Jed Fahey, a nutritional biochemist at the School of Medicine, first tasted cooked moringa in a small Ghanaian village in late 2006. He recalls crushed-up moringa leaves—a spicy, astringent, horseradish-tasting green—tossed into a soup that contained mystery meat, which he later found out was rat. "I have to admit, it tasted good," says Fahey. "I didn't have the heart to tell them I was a vegetarian."

Image credit: Photograph by Chen Hualin

Fahey had traveled to Ghana not just to eat local cuisine but to speak at an international workshop on moringa, a tropical tree hailed for its healing powers and as a powerful weapon to prevent malnutrition in dry and remote regions.

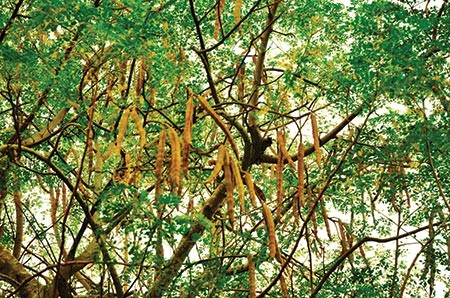

Known worldwide by many names—"the drumstick tree," "mother's best friend," "the miracle tree," "the never die," and "ben oil tree"—Moringa oleifera, the most widely cultivated species of this genus, possesses an abundance of nutritional and medicinal properties, according to anecdotal evidence and a growing number of scientific studies. The tree's edible leaves alone pack a superpunch of protein, iron, potassium, calcium, nine essential amino acids, and vitamins A, B, and C. Moringa's seedpods, shaped like a 2-foot-long piece of asparagus, contain seeds rich in protein and omega-3 fatty acids. But moringa's utility may be more than just as a dietary dynamo. Mature moringa seeds can be pressed into vegetable oil, suitable for both cooking and as a machine lubricant. The powder from crushed seeds can be used to purify drinking water because proteins in the seeds make bacteria clump and fall to the bottom. Of particular note, the tree's leaves and seeds have been shown in lab and animal studies to have strong anti-inflammatory, cardio-protective, anti-asthmatic, antibiotic, and anti-diabetic properties owing to their phytochemicals that protect against cancer and even inhibit tumor spread.

Fahey first became aware of the tree's potential at a U.S. Department of Agriculture research station in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, in 1996, where a colleague shared a paper he'd just written on its utility. "We talked moringa all day, and I was hooked," he says. In 2005, after a decade studying its nutritional and pharmaceutical assets, Fahey authored a review of the compelling, but still incomplete, medical evidence on moringa for the online Trees for Life Journal. The oft-cited article made Fahey the go-to source on all things moringa and an in-demand speaker on the topic. Now he's written the sequel: This spring, Fahey will publish "Moringa oleifera: A review of the medicinal potential" in Acta Horticulturae, a journal of the International Society for Horticultural Science. The paper outlines the plethora of promising studies on moringa over the past decade.

While Fahey cautions that most of the scientific evidence to date is based on animal studies, he notes that a few preclinical investigations and some small clinical trials are underway. The new evidence, he says, shows preliminary support for many medicinal claims. Six studies conducted in India, for example, showed that moringa leaf extract reduced blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes. Half of the studies, however, did not include placebo control groups. These and other studies highlight the need, he says, for more rigorous scientific evidence and clinical trials in the Western medical tradition to separate claims from fact.

Currently, Fahey's lab is looking at the glucosinolates and isothiocyanates found in moringa. The plant has a chemical makeup similar to that of another plant Fahey investigates, broccoli sprouts, which have been shown in many studies to help prevent certain cancers and possibly ease classic behavioral symptoms in those with autism spectrum disorders. "I'm convinced that anti-cancer properties will ultimately be demonstrated in moringa, in an animal and then a human model," says Fahey, director of the Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Chemoprotection Center at the School of Medicine.

Since 2004, Fahey has collaborated on moringa research with Mark Olson, a professor of evolutionary biology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Fahey helped secure funding for Olson and his wife to establish a farm in the western Mexican coastal town of Agua Caliente Nueva, where they raise cultivars of moringa brought in from around the globe. One aim: to study how different moringa varieties perform under the same climate conditions, then compare them to their wild cousins. They've already found that some of the beneficial phytochemicals in the wild variety have been bred out of some cultivated moringa, likely for the sake of taste and ease of harvesting. Fahey and Olson hope to identify a breed of moringa that is easy to cultivate and palatable but still retains its full suite of nutritional and medicinal benefits. The optimal varieties, he says, can be shipped to labs around the world for clinical trials.

Moringa, not surprisingly, has been hailed as the latest and greatest superfood, or the new kale. It's already on the shelves at Whole Foods. But Fahey grimaces at the term superfood. He believes moringa's true value is much more than an ingredient in a smoothie, and he has ethical issues with the carbon footprint associated with shipping moringa from forests in Africa and Asia to U.S. cities. He and other biochemists believe that moringa could help fight famine and malnutrition, and become a staple food source in hot, dry regions that will likely only become hotter and drier in the coming decades owing to climate change. "Those who could benefit most from its use are in the poorer regions of the dryland tropics where it's actually grown," he says. "That's where the plant could be a lifesaver."

Posted in Health

Tagged agriculture, moringa, superfoods, horticulture