted to have a salon series that [included] not only reading but also art and intermedia," Bryant says. She hopes to be able to schedule at least three salons per year (one each in the fall, spring, and summer semesters) and move its location between Baltimore, Washington, and maybe New York. "We feel very strongly that music and intermedia, artwork, the text, the book—everything comes so beautifully together, so we wanted to do something along these lines."

The salon is the latest milestone for Eckleburg Review, which made its debut in spring 2012. Moody judged its inaugural fiction contest, with Jill Birdsall winning the first Gertrude Stein Award for her short story "Salvage." Birdsall's story, along with second-place winner Michael Shum's "In Defense of the Body" and third-place finisher Bird Marathe's "Hello My Friend," will appear in the 2013 print edition of the Eckleburg Review coming out this summer, which also includes contributions from Moody, poet Moira Egan, author and former Writing Seminars Professor Stephen Dixon, essayist and short-story writer Steve Almond, novelist Vallie Lynn Watson, and more.

The magazine grew out of the similarly broad-minded Moon Milk Review, which Bryant started in February 2010 as a graduate student in the writing program. She graduated in 2011, and during the summer of 2012, "the program was looking to bring on a literary presence, and [the Moon Milk Review] was looking to make some transitions. It was just a really good fit at the time," Bryant says of the partnership. "So we decided to reconstitute the Moon Milk Review. I liked the idea of taking on a [F. Scott] Fitzgerald allusion of some sort because of the location, being the Baltimore/D.C. metro area. So when we transitioned the Moon Milk Review to being housed in the program, I changed the name."

Fans of The Great Gatsby will recognize Doctor T.J. Eckleburg from the faded roadside billboard Nick Carraway and his fellow revelers pass anytime they drive from Long Island into Manhattan:

The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic—their irises are one yard high. They look out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a nonexistent nose. Evidently some wild wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness, or forgot them and moved away. But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days, under sun and rain, brood on over the solemn dumping ground.

In the novel, the billboard functions as an all-seeing reminder of the ephemerality of conventional American success, and it nicely complements the magazine's mission. Bryant created Moon Milk as a pan-arts magazine, and Eckleburg's volunteer editorial staff expands upon that broad vision with the magazine and its online content. The staff posts new content weekly if not daily, from new poetry and fiction to art and music in its Groove section, where, Bryant says, "we're trying to highlight not only sort of classic, classic alt music, a lot of punk, we like some of the classic rock, but we're also trying to highlight indie bands that are making the underground circuit right now but maybe not a lot of people know about."

It's an eclectic mix of engaging and emerging young artists and writers along with interviews and gritty, quick-hit items such as this YouTube clip of Charles Bukowski reading his poem "The Genius of the Crowd", a musically monotone screed against the quiet suffocation of conformity.

This diverse programming is a recognition of how literary magazines are accommodating the digital readership; it's also a reflection of Bryant's and the staff's sensibility. They're reaching out to literary audiences who appreciate Bukowski's sly brashness and underground rock, and the work the Eckleburg staff and contributors produce can be equally insurgent. Bryant's stories in her debut collection, The Indefinite State of Imaginary Morals, seem to emanate from a place of psychological intensity and inescapable desire, and she writes with a surgical carnality.

"We have that indie vibe to us, so we have that smaller, very dedicated crowd of alternative lit and art followers, which is great," Bryant says of Eckleburg's readership. "We want to run a new short story every Monday, a new poem every Wednesday, we are trying to put up a new exhibition of artwork or multimedia or intermedia every week as well. We're really looking to push the intellectually artistic edges. We don't shy away from that as I think a lot of literary and art journals do, especially if they're affiliated with a university."

At the same time, Bryant and the staff are very conscious of growing the magazine organically, not taking on more than they can handle in terms of management and budget. "Our motto from the beginning has been that we want to take strong, small steps," Bryant says of the magazine's business model. "I've seen so many fantastic, small independent journals and small presses come out of the gate with all of these different projects and they burn out within a year or two or three. We're looking to be sustainable because we really want our contributors to benefit from that sustainability. We want the writing program and the students to benefit from that sustainability, so we're really careful about not taking on too much too fast."

For the moment that means one print edition per year, one salon per semester, and one writing contest per annum. The 2014 Gertrude Stein Award is already [accepting submissions](http://thedoctortjeckleburgreview.com/the-gertrude-stein-award-in-fiction/], and the Eckleburg Review has scored another peerless writer to judge the contest: Cris Mazza, an author of such incendiary intelligence it's flabbergasting she's not more widely renowned. In the mid-1990s she coined the term "chick lit" to counter the assumption that women don't write experimental fiction, co-editing a pair of postfeminist writing collections. Of course, since then the term "chick lit," as Bryant points out, "ended up being mangled into the idea of high heels and getting the perfect man."

"We love her," Bryant says of Mazza. "She has such a fantastic, crisp language and she is very willing to go into some of the edgier topics. So we're really excited."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged literature, books