Downstairs from the stage at the Merrick Barn, the most prominent actor on the Johns Hopkins Homewood campus tries to impart a hard-learned lesson, one he has absorbed over six decades in the limelight: Actors don't control the characters they portray. For all their preparation and the thespian bravado it allegedly inspires, there's a seat-of-the-pants element to treading the boards that keeps the vital player on edge, uncertain but electric. That composed, confident stage face? It's all an act.

To drive home the point, the professor leads his students, 11 undergrads who revel in theater but major in something else, in a game in which each adds one word to a story that emerges quickly around the circle they sit in. They are not allowed to ruminate. The tale of the moment, one that involves a girl going to a mall, temporarily comes to a halt when a student doesn't blurt out the next word fast enough. Where is the zap of voltage the actor is looking for?

"Do not plan!" the professor good-naturedly tells the student. "That took too long, Ellie. You'll destroy yourself by planning. Just listen—and answer quickly." He aims to hone their budding actors' instincts, to have them add something daring and extemporaneous only when they really feel it, to have new lines emerge organically. "You have to learn to forget"—he tells them as their narrative slowly unspools around the room, noting the paradox of memorizing for the stage—"so that a role or a line is fresh every time."

John Astin—that professor—has spent a lifetime striving for those transcendent moments. In a career that has included Broadway, film, and television—most famously, his three-year turn in the 1960s as Gomez, the not-quite-unhinged patriarch of The Addams Family—the actor has portrayed characters high and low, broadly comedic and darkly tragic, bringing a brash energy and courageous intensity to each of them.

He's embraced the same shoot-for-the-moon approach for his latest role: reviver of the theater program at Johns Hopkins, his alma mater. When Astin, A&S '52, returned to campus in 2001 ("It was the day the Ravens won the Super Bowl," he marvels) at the tender age of 70, the campus's stage-scape was ripe for the taking—if only because Johns Hopkins had become a wasteland for drama, a Waiting for Godot of uncertainty (to name-drop one of Astin's favorite plays). Theater at Johns Hopkins, part of a department called Writing, Speech, and Drama during Astin's undergrad years, had petered out by the late 1970s. For a few decades following, undergrads would still put on shows, but they were do-it-yourself productions. "They might have learned about running an organization, but there were a lot of limitations otherwise," Astin says—such as a lack of courses, one-on-one coaching, and a guiding hand.

Since his arrival, Astin has gone from leading a class during one semester each year to teaching as many as eight classes annually across the entire academic calendar. He has moved to Baltimore year-round, raised money for the once-moribund department, reestablished a theater minor, hired faculty, and grown the program from an initial batch of 54 curious students to 140.

But there's one bit of transcendence, one implicit—as he sees it—plot point that has yet to play out: the return of the theater major. "About a quarter of our students are theater minors, but most of the people who study theater here say they want the major," says Astin, who now serves as a visiting professor in the Writing Seminars, which houses the drama and production courses. "It's a question they ask frequently. Some students already treat it like a major, and then build another major around their theater studies."

Many of Astin's students have followed in his footsteps, becoming regularly paid actors in New York (as Astin did right after graduating), Los Angeles, and even Bollywood. So, why worry about whether students graduate with a degree in theater or not? "It has more to do with attracting a broader cross section of students to Hopkins and offering them an aspect of culture they couldn't otherwise find here," he says. "In those regards, a theater major will have a great benefit for the university."

His cultural rescue effort has been the subject of plaudits on campus, including from university President Ron Daniels and Katherine Newman, dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. When the university renamed the stage in the Merrick Barn the John Astin Theatre last December, Astin's old friend, Edward Asner, came for the ceremony. He heard noises-off echoes of his old friend. "I talked with people who told me they were at Johns Hopkins because of John, that he'd given Hopkins something it hasn't had and that it desperately needs," says Asner, who met Astin a half-century ago when the two were playing off-Broadway in Bertolt Brecht's The Threepenny Opera. "He's tempering the harshness of the sciences with the humanity of the dramatic arts."

That's not exactly what Astin had in mind as a youngster in Baltimore, where he was born, or in and around Washington, D.C., where he grew up. Just as performing a role well allows for a surprise or two, Astin's path to Johns Hopkins, then back to it, was sinuous, unpredictable. A teenage math whiz whose father, Allen Varley Astin, was a postdoctoral physics fellow at Johns Hopkins during the Great Depression before eventually becoming chief at what was then called the National Bureau of Standards (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology), John Astin planned to follow in his dad's footsteps. It was at Washington & Jefferson College, in western Pennsylvania, where the footlights first intervened.

Astin had received a scholarship to study mathematics, and he wasn't about to dally in the arts and letters. Once humiliated by a high school English teacher, who responded to his misreading of Moby-Dick by calling him a cretin—"I had characterized it as a fine adventure but thought at times it was like one long plug for the whaling industry," he says with a shake of the head—Astin was hardly game for studying humanities: "I was devastated by this. I had so much rage. I vowed never to take English again."

He met the teacher of freshman English "and told him I was only interested in the hard sciences," Astin says. "He said he'd let me off the hook but asked me if he could give me something to look at." He gave Astin a copy of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, which reminded Astin of the timeless value of fiction. Eventually, the same professor and some students pulled Astin toward the stage. He had already been wowed by a production of Thornton Wilder's Our Town (one that included Wilder himself in the role of stage manager) he had seen as a freshman. "It reminded me of the magic of day-to-day life," he says.

Astin and another student put on an on-campus production of Noël Coward's Ways and Means, with the professor's blessing. It was nerve-racking. But he got used to it. "At first, I was just terrified," he recalls. "But it seemed to get more comfortable as things went on. I didn't plan on making a living out of it, but I became fascinated by the process. There was an aspect of enrichment, a feeling of intensified living to it." After the show's two scheduled performances, Astin returned to the darkened makeshift theater, walking through the whole play by himself, in an attempt to "recapture that feeling of wonder," he recalls.

As he continued to study math intently, the tenor of things at Washington & Jefferson began to change. It was the early 1950s, when the House Un-American Activities Committee was questioning the loyalty of academics and government officials in an attempt to root out alleged communists. The college followed suit, grilling its educators and chasing many away. His professor friend left the school. Devastated, Astin soon did the same. He opted to transfer to Johns Hopkins because it was close enough to the family's Bethesda home "and they had this killer math department," he says.

That's when the biggest plot twist crept up on him. The acting bug bit. Hard.

Despite a determination to study math, Astin, to the consternation of his father, found himself taking acting parts around Baltimore. Many of them. He ignored his physics labs and ditched his French classes. His lack of attention to academic detail earned him a carpet call from G. Wilson Shaffer, then dean of the university. To Astin's surprise, the dean suggested he apply for a scholarship, even though Astin, saddled at the time with incomplete assignments, didn't think he qualified. Shaffer encouraged him anyway.

"The generosity of that man—I'm eternally grateful for what he did for me," Astin says, citing that experience as a factor in his loyalty to the school. "I was so moved by that that I poured myself into my studies. My attitude became, 'Give it to me and I'll learn it.' At one point, I was taking 27 credits."

He would also soon make a fateful choice, swapping his natural love for math for his burgeoning appreciation of theater, becoming a regular at Merrick and the stage, then called the Johns Hopkins Play Shop, that would one day bear his name.

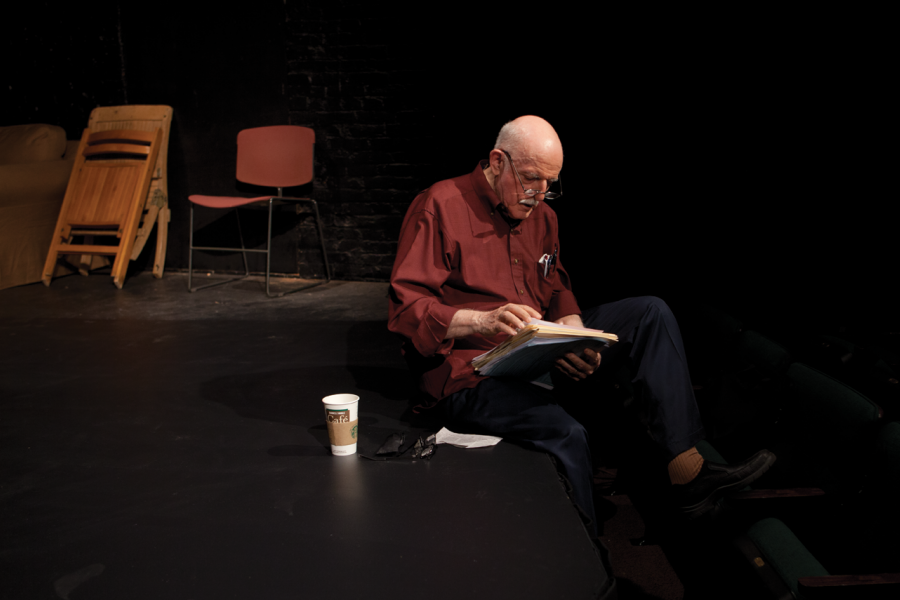

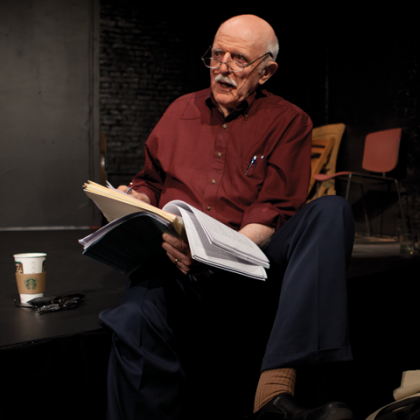

One warm late-winter morning, Astin teaches an elective course he created, called Contemporary Theatre and Film: An Insider's View, in the hall named after G. Wilson Shaffer. Now 82, with a fringe of white hair below and around his pate and the ever-present (though now ash-colored) mustache, Astin maintains an easy rapport with students, particularly those who place the stage at the center of their academics. At Shaffer Hall, the 35 kids in attendance—some rocking back in chairs, others texting or checking their messages, all from a variety of majors and schools—provide more of a challenge. He keeps things moving, tossing out some deep background on theatrical conventions.

Image credit: Christian Witkin

Astin starts class with some references to the bare-bones staging and gestures in Waiting for Godot, and then lurches backward into the tale of how Thespis and the ancient Greeks created first-person acting. (Prior to that, plays were written and acted in third person.) "Solon and other prominent Athenians thought that playing a character or singing a song that had 'I' in it was a form of lying," he says. "It was too close to Narcissus. Actors were thought to be unbalanced in those days. And that's an idea that has continued to the modern era. That's why in Hollywood—which was created not to make art but to make money, and it has needed to protect its image to do that—they included clauses in actors' contracts that rewarded them if they behaved and punished them if they didn't."

From there, Astin discusses the "humors" that the Greeks believed controlled emotions. Actors of the time used those humors as guides for the gestures they created onstage. In the 19th century, American and European thespians tied emotions to the gestures instituted by François Delsarte, Astin notes, just as those in the last century were inspired by the "psychological gestures" created by vaunted stage teacher Michael Chekhov. "If the emotion one is portraying isn't genuinely felt, then the gesture won't be honest—it won't work," he tells the students.

As he wraps things up, Astin ties the concept of the psychological gesture to his most famous role, as Gomez. The cartoons of Charles Addams, whose characterizations led to The Addams Family, gave him his cues, as did his acquaintance with Chas Addams himself. "His cartoons always had these tales of implied violence behind them, like when the family is on the roof getting ready to pour hot, molten metal on Christmas carolers," he says. "But there was never any violence actually carried out, so we laughed. I think what Addams was trying to do was shake us out of our boredom and routines so we could get in touch with this thrill of living." Astin applied that idea to Gomez, whose eyes and smile were as wide as his thrown-open arms. "He waved a cigar around and danced, and punctuated it all by an 'aha!'" he says, gliding seamlessly into character, to the delight of the students.

Those who have witnessed Astin at work at Johns Hopkins, or who have heard him speak about it, can't miss how he has embraced the idea of theater at the university. "He is as devoted to the mission of rebuilding the program as is humanly possible, probably because he loves it so much," says his son, the actor Sean Astin. "In my mind I have this image of my father, almost a spectral figure whose true age is a mystery, swooping around the [Merrick] Barn locking up late at night as he surveys the domain of his creative life. He considers restoring the drama program to a full major as the crowning achievement of his life."

But it's an act that has yet to play itself out. Bringing the major back depends upon the university's doing more to embrace the arts, including funding them. The Krieger School is pondering ways to ramp up its performing arts offerings—and not just theater. An arts task force created in 2010 recommended that the school make the arts a new point of emphasis.

As for theater, Krieger dean Katherine Newman and Astin agree that there should be enough money to hire someone to eventually replace him. "We have to plan for a post-Astin world, though we really don't want to think that way," Newman says. "He's a walking miracle. We owe a huge debt to him. Whatever we end up doing regarding theater, he'll be recognized as the founder of it."

For Astin, who says he wants to "make it to the century mark," the quest for the legitimacy and commitment that attend a full-fledged theater major means more than having his name attached to another physical feature of the university. He's waiting for that surprise, that crystallizing moment that shatters expectations. Treating theater with the respect he believes time has earned it would be that moment—both for him and for Johns Hopkins. "The university is so good at so many things it does," he says. "We generate all this knowledge, and it's not just about the medical school. What we need more of is wisdom, humanity. Hopkins is missing that chunk of humanity that it used to have. But we can bring it back."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged theater, john astin, drama, writing seminars