This article is part of the Provost's Project on Innovation series

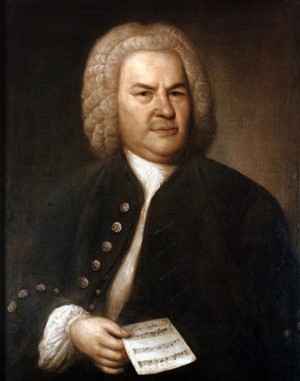

Image caption: German composer Johann Sebastian Bach

Image credit: Photos.com

Pity the town fathers of Leipzig in the Electorate of Saxony, circa 1723. They needed to hire a Kapellmeister, or director of music, for the town's churches—someone who would direct and manage the choirs, play the organ, and write music for Sunday services—and they knew just the man, or men. Multi-instrumentalist and leading composer of the day Georg Philipp Telemann would be ideal. But if he could not be convinced, certainly his contemporary, composer and harpsichordist Christoph Graupner, would do.

Unfortunately, neither would take the job. So a divided Leipzig Council less than enthusiastically went with their third choice, Johann Sebastian Bach, a composer and organist widely recognized for his musical gifts but also somewhat notorious for the difficulty of his music and the sometimes prickly relationship he had experienced with previous employers.

Like it or not, the town fathers of Leipzig had hired themselves an innovator.

Peabody Conservatory musicologist and cellist Andrew Talle, Ph.D., has spent a good part of the past decade grappling with the nature of Bach's creative mind. "Why is it that Bach so consistently challenged himself, his audience, and his players with his music?" he asks. "It wasn't because he was getting accolades from his institution. He had virtually no institutional support. In fact, the more we learn about his institution, the more remarkable it seems because he faced enormous opposition." In order to better understand the circumstances that influenced Bach's work, Talle found an apartment in Leipzig and has conducted research in the former East German city for a total of five years since 2000.

In the course of studying everything from the scandalously bawdy song sheets favored by university students in Bach's day to the daily lives of professional organists, Talle has come to conclude that a true musical innovator like Bach is, in the final analysis, compelled to answer a call from within. "Ultimately, people who do innovative work do it because they're driven compulsively to meet their own high standards. It's not because they're going to get prizes for it. They simply find personal fulfillment in achieving those goals," he says. "Bach is a clear example of someone who thrived on presenting huge challenges to himself. For 27 years in Leipzig, he was charged every week with getting a group of 12-to-18-year-old boys to sing in tune, with solid rhythm, taste, and expression, to say nothing of trying to prevent them from stealing silverware, throwing bread rolls, and worrying about the well-being of his own 20 children. If he had chosen to perform repertoire by other composers or written music that was easier to learn, he would have made his own life much easier. And the town council would have been just as happy; they wanted someone who wrote more accessible music, after all. But he couldn't bring himself to do that."

Talle himself has taken an innovative approach to understanding and interpreting the music of the man now widely regarded as one of the greatest composers in the history of Western music. He became fluent in German, permitting him to immerse himself in the life of Bach—searching libraries and archives for clues, any hidden details or insights that might reveal exactly how Bach's music was perceived by his contemporaries. He pays particular attention to the popular music of the day, something that Bach's music was most decidedly not.

Talle says that one reason for Bach's lack of popularity was the unique approach he employed in interpreting texts. As an example, he points to the divergent results when Bach and Graupner set the same poem to music. Graupner, ever a crowd-pleaser, created a palatable, easy work for voice, recorders, and strings that was sure to be enjoyed by the masses, a "pillow upon which the text rests," as Talle describes it. Bach took an entirely different approach, beginning with his choice of instrumentation. He decided to utilize the pipe organ, an instrument so powerful and complicated that Talle describes it as "the Large Hadron Collider of its time." Bach used the organ to create a confrontational and almost abrasive musical environment that demanded the full attention of the listener.

For Talle, the question is, why? "Bach consistently presented his audiences with puzzles. Why is it that this music seems to contradict the text? It's all about sorrow and sadness, but it sounds more mechanical than melancholy. Why doesn't he use the basses and cellos at all? The lowest instruments he uses are violas, which limit the range to the high end and give the piece a trapped, claustrophobic feeling. Your job as an audience member is to sit there and puzzle out why. He confronts you with a challenge and demands that you figure out what he is up to. Many musicians indulge their listeners, flattering their preconceptions. Bach chose instead to present his audience with riddles, which are ultimately very rewarding to solve. In this case, he wanted to evoke the pain of a mortal soul trapped in the mechanical, physical world, longing for peace with God. Bach was convinced that there was a world beyond the universe we know. In this respect, he has something in common with our colleague Adam Riess, who studies the parts of the universe that can only be perceived indirectly. Of course, Bach was thinking in terms of theology rather than physics, and his arguments were musical rather than empirical, but both were driven to innovate by a fascination with the unknowable."

Talle's own approach is unique in the attention he places on Bach's music as a direct reflection of the time and place in which the composer lived. "The central question for me is, How was Bach's music actually used in its time? What did people do with it? Because ultimately I'm much more interested in people than I am interested in music. If I'm innovating at all, it's in this way... I want to know what music people loved and hated in Bach's time, and why. To figure that out you need to know a lot about the rest of their lives."

Talle is in the middle of writing a book on his most recent research in Leipzig, a process that will be aided by his selection, in March 2011, as a Johns Hopkins Gilman Scholar. He says he sees Bach not as a timeless genius but as a real, living, breathing human with mortal concerns and priorities. It is by investigating the ordinary that Talle suggests we can begin to understand how the extraordinary emerged. "It's true, Bach wasn't trying to flatter the ears of his audience, but he also wanted his music to be liked. He just wanted it enjoyed on his terms," he says. "I think that's true of a lot of innovative musicians, and maybe innovative people in general, that they're not working independently of their audience. They just want a different kind of relationship with their audience than is typical."

It is exactly this same approach to the study of musicology that characterizes how Talle teaches his students at Peabody. When asked to describe what he wants his students to achieve musically, he pauses to think. "Be brave, I guess," he says eventually. "It seems mundane, but that's really all I can offer my students. Ultimately I can't tell them how they should play the music. All I can do is give them the knowledge and the confidence that they need, and encourage them to innovate by playing the music the way they would like to hear it."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged music