Harmony in the workplace is highly desirable, but what happens when some workers depend on biological brains, while others need computers to guide their behavior? With an eye toward enhanced safety and greater productivity, Johns Hopkins engineers have joined colleagues at four other universities in a project to create new ways for humans and robots to work together cooperatively.

The scientists say that although robotic technology has made enormous strides, more attention needs to be directed at developing cooperation between humans and robots. The researchers say the idea that independent machines can do all the work in a hospital or manufacturing plant with no help from humans remains a science-fiction pipe dream.

During the current rush toward automation, Gregory Hager wants to keep humans in the loop. Hager, chair of the computer science department at Johns Hopkins' Whiting School Engineering, is a co-principal investigator in the new four-year, $3.5-million human-robot interaction research project, funded by the National Science Foundation. He said modern robots can surpass humans in some procedures, but in other tasks, humans still hold the edge.

"When it comes to heavy-lifting, repetitive motions, and work that requires an absolutely steady hand, robots perform really well," he said, "but they have trouble tying knots without human help. Humans are better at handling flexible materials like string or cable. People also excel in drawing on experience and making decisions. Our goal is to figure out how people and robots can learn to work together to complete tasks that neither can do alone."

To achieve this goal, Hager's team at Johns Hopkins is collaborating with researchers at Stanford University; the University of California, Santa Cruz; the University of California, Berkeley; and the University of Washington. The project is part of a larger federal effort called the National Robotics Initiative, which is aimed at speeding up the development and use of robots that work more cooperatively with people.

In their grant application, the team members said their project would address a wide range of manipulation problems "that are repetitive, injury-causing or dangerous for humans to perform, yet are currently impossible to reliably achieve with purely autonomous robots. These problems generally require dexterity, complex perception, and complex physical interaction. We conjecture that many such problems can be reliably addressed with human-robot collaborative systems, where one or more humans provide needed perception and adaptability, working with one or more robot systems that provide speed, precision, accuracy, and dexterity."

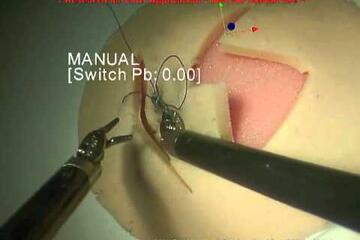

In particular, the researchers will focus on improving human-robot teamwork in two key areas: manufacturing procedures that involve a small number of objects, and medical tasks, including suturing and dissection. In these efforts, university team members plan to work with two companies that are seeking help from robotic technology experts.

One is a Kansas company that assembles wiring harnesses for commercial airplanes. This process involves a repetitive tying operation that is now carried out only by humans working manually. The current process results in uneven product quality and a risk of repetitive motion injuries. Finding a smooth way to weave robots into this process could reduce such problems, increase work efficiency and set an example for future manufacturing innovations, the researchers said.

The other focal point is robot-assisted surgery. The da Vinci surgical system uses robots that directly mimic the hand motions of a human operator sitting at a console a short distance from the patient. Currently, the human operator's role is limited by the technology, but the researchers intend to work with the maker of the da Vinci system to expand and improve the surgical tasks that can be performed by a human-robot partnership. Some of the work will focus on the use of two people seated at separate consoles, each manipulating different robotic arms in the operating room. The goal is to improve the speed, accuracy and precision of surgical tasks and allow the robot to handle more of the repetitive motions that can be a burden for humans.

In both the manufacturing and medical procedures, the researchers will also seek to enhance the verbal and tactile communication between the human and robot partners. "It's hard to get robots and people to work together, and it's even harder to get multiple people and multiple robots to work together," said Allison Okamura, a Stanford associate professor of mechanical engineering who is lead investigator on the NSF grant. "A main focus of our project is to get robots to understand what people are doing and be able to step in when necessary."

Along with Hager, the co-investigators on the project are Jacob Rosen at UC Santa Cruz; Blake Hannaford at the University of Washington; and Pieter Abbeel and Ken Goldberg of UC Berkeley.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged robotics